They Got Saudi Arabia Wrong Too

Mohammed bin Salman cuts a dashing figure. Here’s a Saudi royal, in his early 30s, who speaks about ushering in an unprecedented transformation of the Kingdom’s fossilized society. His elevation to crown prince in 2017 was interpreted by much of the West as a godsend to modernity, free markets, and 21st-century thinking. American foreign policy elites ate up MbS’s sales pitch like a New Yorker eats pepperoni pizza: with delight in their eyes and joy in their hearts. Finally, a prince from a younger generation was working to bring Saudi Arabia—the land of oil, sword dancing, and Islam’s two holiest cities—towards a brighter future. Women would be driving soon; Western businesses would be investing in something other than the energy sector.

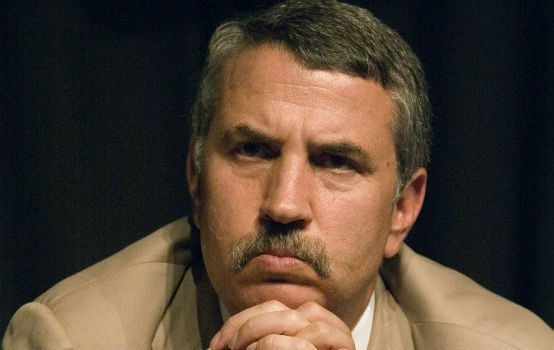

Thomas Friedman, the bestselling author and long-time New York Times columnist, bought MbS’s story hook, line, and sinker. After jetting to Riyadh for an exclusive interview with the crown prince last November, Friedman wrote about bin Salman as if he was the very best Saudi Arabia had to offer. In one of his more naive dispatches, Friedman described Saudi Arabia as being on the cusp of its own Arab Spring. The rich and entitled royals were finally getting punished for stealing from the state’s coffers. “Not a single Saudi I spoke to here over three days expressed anything other than effusive support for this anticorruption drive,” Friedman observed in his column. Of course, given that the Kingdom is an absolute monarchy and MbS has a reputation as a petulant child, why Friedman expected anything other than glowing assessments from Saudis is puzzling.

In the last two weeks, by virtue of his actions, the crown prince has demonstrated to the entire world his true character: as intolerant of dissent and as obsessed with blind loyalty as every other autocrat in the Arab world. He is a reckless and bumbling amateur who plunged his country into a self-defeating cycle of mistakes, quagmires, and diplomatic imbroglios; an insulated princeling more in line with a mob boss than the squeaky clean anti-corruption crusader he is trying to sell himself as. Tom Friedman and members of the Trump administration may have largely accepted his narrative, but for the rest of us who have watched the total decimation of neighboring Yemen and the near-starvation of 13 million Yemenis, no public relations firm in the world can polish the giant turd the crown prince has laid at his own Kingdom’s doorstep.

Since the disappearance and murder of Jamal Khashoggi at the likely hands of a Saudi hit squad, Friedman has issued a mild mea culpa of sorts. Days after the Khashoggi story broke, he reminded readers that while he was excited about MbS’s potential as an economic and social reformer, it wasn’t like he was starry-eyed about him. And as with the rest of the foreign policy establishment in the Beltway, Friedman’s non-apology will be enough. He will continue to be invited to conferences the world over, continue writing columns for America’s paper of record, and continue selling books at a record clip. The media will continue to book him as a renowned foreign policy expert, despite his dubious track record in offering advice.

To be fair to Tom Friedman, everybody is entitled to make mistakes. I, too, have made a few in my life; no one is perfect after all. The big difference, however, is that poor judgment in foreign policy can get a lot of people killed, drawing countries into strategically foolish wars that upend regional stability and push national debt into the stratosphere. If the foreign policy community policed itself a little better and abandoned its systemic unaccountability—unaccountability that allows the cheerleaders of some of our nation’s worst foreign policy disasters to remain on our television screens and in our newspapers (Bill Kristol, Stephen Hayes, Bret Stephens, and Marc Thiessen, to name just a few)—perhaps we would all be better off.

Jamal Khashoggi’s state-sanctioned murder is a despicable act of depravity. But there is a lesson to be learned that is bigger than Khashoggi, Mohammed bin Salman, and even the U.S.-Saudi relationship: the elites who have been influencing public opinion for decades should no longer get a pass. They need to be called out and made to answer.

Daniel R. DePetris is a foreign policy analyst, a columnist at Reuters, and a frequent contributor to The American Conservative.

Comments