Taking Off the ‘What Would William F. Buckley Do?’ Wristband

I landed my first job in journalism when I was 20 years old. It was my second year as an undergraduate at the University of Sydney. I’d written an article for Quadrant about the unceremonious and unconscionable firing of my friend, mentor, and thesis supervisor Barry Spurr. (Incidentally, I learned from a recent Prufrock newsletter that Barry has been appointed Quadrant’s new literary editor.)

About a week after the article was published, the editor asked me to stop by Quadrant’s offices and offered me a job. He was taking a leave of absence and was on the lookout for an ambitious young wordslinger to help the new guy find his bearings.

As it happens, the new guy was John O’Sullivan, who succeeded William F. Buckley at National Review in 1988. He’s the finest writer and editor I’ve ever met, and as kind and cultured a man as ever lived. I could write a long essay lavishing praise on him, and I will someday.

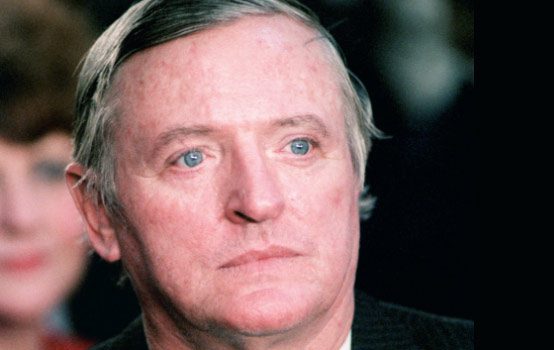

John was also (to my mind) a kind of second-class relic. I’d been a devotee of WFB since middle school, and this new career in journalism gave me reason to indulge my obsession during business hours. Imagine my thrill when, at an after-work drinkie-do, John said I reminded him of a young Bill Buckley. Maybe it was the fourth gimlet doing its work on my tired brain, but I had to choke back tears.

Of course, I’m not the first young hacksickle to worship at the altar of WFB, and I won’t be the last—not while The Bulwark (The Fireship?) is still churning out copy, at least. Over at that last, best hope for the Conservative Movement™, Zachary Shapiro brings the Cult of Buckley to heights that the 20-year-old me would have found immediately convincing. “WWBBD: What Would Bill Buckley Do?” Shapiro asks, coining a phrase that was no doubt on many wristbands at this year’s CPAC.

Shapiro sketches a blueprint for anyone thinking about running against Trump in the GOP primary, which is based on Buckley’s abortive 1965 run for mayor of New York. It’s a good strategy, if only because it requires the challenger to acknowledge from the outset that he doesn’t have a snowball’s chance of unseating the incumbent.

In fact, a young Michael Warren Davis would have admired Shapiro all the more for preserving the whiff of martyrdom that hung around the conservatism of the 1960s. I longed for the excitement and vitality of an embattled intellectual vanguard. It was like being Guevarista, except one got to go home at night to warm brandy and Grecian slippers.

Alas, my Buckleyism has dwindled in the years since I left Australia. In fact, I’ve spent much of that time trying to understand why I worshipped him in the first place.

♦♦♦

After all, even his most devoted followers must admit that Buckley was a middling journalist. Most probably can’t recall a single article he wrote, let alone name their favorite. His lack of original thinking was buoyed by his infamously florid prose, which, like Coca-Cola, has no nutritional value and needs to be consumed along with great helpings of heartier, blander fare.

Rather like Charles Krauthammer, his best work had nothing to do with current affairs. Krauthammer’s great muse was chess; Buckley’s was peanut butter. My fiancée and I remember very distinctly the conversation we had about Buckley’s odes to peanut butter on our first date. They’re exquisite.

For that matter, his column on smoking—one of his last published pieces, which ran three months before his death from complications of the same—is the manliest treatment of that exquisite vice (one that I also struggle with) ever set to paper.

So, too, his television show Firing Line. There he was, with his Brooks Brothers shirts (another shared vice) and trans-Atlantic accent (ditto), his flickering eyes and prehensile scalp. He’d spend an hour poking himself in the face with the butt end of a pencil, making windy, intelligent-sounding noises at famous people.

This was the beginning of the “gladiatorial” genre of current affairs television: popular and strong personalities engaged in gory combat that, at the end of the day, doesn’t really aspire to change hearts and minds. Bill O’Reilly and Tucker Carlson are his true heirs in this respect.

It’s all a great deal of fun, but WFB’s own performances weren’t especially edifying. He was soundly thumped by Noam Chomsky on the Vietnam war, for instance. Again, he’s at his best on basically unserious topics, such as: “To what extent, precisely, is a well-adjusted American able to humor a Hare Krishna?”

Of course, had he chosen just one field, Buckley could have truly excelled. He might have been an excellent feature writer or a superb talk show host, if he’d only put his heart into it. Instead, Buckley is remembered as a political operative. And though he never led the GOP, he did run its politburo for some three decades. In that capacity, he’s remembered as the “father of American conservatism”—or, at any rate, its midwife.

♦♦♦

We all know the story: WFB herded traditionalists, libertarians, nationalists, agrarians, Catholics, and an Austrian royalist under the masthead of his magazine, which he gave the inspired name of National Review. Frank Meyer fused them together in a new ideology, which was given the inspired name of fusionism. Buckley didn’t found the Conservative Movement™, but he owned the trademark.

Originally, National Review’s contributors were united only by their opposition to communism, progressivism, and everything to the left of William F. Buckley. Which is all fine. Then in the 1960s, the John Birch Society accused President Dwight D. Eisenhower of being a communist himself. Buckley declared the Birchers anathema, and National Review was now united by its opposition to everyone on WFB’s right as well.

That’s all fine, too, as far as I’m concerned. Buckley proved himself a capable gatekeeper for respectable right-of-center opinion. But then he bungled the infamous neoconservative-paleoconservative split of the late 1980s and early 1990s, siding with the come-lately neos against his longtime paleo allies.

Take, as a case study, the 1986 feud between Midge Decter and the late Joe Sobran. From their private correspondences, it’s clear Buckley doesn’t believe Decter. He can’t agree that Sobran’s weariness towards Israel is, in fact, a thinly veiled animus towards the Jewish people. Nevertheless, he obeys Decter and asks his protégé to step down as senior editor.

Sobran was evidently of the opinion that, if a man is going to be treated like a mad dog, he may as well act like one. Not only did he resign as editor, he disowned National Review altogether. And things got incrementally worse from there. The slow unraveling of this brilliant man has done much to justify Buckley’s disgraceful treatment of his old friend—and the excommunication of paleocons from the Conservative Movement™ more generally—ex post facto.

Buckley was ill at ease with his new bunkmates, however. In 2004, he said that neocons “simply overrate the reach of US power and influence.” In 2005, he called regime change and wars of democracy “terribly arduous.” Yet he refused to put himself at odds with the new Republican establishment.

And so, while the magazine remained entangled with its neoconservative allies, he rallied behind the last remaining member of the original National Review coalition: the libertarians. Hence, he declared National Review’s support for recreational narcotics in 1996—almost two decades before The New York Times. This remains one of the magazine’s great boasts; it also, perhaps, marks the exact moment when the Conservative Movement™ threw in the towel on social issues.

♦♦♦

When Buckley died in 2008 (requiescat in pace), American conservatism bore virtually no resemblance to its old 1955 self. Some change is good, but often the pendulum swings entirely to the opposite extreme. A magazine that once declared that “the South must prevail” against desegregation now calls for states to “mothball” statues of Confederate war heroes.

Other changes were, perhaps, less than desirable from the get-go. This High Tory could do without the increasing defeatism on social issues and the pivot towards radical free-market economics. I prefer diplomacy to war; even more than diplomacy. I prefer keeping my nose out of other countries’ business. And I don’t appreciate being called “unpatriotic” for doing so.

I liked the National Review of Russell Kirk, who recalled how his father “looked back to the old rural tranquility of brick farmhouses and horses and apple orchards and maple groves from which he was swept away by the tide of industrialism.” What arrives in my mailbox now is the National Review of Kevin Williamson, who says of “the white American underclass”: “Economically, they are negative assets. Morally, they are indefensible.”

What remains in the Conservative Movement™ of the old Buckley, before he made it big and lost his way? Nothing, alas, but the excommunications. National Review famously tried Sobraning then-candidate Trump in 2016. Trump responded by saying Buckley would be “ashamed” of National Review’s editors, which I don’t think is true, though maybe he ought to have been.

One wonders if Trump, like Sobran, was “radicalized” by the heavy-handedness of the National Review-led conservative elite. Regardless, it showed that Movement and Populist conservatives are both eager to claim Buckley’s mantle and will brook no rival pretenders. Pope, meet Anti-Pope.

No offense to WFB, but I think I’ll find a different role model—one who’s a little more consistent. What would Edmund Burke do?

Michael Warren Davis is associate editor of the Catholic Herald. Find him at michaelwarrendavis.com.

Comments