What The Weekly Standard Has Wrought

There’s a sadness in the shuttering of any print publication, and The Weekly Standard is no exception. If its website is dismantled as the owners have suggested is likely, it will be a loss to the reading public and even to the world’s ability to understand itself. Any right-of-center reader would have found much to admire in the Standard, both in its early days and now. Christopher Caldwell, who has written for the magazine since its inception, has developed into America’s most important analyst of contemporary Europe. Andrew Ferguson always writes with wit and style. Several Heather Mac Donald essays have fiercely told the truth on the delicate subjects of race, policing, and political correctness on campus.

The term “bobo”—David Brooks’ coinage for the new sociological category of bourgeois bohemian—first surfaced in a Weekly Standard essay, and eventually became an American contribution to both the French language and the French description of their own society. The Standard’s polemics could be both civil and well-informed: one could read an attack of Pat Buchanan (when Buchanan’s presidential run was threatening the Republican establishment) and actually learn something about the lineage and successes of protectionist economics. There were occasional gems of the insider gossipy sort: who could resist the guilty pleasure of forwarding along Joseph Epstein’s recollection of meeting the 25-year-old Leon Wieseltier?

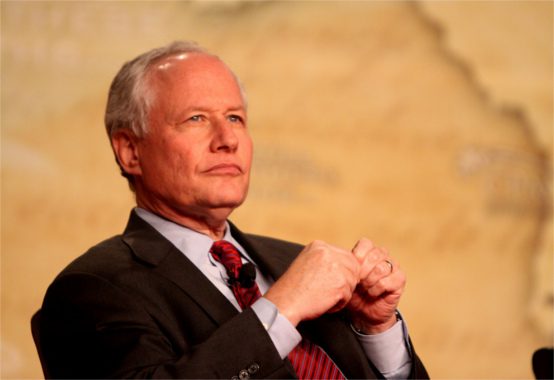

But all this, the work of gifted writers in high demand by many conservative outlets, is not the reason The Weekly Standard is an historically important publication. Nor is the fact that its most prominent figure, Bill Kristol, its founder, longtime editor, and, until it shut down, the editor at large, was an opponent of Donald Trump from the beginning. Nor that the magazine has maintained its Never Trump stance in the face of a more general GOP accommodation of the president. As the numerous television appearances by Kristol and other conservative opponents of Trump on liberal networks attest, Never Trumpism is not without its career enhancing benefits. In fact, the Standard’s opposition to Trump earned it a strange new respect among liberals. In a nearly hagiographic New York Times obituary, we are told the Standard was “a publication that was proudly heterodox from the start, eager to buck the prevailing values of conservative dogma and forge its own provocative point of view.”

Invariably left unsaid or minimized in such accounts (the Times devoted a full eight words to the subject) is the role the Standard played in fomenting the Iraq war, the sole policy question where the magazine’s role was unambiguous and decisive. Given the centrality of foreign policy to Kristol’s concerns, it is probably not too much to say that for the Standard, the main purpose of publishing the writers referenced above was to provide an attractive gift wrapping for neoconservative foreign policy advocacy.

It was far from obvious how the United States would respond after the terror attacks of 9/11. Pretty much everyone but pacifists agreed there would be a military campaign against the Taliban, which had provided a base for Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, and a campaign to destroy al-Qaeda, which had been conducting major terrorism operations in Africa and the Mideast. But Iraq was not on the radar for most. There were no serious connections between Saddam Hussein’s essentially secular dictatorship and a group bent on restoring a caliphate based on fundamentalist Islam. But Iraq had been on a neoconservative target list for years, with the neocons lamenting that George H.W. Bush had not pursued regime change and occupied Baghdad at the end of the first Gulf war. The United States had put in place heavy sanctions on Iraq, and there was a nominal congressional mandate for pursuing regime change by aiding dissident groups (the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998). But as neoconservatives themselves acknowledged in the 1990s, the idea of invading with American troops was a distant reach.

9/11 provided an opportunity to change that. As a glossy weekly publication, with hundreds of issues hand-delivered every week to important Beltway figures, the Standard occupied a critical node in Beltway opinion formation. Neoconservative think tank types could publish a piece there, and then go on Fox News (another Rupert Murdoch property) to reach non-magazine readers. And unlike most in the American government, Kristol knew exactly what he wanted America to do after 9/11: overthrow Saddam Hussein.

Since the mid-1990s, Kristol had been heading a small foreign policy think tank and lobbying group, the Project for the New American Century, dedicated to espousing a more hawkish foreign policy. Nine days after the attack, a PNAC letter laid out the new post-9/11 line. It conceded that the first priority was to dismantle the bin Laden network in Afghanistan (which would not require an invasion, it said) but overthrowing Saddam Hussein was the next priority. In a not-so-veiled warning to President George W. Bush, PNAC intoned, “Failure to undertake such an effort will constitute an early and decisive surrender in the war on terror.” The magazine’s first issue after 9/11 reaffirmed that line. The Standard’s war aims were laid out by two PNAC staffers, Gary Schmitt and Tom Donnelly, in a piece illustrated by a caricature not of Osama bin Laden but of Saddam Hussein. The approach they urged for the actual 9/11 hijackers was astonishingly mild: “While it is probably not necessary to go to war with Afghanistan, a broad approach will be required.” Taliban failure to help us root out bin Laden would be met with “aid to its Afghan opposition.” It would have been hard to find any member of Congress with a more dovish view.

Diverting the nation’s anger from bin Laden and towards Saddam Hussein was the priority. Wrote Schmitt and Donnelly, the “larger campaign must also go after Saddam Hussein. He might well be implicated in this weeks’s attacks or he might not. But…he is our enemy. Elimination of Saddam is the key to restoring our regional dominance.”

The magazine pounded this message relentlessly for months. Saddam was paired at the hip with Osama bin Laden in virtually every issue. “Who cares if Saddam Hussein was involved in the 9/11 attacks?” asked Max Boot. He, for one, did not, as he urged the American government to establish a regency on Baghdad to go with the one on Kabul. Reuel Mark Gerecht echoed PNAC, arguing that the war on terror would be a failure unless we removed Saddam. Stephen Hayes (later to become editor of the magazine) funneled intelligence scraps generated by a neoconservative nest in the Pentagon led by Douglas Feith to claim a relationship between Saddam and bin Laden that the CIA did not believe to be credible.

In a recent Twitter thread, Justin Logan linked to the some of the warmongering covers the Standard produced in the months after 9/11. They evoke the spirit of the publication, but can’t really do justice to the editors’ sheer skill at normalizing the idea that attacking a dictator with no connection to al-Qaeda was the only non-defeatist option. Seen in these terms, the Standard was a monumental success. It achieved its aims on a discrete policy issue more emphatically than any publication in living memory.

No less a student of the American political establishment than The New York Times’ Thomas Friedman speculated to a reporter from Haaretz that the Iraq war would not have happened without the machinations of two dozen people inside the Beltway:

It’s the war the neoconservatives marketed. They had an idea to sell when September 11 happened and they sold it. Oh boy, did they sell it. This is not the war the masses demanded. It is war of an elite. I could give you the names of 25 people, all of whom are at this moment within a five block radius of this office, who if you had exiled them to a desert island a year and a half ago, the Iraq war would not have happened.

Could this group have succeeded without Bill Kristol’s Weekly Standard serving as its public relations quarterback? Perhaps, but trying to imagine it led by the New York-based monthly Commentary or the American Enterprise Institute, without a glossy weekly and well-oiled entrée into Fox News studios, is difficult. As it was, the neoconservatives prevailed over the more cautious establishment figures within the administration like Colin Powell and Condi Rice and outside by George H.W. Bush veterans James Baker and Brent Scowcroft by a relatively narrow margin. War in Iraq was not inevitable; it was the culmination of concentrated political and ideological effort.

If the Iraq war was sold to the American establishment by a small elite, the price was borne by many. Estimates of the fiscal costs run from $1 trillion to as much as $3 trillion, (if you credit Nobel prize recipient Joseph Stiglitz’s calculations, which include the long-term care costs for American soldiers with lifelong and life shattering injuries). The human costs to the soldiers and their families was substantial. Throughout the Mideast, the number of people killed, wounded, or turned into refugees by the invasion was staggering. The American “regional dominance” touted by the Standard proved entirely fanciful.

Having more or less destroyed Iraq as a functioning country, the neoconservatives have now set their sights on Iran, their next candidate for regime change. In its final issue, the Standard touted the presidential ambitions of Nikki Haley. Few who follow politics are unaware that her preeminent qualification in the Standard‘s eyes is that she is a willing and attractive salesperson for hostility to Iran.

This essay began by acknowledging that something is lost when a sophisticated opinion voice falls silent. Yet the fact that those beating the drums for the next “regime change” war in the Mideast will have to do it without the glossy package of The Weekly Standard is not a bad thing.

Scott McConnell is a founding editor of The American Conservative and the author of Ex-Neocon: Dispatches From the Post-9/11 Ideological Wars.

Comments