Safety Third: Covid-19 and the American Character

In the summer of 2021, I spent a week in northwest Montana. It was easy to forget there was a pandemic going on. People were zip-lining, hiking, whitewater rafting. The family who lived next to the house that we rented invited us—total strangers—into their home for drinks (sans masks), and all of our children played together a bit each day. At the end of our trip, we saw a beat-up truck with a wonderful bumper sticker: “Safety Third.” We laughed at what seemed to be a perfect summation of the carefree attitude that allowed the rugged sort of liberty we had seen in Montana.

Seven months later, much of the nation remains in the grips of authoritarian overreach. The draconian policies that have been implemented to “shut down the virus” have failed. In fact, it has been obvious for the better part of a year that the virus can’t be “shut down.” By now, it should be clear to everyone that the pandemic is being leveraged by the media, corporate entities, government, and the medical establishment to justify more regulatory insanity, imposing control over the minutiae of daily life.

So far, this power grab has gone largely uncontested. In less-densely populated states like Montana, citizens retain a good deal of individual liberty, and large states like Texas and Florida have protected personal freedom. But most of this is thanks to the election of conservative-minded officials, rather than any organized popular resistance. Indeed, the public demonstrations against Covid tyranny in Europe and Canada have dwarfed any American opposition in terms of size and frequency. This should be a source of embarrassment for a nation with such a rich history of liberty and civic engagement.

Why, then, have Americans been reluctant to push back against the abuses of power that have unfolded since the onset of the pandemic? Sadly, the answer seems to be not so much “fear” as safety. An obsessive concern for safety is a particular kind of fear: It is a generalized apprehension of the world and the different ways it threatens our comfort and well-being. That so many Americans are so worried about their own safety and that of others—due to an illness that over 99 percent of people will survive and fully recover from—speaks poorly of any free nation. But it is especially unbecoming for Americans, because we have never been a “safe” people.

“But who are ‘we’?” I can hear the leftist scolds singing in my imagination. “That’s not who we are!” was a favorite phrase of Barack Obama, albeit one that was always deployed cynically. For him, “we” betrayed our identity when (and only when) the public expressed distaste for the policy whims of the progressive left. But since those halcyon days of Obama ended, it has become fashionable to pretend that the American polity is so diverse that it’s impossible to make any generalizations about our collective identity. Fortunately, that’s false. We have many shared characteristics as a people. And “safety” has never been a defining concern of any Americans—whoever they are and whatever their heritage.

The native Americans who were here before European colonization: Were they concerned with safety above all else? Many tribes were seasonally nomadic in response to the various abuses and calamities inflicted by nature. Other tribes maintained great warrior traditions. In their time, “war” was not a matter of pressing a button from the safety of a remote computer, as it is today. It was a noble, hand-to-hand test of strength and courage on behalf of your community. When the Europeans arrived, the native people fought valiantly and doggedly to save their families, homes, and way of life from a powerful and technologically superior foe. These are not the behaviors of people consumed with worry about “safety.”

The early European colonists to America did not sail across the ocean because they wanted to kill Indians. And most didn’t undertake such a dangerous journey because they expected to get rich. Anyone concerned with greater comfort, stability, and even wealth would have been better off staying in Europe in the 17th century. But their monarchs did not allow free practice of religion. The New England colonists were people of such great faith that they would leave their ancestral homes and risk death—including the death of their children—to go on a sea voyage that might end in utter destruction. In the best case scenario, the pilgrims would arrive safely on the shore of an unknown, inhospitable land, where they would need to begin the monumental work of building a new society from the ground up. These are not the behaviors of people paralyzed by fears about “safety.”

What about the African peoples sold into slavery and brought across the ocean in conditions that undermined every shred of human dignity? For centuries, those people endured the inhumanity of chattel slavery: No one can call the condition of the American slave “safe.” Runaways weren’t looking for safety, either. They sought liberty. The journey to freedom could be deadly, and even when it was successful, there was precious little safety to be had in the north: There was hatred and violence toward black people there, too. That’s to say nothing of the risks and hardships they faced in procuring their own food, their own land, and their own work in a new region of the country. And when discrimination and abuse endured for a full century after emancipation, black Americans protested and resisted this treatment, again risking life and limb. These were not people obsessed with “safety.”

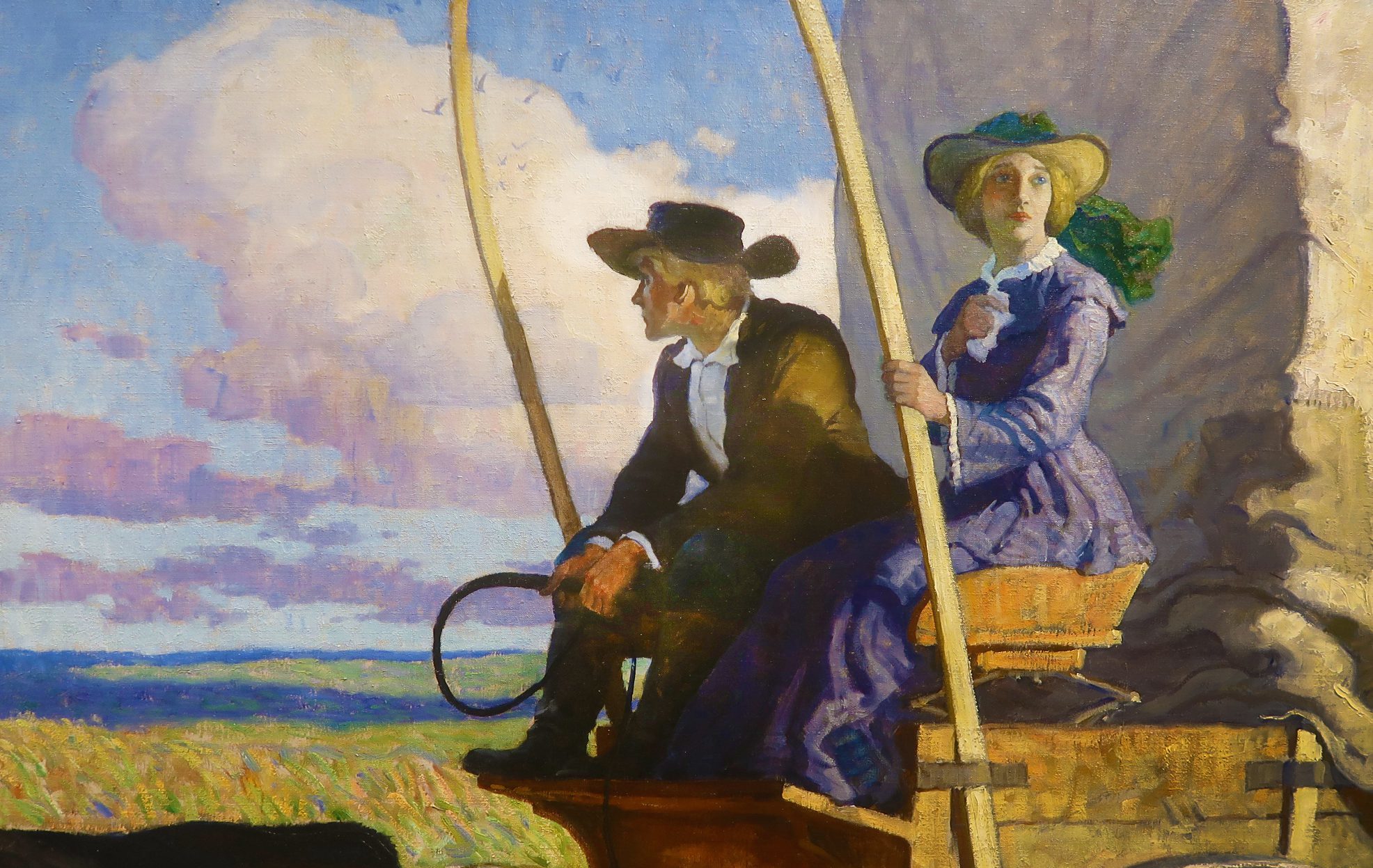

What about the people who pushed further west? The Americans who set out into uncharted lands, crossing the continent in a wagon train at the pace of an ox? They embarked on that trek in full knowledge of the threat of serious illness, of attacks from hostile Indians, of winter so severe that they might simply freeze or starve to death along the way. They took these risks on the assumption that they were heading west to a better place—not a safer place, but one with a greater promise of human flourishing. The same can be said of the Asians who came to a land with a tongue that couldn’t be more different from their own, but who nevertheless thrived even as they worked to exhaustion building a network of railroads.

The great waves of immigrants who came from Europe in the 19th century? Those people were not coming here for entitlements: Unlike today, there were no promises of debt forgiveness, or free schooling, or worker’s compensation, or welfare payments, or universal health care. They left their families and homes for the possibility of prosperity and liberty. They got on the boats with the understanding that securing these benefits would depend on their own effort and hard work. They knew it wouldn’t be “safe.” But they weren’t looking for safety.

We were the first nation to send people to the moon. We have more turnover in our upper class than most countries the world over. Fortunes are lost and made and lost again in the pursuit of innovation and progress. That’s not what happens to people who play it safe. The actions of the everyday Americans aboard Flight 93 on September 11, 2001, saved countless lives on the ground. Storming a cockpit full of murderous terrorists is not the behavior of people preoccupied with safety.

The American character is defined by three things that unite all the different groups of people who make up our nation: mobility, risk-taking, and optimism. We’re movers and we always have been. A fearful people do not move the way Americans do. Safety demands that we take cover—that we stay in one place. But we keep moving. Even in our darkest times, we maintain our optimism. That optimism is evidenced by our risk-taking: People who believe that things can’t or won’t get better don’t make the calculated risks that Americans make.

All of this begs the question: Are we still the same people as we were? Are we still a mobile people with hope for the future? People who live our lives as though we are masters of circumstance rather than its victims?

Quarantines and lockdowns, especially for a virus as commonly survivable as Covid-19, are decidedly un-American. They undermine our natural inclinations for mobility and free movement. The idea that everyone must take an unproven, fast-tracked vaccine, not merely for their own safety, but for the safety of others, is one more manifestation of this monomania. Required masking continues, despite the limited evidence that cloth masks reduce transmission in any significant way. One cannot deny the absurdity of regulations that ask restaurant patrons to cover their faces long enough to walk to a table, only to unmask after being seated. The demand for vaccine boosters represents a whole new level of fear over safety. The vaccine offers great protection, we are told. It is, of course, “safe and effective”—but not effective enough to live your life without fear, in a way that becomes the American spirit. Better get another booster. Just to be safe.

We are now entering our third year of pandemic insanity. Many of the measures that were taken in early 2020 were justifiable because we faced a novel virus about which we knew very little. We can no longer claim that kind of ignorance. Covid-19, generally speaking, is not a deadly virus. Nevertheless, we have sacrificed immensely to try to keep Americans safe. We have done the lockdowns. We have done the masking. We have done the contact-tracing. We have done the double-masking. We have done the vaccines. We have done the boosters. We have done the public shaming. We have asked people for their papers. We have made their employers comply. We’ve done it all. And Covid is still here. The fact is, it will always be here. Covid won. But we don’t have to become a defeated people.

The question now is how we will respond. Will we be Americans worthy of the name? Or will we live in fear, compromising everything—indeed, compromising who we are—to ensure that everyone is just a little safer? Are we willing to make those sacrifices? Are we willing to demand them of our children? For how much longer? And for how long will we allow our government to make such decisions for us?

Americans must now make a choice. It’s not merely a choice about how we want to live. It’s a choice about who we want to be. Those who fetishize safety posture themselves as virtuous people; they pretend that their concerns are an expression of a deep, abiding care for others. But this is a lie. Ultimately, safetyism—where the avoidance of harm becomes a way of inhabiting the world—is a radical form of self-regard. To elevate safety to the status of an idol reveals a fear of life; it conceals a pathological mindset where worry and uncertainty become a controlling presence. It is solipsistic navel-gazing, a decadent wallowing in anxiety and self-pity.

The dehumanizing aspects of safetyism are disguised by endless platitudes about the well-being of others. But insisting upon others’ compliance so that you can live a safer life (after all, we can never be entirely safe) is ultimately an expression of personal weakness. It is a betrayal of the national character. Taken to the scale of society at large, safetyism threatens the dignity of our people. The time has come for a collective embrace of risk—the inherent risk that is the price of freedom in an uncertain world. The time has come to reclaim our dignity, to become again who we are—and who Americans have always been. Safety third.

Adam Ellwanger is a professor of English at the University of Houston-Downtown. He is the author of Metanoia: Rhetoric, Authenticity, and the Transformation of the Self, available in paperback this April. You can follow him on Twitter @DoctorEllwanger.

Comments