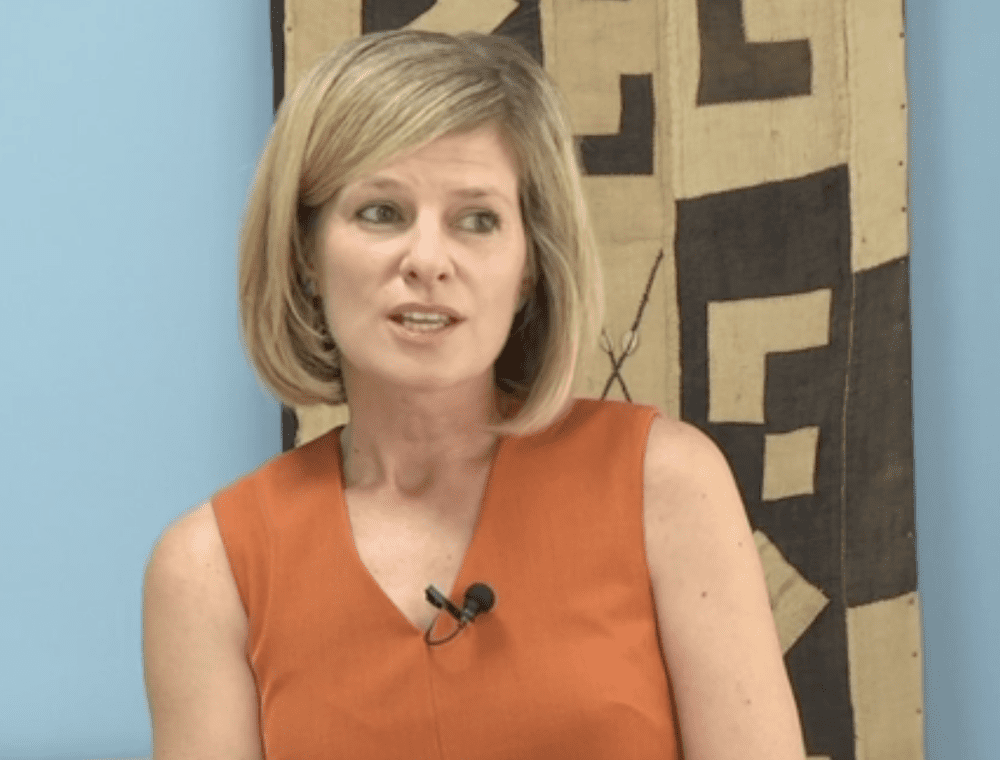

We Need More Government Dissidents Like Elizabeth Shackelford

U.S. foreign policy is marred by a lack of accountability. Not only is there no accountability in Washington for the failures of U.S. policies overseas, but the U.S. repeatedly errs in its dealings with client states by refusing to hold them accountable for their crimes and abuses.

Clients are permitted to act with impunity, and the U.S. never makes them answer for their outrages for fear of losing the leverage that it never uses. Instead of using the extraordinary influence that the U.S. has to rein in the abuses of its clients, our officials are more concerned with finding excuses for not wielding influence at all. The result is that the U.S. makes itself deeply complicit in the crimes of its clients at the same time that it renders itself impotent in advancing U.S. interests.

In her new book, The Dissent Channel: American Diplomacy in a Dishonest Age, Elizabeth Shackelford details how this persistent lack of accountability produced a perverse and dangerous policy of unconditional support for the South Sudanese government under President Salva Kiir. Despite horrific human rights abuses and ethnic cleansing committed by Kiir’s forces in the civil war, the Obama administration remained firmly supportive of South Sudan’s government. She describes the efforts that she and other Foreign Service Officers took to call attention to the failings of U.S. policy in the country, and she records how their warnings and recommendations were brushed aside and dismissed. Shackelford even resorted to using the State Department’s dissent channel to protest against Washington’s indulgence of Kiir, but to no avail. Her book is an important witness to the importance of capable diplomacy and the terrible cost that comes from failing to tell the truth about our own policies and the governments that we support.

Shackelford may be best known for her letter of resignation from the State Department during the brief Tillerson era, but the bulk of her story concerns South Sudan during Obama’s second term. She makes clear that the pathologies of U.S. foreign policy that she criticizes are not a recent development. She is unsparing in her fair criticism of the mistakes of senior Obama administration officials, especially Susan Rice in her capacity as National Security Advisor. Shackelford identifies Rice as one of the main people responsible for setting what she regards as a horribly misguided policy in South Sudan, and she puts it in the context of Rice’s habit of backing abusive and authoritarian governments elsewhere in Africa. According to Shackelford, “Once she had chosen someone to support, her loyalty became unshakable.” That might be an admirable trait in a friend or a political ally, but in a top U.S. official responsible for foreign policy and national security it is a disaster in the making.

Shackelford does a superb job in recounting her years serving at the U.S. Embassy in Juba, and she has told an unflinchingly honest story about the disconnect between official U.S. policy and the reality of what was happening in South Sudan. It is also a tribute to the diligent people who serve their country in the Foreign Service under difficult and dangerous conditions all around the world. The most important thing that the book does is to show how the desire to support the fledgling democracy in South Sudan was exploited to ignore and whitewash atrocities committed by that government. Maintaining the relationship and propping up a particular leader became ends in themselves and everything else was subordinated to them.

One example of how this worked in practice was the resistance to cutting off military aid in response the government’s recruitment of child soldiers. Shackelford remarks that refusing to give military aid to a government that uses child soldiers “seemed like a simple thing we could all agree on, but in South Sudan, we seemed capable of justifying any accommodation.” Much like later rationalizations of military support for Saudi Arabia, the argument offered up was that the U.S. could only improve things by continuing to provide aid. Even though the U.S. would have been perfectly justified in withholding aid over this issue, it refused to use the leverage it had, and of course there was still no improvement.

As Shackelford says, “Dissents don’t typically identify problems no one saw coming. They usually identify problems we willfully chose to ignore.” That is unfortunately the story of many U.S.-client relationships over the decades, and in the case of South Sudan the desire to ignore reality was particularly strong because of the U.S. role in helping to bring the country into existence. Because the U.S. invested so much in securing South Sudan’s independence, there was an even greater reluctance to criticize its leadership. She notes that “no one seemed willing to muddy the narrative that had led to an independent South Sudan…For years, South Sudan’s many Western friends refused to admit a more complicated story line. We conveniently glossed over the pieces that didn’t fit.” That encouraged Kiir and his allies to assume that they could get away with just about anything without jeopardizing Washington’s support.

The circular reasoning of the enablers is always the same: using leverage with another government means losing influence, and that is why the U.S. must never use leverage so that it can retain influence that it will never wield. Shackelford recounts her baffling conversation with Donald Booth, the U.S. special envoy:

As though it was the most logical argument imaginable, Booth explained to me that we couldn’t follow through on the threats because they were our only leverage, and once we followed through with the threatened actions, we wouldn’t have them to threaten anymore.

“Then what’s the point of the threats if we aren’t willing to follow through, and they know that?” I asked honestly. His reply was circular: that we needed to keep the leverage of making the threat but couldn’t use it or we would lose the option. (p. 252)

U.S. officials have employed this argument countless times to explain why the U.S. can’t stop supporting the Saudi coalition war on Yemen, why it can’t cut off military assistance to the Egyptian dictatorship, and why it can’t suspend aid to Israel over its illegal occupation and annexation. The most powerful government in the world preemptively ties its own hands to give itself cover to continue supporting the abusive governments that it wants to keep supporting. Client relationships are supposed to be useful to the U.S. in advancing our interests, but in practice the U.S. spends most of its time and energy catering to the preferences of its clients while compromising on our respect for international law and human rights.

One of the many problems with ignoring the abuses of clients and providing diplomatic cover for the abusers is that it encourages U.S. officials to lie to themselves and to the public about these governments and the role that the U.S. has in enabling them. In order to deflect attention from U.S. complicity in atrocities, they will tell a story about how the U.S. needs to continue its assistance and support in order to improve the situation. That conveniently ignores that U.S. assistance and support have helped to create the conditions for the abuses in question. This is how an argument for impunity gets dressed up as concern for stopping abuses. It is how aiding and abetting crimes become “engagement.” This keeps the U.S. committed to bankrupt policies that only encourage more destructive behavior from clients on the basis of a lie. Shackelford comments on this recurring problem in U.S. foreign policy:

As it turns out, lying to yourself leaves you ill-prepared to effectively address foreign policy challenges. This is the cost of closing your eyes and systematically suppressing dissenting views. (p. 242)

It is not surprising that the U.S. keeps driving itself and other countries into the ditch because it prefers to keep its eyes closed to inconvenient truths about the governments that it chooses to support. An honest reckoning of the costs and benefits of these relationships would force the U.S. to acknowledge that it doesn’t need to carry water for any of these governments. The U.S. can still have constructive and cooperative relations with many of these states without brushing evidence of their most sordid behavior under the rug.

“Washington chose not to learn what we didn’t want to know,” Shackelford writes of the failure to hold South Sudan’s government accountable. That described U.S. mistakes in the years leading up to the start of the civil war in 2013, but it could easily describe many other foreign policy errors that the U.S. has made. Facing and speaking the truth about U.S. clients might be politically difficult on occasion, but it will make for much better-informed and responsible policies than blindly lurching from one crisis to the next. U.S. officials owe it to the American public and to the people in these other countries to be honest in their assessments and to call out unacceptable behavior when they see it. Above all, we need to start listening to the dissenters before it is too late.

Comments