The Decline and Fall of New York Democracy

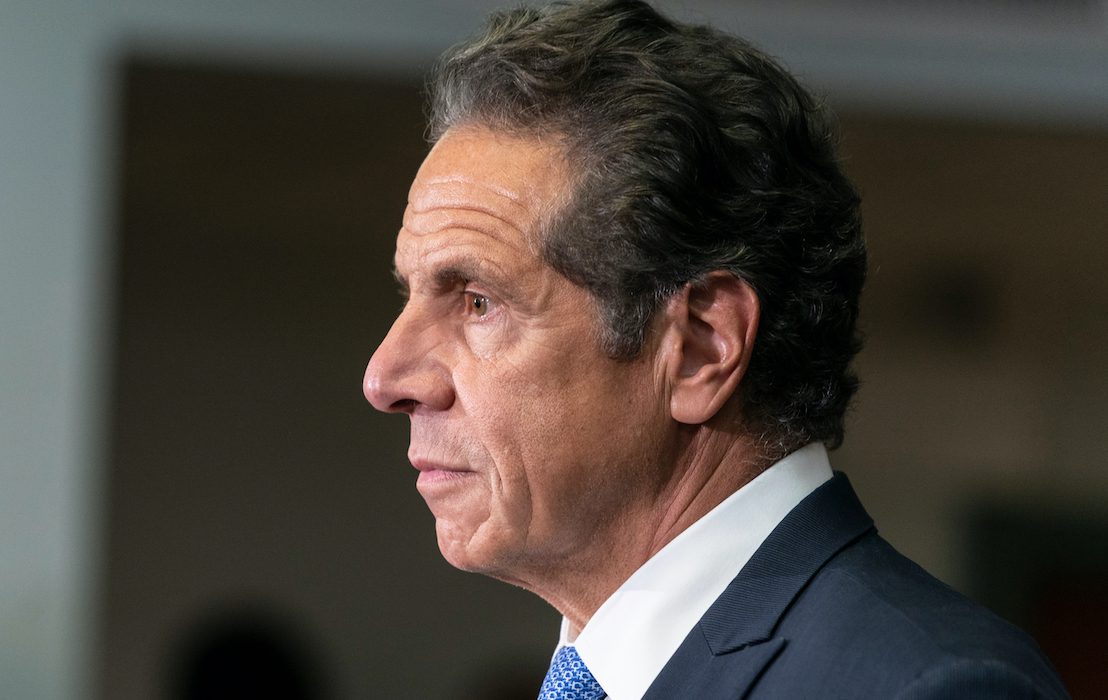

The recent ignominious departure from office of Andrew Cuomo is the latest act in New York’s sad saga of political decline. Cuomo fell because of his private life, such as it was; the right thing for the wrong reason.

The standards applied to him would have victimized, among others, the state’s 49th governor, Nelson Rockefeller. Cuomo’s manipulation of nursing home statistics would have been an appropriate ground for forcing his departure; groping was not, unless we are to make of sexual harassment law a blackmailer’s charter. The facts of these matters cannot be accurately determined, especially when time has passed, and in any event they are largely irrelevant to performance in public office, though the greatest leaders, e.g. Winston Churchill and Charles De Gaulle, avoid such hazards.

Cuomo liked to throw his weight around, never more so than in his Covid-19 mandates addressed to the New York restaurant industry. One must hope that he has developed a fondness for home cooking. Why he became governor is something of a mystery; at HUD he bore more than a little responsibility for the Community Investment Act and consequent “toxic waste” recession. Like his father, he was almost purely a rhetorical politician; Mario Cuomo’s greatest service to the nation in his 12 years in Albany was in twice declining a Supreme Court nomination.

The other post-World War II New York Democratic governors have likewise, with the exception of the under-appreciated Hugh Carey, been disappointing. Carey, unlike the senior Cuomo, bravely faced up to New York City’s fiscal problems. For Averell Harriman, a one-term New York governorship was but a spring-board; acting Governors Poletti and Patterson were not in office long enough to make an impression. The state’s post-war Democratic senators, with the magnificent exception of Daniel Patrick Moynihan, have also been a dismal lot, never more so than at present. For the divisive celebrities Robert Kennedy and Hillary Rodham Clinton, the New York Senate seat was always just a launching pad for higher ambitions.

It is therefore appropriate to remember and reflect on the glory days of the New York Democratic party, from 1920 to 1946, when the party produced three outstanding governors: Alfred E. Smith, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Herbert H. Lehman.

Smith was an original; notwithstanding his Tammany Hall background, his administration—with its old age pension, safety, and unemployment and disability insurance laws—laid the foundation of the American welfare state, such as it is, and along with Maryland’s Albert Ritchie he provided the political foundation for the repeal of alcohol prohibition. He was also a self-taught champion of civil liberties, in his opposition to the Lusk laws and the expulsion of socialists from the New York legislature. His liberalism was of the so-far-and-no-further variety; he endorsed Willkie in 1940. His two most notable aides are also undeservedly forgotten. Belle Moskowitz, the “mother” of the welfare state, was the subject of the largest public funeral in the history of New York at the time of her death; and Judge Joseph Proskauer, a leading trial lawyer and Jewish anti-Zionist who helped prompt President Eisenhower’s “don’t join the book-burners” speech before his death in the 1950s.

Although Judge Learned Hand, among others, doubted Franklin D. Roosevelt’s essential benevolence and regarded him as a gifted manipulator, Roosevelt’s commitment to conservation and to youth employment was not in doubt, as governor and as president. When the director of his Civilian Conservation Corps lay dying in a Washington hospital in the 1930s, Roosevelt spent more than the usual amount of time with him. His accomplishments, controversial among conservatives, are nevertheless beyond dispute.

Herbert Lehman, Roosevelt’s designated successor, was not a brilliant man, but was an exceptionally honest one. During one of his campaigns for governor against the vituperative Robert Moses, Lehman was criticized for being a director of a large workingmen’s bank that failed during the Depression, and in whose demise Governor Roosevelt was not blameless. It was not until the campaign was over that it was disclosed that Lehman had dedicated a large part of his personal fortune to a vain effort to prop up the bank. It was Lehman also who, in an exhibition of non-partisanship inconceivable in our time, delivered the coup de grâce to President Roosevelt’s plan to pack the Supreme Court. In his later years, Lehman became a U.S. Senator, best remembered for his denunciations of McCarthyism. These made him for a time a pariah in the Senate, but they were not unpopular in New York. I remember being moved by one of them as a teenager: “They use and abuse the constitutional safeguards for the free exchange of ideas, while cynically seeking to destroy the soul and spirit of the nation whose name they invoke.”

My father spent his later years as curator of the Lehman archive at Columbia University, for which he also acquired the archive of Lehman’s lieutenant governor and successor, Charles Poletti. The archive, however, was accompanied by a large and florid bust of Poletti, executed in the Hollywood manner. In his effort to dispose of the bust, my father, who had acquired the Italian language in his youthful travels, invited the director of Columbia’s Casa Italiana to lunch. After a pleasant conversation in Italian, the two began walking back to the Casa Italiana, at which time the matter of the bust was delicately broached.

The temperature dropped about 20 degrees, the language of conversation abruptly shifted from Italian to English, and the director declared: “Mr. Liebmann: There are only two busts in the Casa Italiana. One is of Michelangelo and the other is of Dante, and we are not about to add Charlie Poletti to our collection!” Poletti was a worthy enough person, and after the remainder of Lehman’s term expired was made American military governor of Italy. He favored a prolonged military occupation on the German model, but lost out to his British counterpart, Harold Macmillan, who favored a swift return of government to the Italians, while conceding that “self-government is not necessarily good government.”

These governors were all a far cry from the Cuomos. The decline in New York’s Senate delegation on the Democratic side is equally discouraging. The New York Democrats once contributed Robert Wagner Sr., Lehman, and Moynihan. We now have Kirsten Gillibrand, a noted enemy of the right of cross-examination for accused college students, who opposed confirmation of virtually all Trump appointees, including the worthiest of them. Charles Schumer’s threats to and demonstrations at the Supreme Court must have caused Herbert Lehman to turn in his grave.

New York has a worthy tradition of moderate Republicanism, on the other hand. Its Republican governors include Theodore Roosevelt, Charles Evans Hughes, Thomas E. Dewey, chiefly remembered for the New York throughway; Nelson Rockefeller, whose principal achievement was the enlargement of the state university system to include four major research universities at Binghamton, Buffalo, Albany, and Stony Brook; and the frugal manager George Pataki. The recent Republican Senators likewise have been an above-average lot, including Irving Ives, Jacob Javits, Kenneth Keating, James Buckley, and “Mr. Pothole,” Alphonse D’Amato. The Republicans also supported the inimitable Congressman and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, whose Norris-La Guardia Act brought an end to clashes between labor unions and the U.S. Army, fostering national unity in the run-up to World War II.

One reflecting on the downfall of the New York Democracy must call to mind the words of the railroad president Charles Francis Adams in his “Chapters of Erie,” quoting the third act of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, on the decline of the New York judiciary from Chancellor Kent to the satraps of the Tweed Ring: ”Could you on this fair mountain leave to feed. And batten on this moor?”

George Liebmann is president of the Library Company of the Baltimore Bar and the author of numerous works on law and history, most recently America’s Political Inventors (Bloomsbury) and Vox Clamantis In Deserto: An Iconoclast Looks At Four Failed Administrations (Amazon).

Comments