Yes, the Press Helps Start Wars

Donald Trump has again stirred the wrath of his critics by charging that the media can cause wars. His opponents immediately howled that he’d launched another salvo in his ongoing campaign to vilify journalists as the “enemy of the people.” They also ridiculed his contention as factually absurd. Fox News reporter Chris Wallace bluntly asked National Security Advisor John Bolton: “What wars have we caused?” Princeton University historian and CNN analyst Julian E. Zelizer epitomized the view that Trump’s charge is unfounded with a piece in The Atlantic titled, “The Press Doesn’t Cause Wars—Presidents Do.”

Zelizer and similar critics are technically correct, of course. Media outlets have no power to launch attacks on foreign countries or order U.S. troops into combat. But that view is much too narrow. As Zelizer himself admits, the new media have considerable ability to influence public opinion. Such a capacity to shape the overall narrative is not a trivial power. An irresponsible press can, and has, whipped up public sentiment in favor of military actions that subsequent evidence indicated were unnecessary and even immoral.

Two cases stand out: the Spanish-American War and the Iraq War. Historians have long recognized that jingoistic “yellow journalism,” epitomized by the newspaper chains owned by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, played a significant role in the former conflict. Months before the outbreak of the war, one of Hearst’s reporters wished to return home from Cuba because there was no sign of a worsening crisis. Hearst instructed him to stay, adding, “you furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.”

Hearst’s boast was hyperbolic, but the Hearst and Pulitzer papers did repeatedly hype the Spanish “threat” and beat the drums for war against Madrid. They featured stories that not only focused on but exaggerated the uglier features of Madrid’s treatment of its colonial subjects in Cuba. Those outlets also exploited the mysterious explosion that destroyed the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana’s harbor. To this day, the identity of the culprit is uncertain, but the yellow press exhibited no doubts whatever. According to their accounts, it was an outrageous attack on America by the villainous Spanish regime.

Such journalistic pressure was not the only factor that impelled William McKinley’s administration to push for a declaration of war against Spain or for Congress to approve that declaration. A rising generation of American imperialists wanted to emulate the European great powers and build a colonial empire. That underlying motive became evident when the first U.S. attack following the declaration of war came not in Cuba, but in the Philippines, Spain’s colony on the other side of the Pacific.

Nevertheless, it would be naïve to assume that the jingoist press did not play a significant role in causing the war against Spain. Indeed, the corrupt role of yellow journalism in creating public support for that conflict is not a particularly controversial proposition among historians.

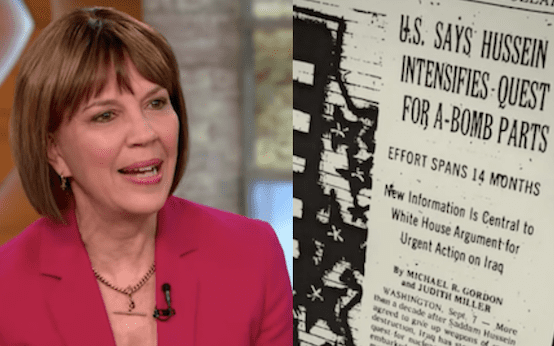

The role of an irresponsible press in shaping a pro-war narrative was even more evident in the prelude to the 2003 U.S. military intervention in Iraq. New York Times reporter Judith Miller and other prominent mainstream journalists were especially culpable in publicizing erroneous information about Saddam Hussein’s government regarding two emotionally charged issues. They uncritically circulated “evidence” from Iraqi defectors and George W. Bush’s administration that Iraq was in league with al-Qaeda and may well have had a role in the devastating 9/11 terrorist attacks. And they pushed the case that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction and was actively working on developing a nuclear arsenal.

Again, it would be too much to place all or even most of the blame for the disastrous Iraq war on gullible or ultra-hawkish journalists. The Bush administration seemed determined to oust Saddam, and it might have attempted to do so even without strong public support. But most of the media was staunchly pro-war, and that bias greatly skewed the narrative presented to the public. When highly respected journalistic institutions like The New York Times circulated story after story highlighting the alleged security threat that Saddam posed, and those stories were then featured in other publications and on TV, it was hardly surprising that much of the public believed the narrative. The tendency of mainstream media outlets to ignore or marginalize war critics amplified their pro-war bias.

As is so often the case with Trump’s arguments, his accusation that the press can cause wars is an exaggeration, but one that contains an important kernel of truth. Irresponsible media coverage has undoubtedly strengthened public sentiment for ill-advised wars in the past, and it could do so again in the future. The sometimes shrill hostility of the mainstream media towards Russia is pushing the United States toward an increasingly hardline policy that now borders on a second cold war. The original Cold War nearly escalated to a hot one on several occasions. The press needs to be doubly cautious about pushing policies that would send America down a similar perilous path. Trump is wrong to brand the press as an enemy of the people, but it is still a powerful institution that has not always used its great influence responsibly regarding matters of war and peace.

Ted Galen Carpenter, a senior fellow in defense and foreign policy studies at the Cato Institute, is the author of 10 books on international affairs, including The Captive Press: Foreign Policy Crises and the First Amendment.