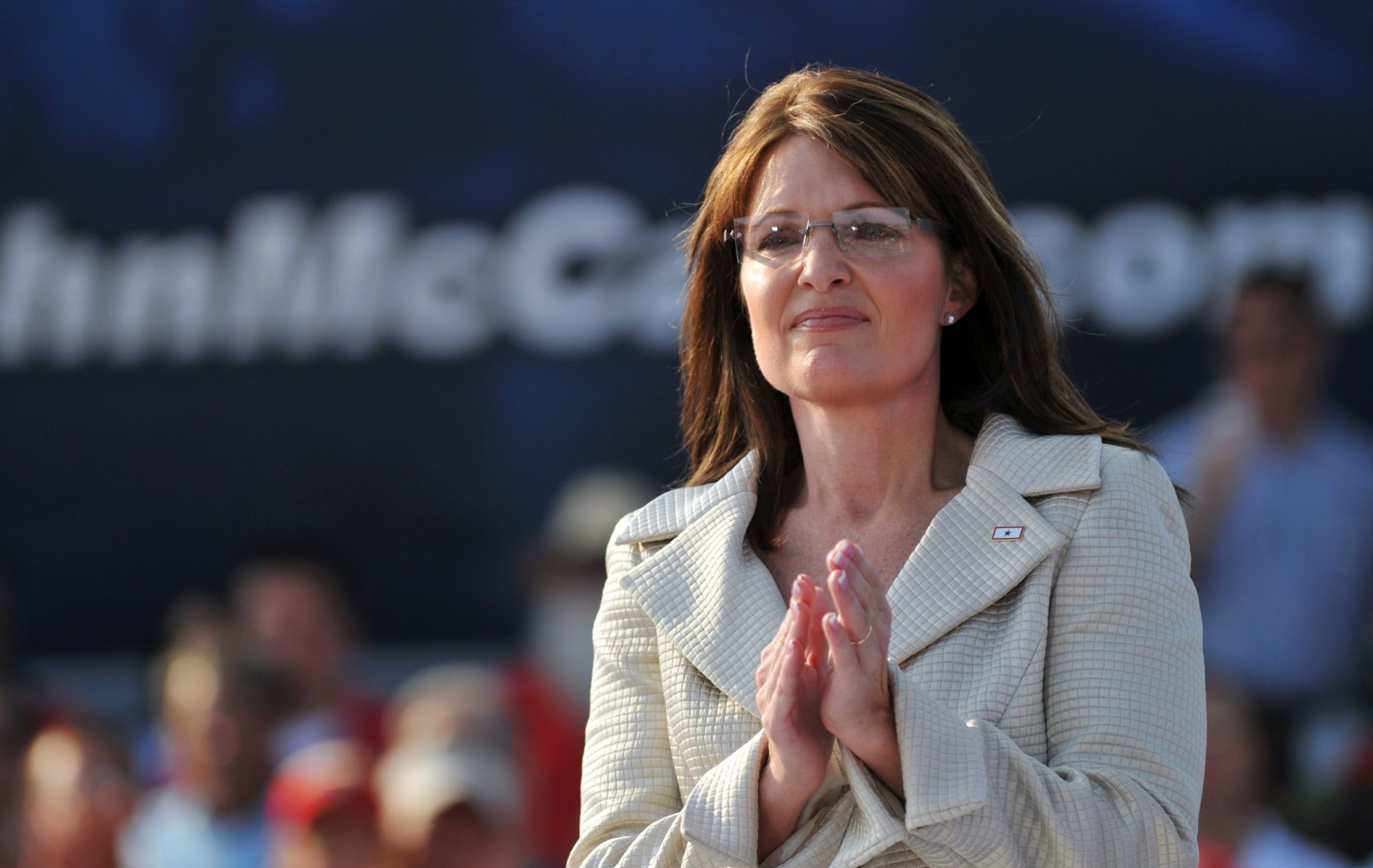

Sarah Palin Takes on the New York Times

What is Sarah Palin up to, suing the New York Times for libel? Is she really trying to change the First Amendment? Does she know what she is doing?

Palin v. The New York Times Company is now before a district court in New York, and, regardless of the outcome, is almost certainly headed for the Supreme Court. The plaintiff seeks to overturn precedent that gave America some of the world’s strictest libel laws. If other media you consume is still treating this all as just another kooky Nailin’ Palin story, you’re looking at the wrong sources.

The story begins on June 14, 2017, when a left-wing nut-job shot at Republican politicians playing baseball in Virginia (wounding, among others, Louisiana’s Steve Scalise). The New York Times wrote at the time:

Was this attack evidence of how vicious American politics has become? Probably. In 2011, when Jared Lee Loughner opened fire in a supermarket parking lot, grievously wounding Representative Gabby Giffords and killing six people, including a 9-year-old-girl, the link to political incitement was clear. Before the shooting, Sarah Palin’s political action committee circulated a map of targeted Democrats that put Ms. Giffords and 19 other Democrats under stylized cross hairs.

The Times quickly issued multiple corrections, pointing out it had,

incorrectly stated that a link existed between political rhetoric and the 2011 shooting of Representative Gabby Giffords. In fact, no such link was established. The editorial also incorrectly described a map distributed by [Palin’s] political action committee before that shooting. It depicted electoral districts, not individual Democratic lawmakers, beneath stylized cross hairs.

Palin filed a libel suit stating the Times defamed her by claiming her PAC’s advertising incited people to violence, which the Times knew was not true. The suit was initially dismissed, but after five years of wrangling, Palin got the case reinstated.

Under current law, three criteria have to be met to prove a charge of libel. Palin first has to show what the Times wrote was false; this is not in contention, as the Times issued a correction. Second, she has to show that what the Times wrote was defamatory, meaning it harmed her reputation. Third, she has to show “actual malice”—that is, the Times knew what it published was false or showed reckless disregard for the truth.

The rules for libel cases between the media and public figures goes back to 1964’s Sullivan v. The New York Times Company, when the Supreme Court held the First Amendment protects the media even when they publish false statements, as long as they did not act with “actual malice.”

In Sullivan, the dispute arose after civil-rights leaders ran a full-page fundraising ad in the Times describing “an unprecedented wave of terror” wrought by police against peaceful demonstrators in Montgomery, Alabama. Their specific allegations were not all true, and the advertisement made the police look worse than they were. So L.B. Sullivan, in charge of the police response in Montgomery, sued the New York Times for libel, claiming they printed something they knew was false and damaged his reputation. An Alabama court agreed and the New York Times was ordered to pay $500,000 in damages.

The Times appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that if a newspaper were required to check the accuracy of every criticism of a public official, freedom of the press would be severely limited. The First Amendment, they argued, required the Court to give the benefit of the doubt to the media in cases involving public officials. The Court sided with the Times, and created a new standard for libel of a public figure, “actual malice,” defined as knowing a statement was false but publishing it anyway, or publishing a claim with “reckless disregard” for truth. The Court’s Sullivan framework is why the New York Times has not lost a libel case in America ever since.

As part of the decision, Justice William Brennan asserted America’s “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” Free and open debate about the conduct of public officials, the Court reasoned, was more important than occasional factual errors that might damage officials’ reputations.

In context, Sullivan freed Northern journalists to aggressively cover racial issues in the South, shielded from libel suits. It represented a significant broadening of the First Amendment.

In Palin’s case, to stay within the framework of the Sullivan precedent, the Times is arguing their article did no harm to Sarah Palin. She continues to bop around the national political arena doing whatever it is she does. Palin’s side is arguing the Times had no evidence her PAC incited anyone in the instant shooting case, and that the Times employee who wrote the original article thus exhibited “reckless disregard” for the truth. The case is in early days, but everyone already can map out the forthcoming arguments based on the criteria in Sullivan.

A lot of journalistic slush has flowed downhill since Sullivan in 1964, and attitudes toward the media have changed. The media of 1964 wanted to be objective, or at least give the appearance of being objective. In 2022 places like the Times wear their partisanship as a badge of honor and mock people like Sarah “Caribou Barbie” Palin. They spend years covering stories with reckless disregard for the truth, whether it be fake WMDs in Iraq or “Russiagate.” The glory days of NYT’s reporting on the Pentagon Papers or Watergate are long gone.

The Supreme Court justices who wrote the Sullivan decision are also long gone. Completely separate from Palin’s lawsuit, last year Justice Neil Gorsuch added his voice to an earlier statement by Justice Clarence Thomas questioning Sullivan.

Thomas, in a libel-case dissent, scolded the media over its publication of conspiracy theories and disinformation. He cited news reports on “the shooting at a pizza shop rumored to be the home of a Satanic child sex abuse ring involving Hillary Clinton” and a NYT article involving “online posts falsely labeling someone a thief, a fraudster and a pedophile.” Thomas wrote that “instead of continuing to insulate those who perpetrate lies from traditional remedies like libel suits, we should give them only the protection the First Amendment requires.”

Siding with Thomas, Justice Gorsuch wrote that the media in 1964 was dominated by a handful of large operations that routinely “employed legions of investigative reporters, editors, and fact checkers… Network news has since lost most of its viewers. With their fall has come the rise of 24-hour cable news and online media platforms that monetize anything that garners clicks.”

Gorsuch is clear: The changing media landscape requires the Court reassess Sullivan. Now, the Court has a conservative majority that might be ready to do so. In the background is Donald Trump, whose criticism of existing libel laws, focused on Bob Woodward’s books about his presidency, is well known.

This is the immediate context of Sarah Palin’s case against the New York Times. It is a difficult case, particularly for those who support broader First Amendment rights. A ruling that weakens or nullifies Sullivan and declares Palin the winner would have an inevitable chilling effect on the media. Maybe not super-media like the Times, which has money for lawyers and always relishes a good First Amendment fight, but smaller outlets who cannot afford to defend themselves. Everyone remembers the demise of Gawker.

If the Court rules against the Times, the media will have only themselves to blame. Given that Sullivan ensures close calls always fall their way, too many in the corporate media purposefully exploited that gift, using the First Amendment as a dummy front to pass off untrue garbage and shameful partisan propaganda as fact.

In a post-Sullivan world, it is unlikely that Russiagate would have been a three-year media event. Libel suits would have stopped the whole thing cold. As Justice Gorsuch wrote, the Sullivan standard Palin is contesting has offered an “ironclad subsidy for the publication of falsehoods” for the media to disseminate sensational information with little regard for the truth. Maybe it is time to change that.

Peter Van Buren is the author of We Meant Well: How I Helped Lose the Battle for the Hearts and Minds of the Iraqi People, Hooper’s War: A Novel of WWII Japan, and Ghosts of Tom Joad: A Story of the 99 Percent.