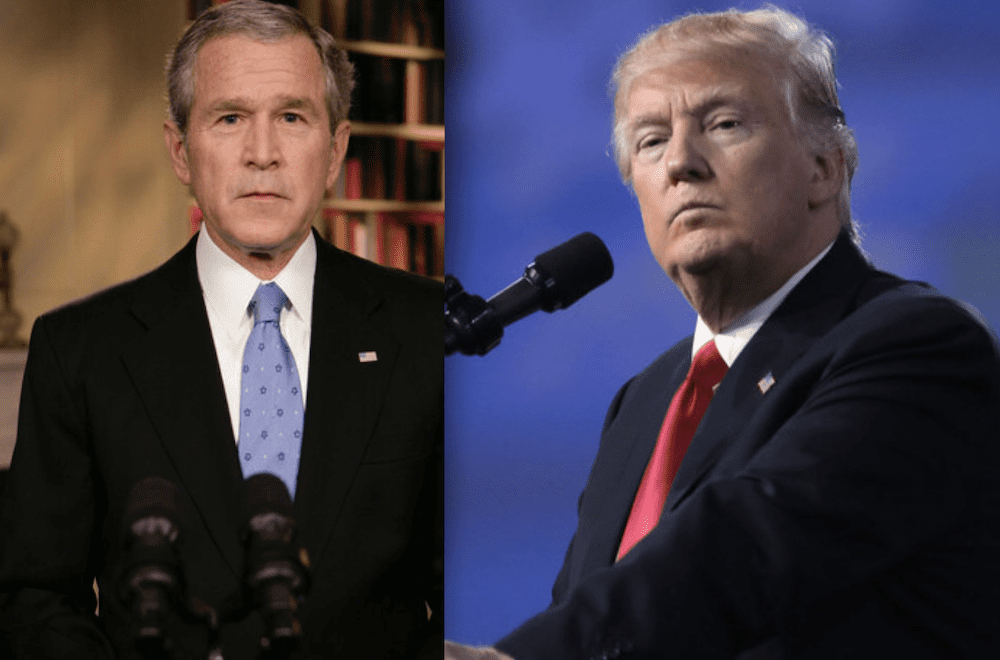

On Iraq, is Donald J. Trump Morphing Into George W. Bush?

One could be forgiven for thinking that Donald Trump had morphed into George W. Bush. The U.S. military is occupying Iraq. American forces are fighting and killing Iraqis. And Washington refuses to withdraw.

Last week, Iraqis, allied with but not controlled by Iran, attacked a U.S. base. The administration retaliated. Two days later, antagonists, unknown but suspected, launched another assault. A third rocket volley hit earlier this week. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo vowed to strike back “as necessary,” which could mean every couple days.

Iraq has become a transmission belt of conflict. That’s why it’s time for American troops to leave. Now.

Invading Iraq was one of the worst foreign policy decisions any president has ever made. Withdrawing American forces in December 2011 was one of the best. A continued U.S. presence would not have stabilized Iraq. Rather, disparate Iraqi factions would have united in opposition. Shia groups like the Mahdi Army, led by radical cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, would have joined Sunnis, including ISIS, in targeting Americans. With U.S. backing, the Baghdad government would have had even less incentive to moderate its sectarian policies.

Unfortunately, America’s exit lasted only until June 2014, when the Obama administration ordered the troops back. The Islamic State was brutal but posed no direct threat to America—the group was focused on creating a caliphate, or quasi-nation state, not conducting terrorism against faraway ideological foes, as was al-Qaeda. Nor was U.S. assistance mandatory. The organization was opposed by every government in the region. Washington’s entry allowed other nations to shed their responsibilities.

Baghdad declared victory over the Islamic State in December 2017; ISIS lost its last territory a year ago. It remains a dangerous idea, but it can be contained by other states. The U.S. need not stick around forever. With American forces starting to pull back, a Washington official admitted to the Financial Times: “Iraqi national forces were increasingly able to fight ISIS without U.S. support.”

So why are American troops still there? Because the president wants to apply military pressure on Iran. Washington has already declared economic war on Tehran; now it’s threatening Iran militarily, as demonstrated in January when the U.S. assassinated Qasem Soleimani along with several Iraqi officials.

Iraqi politicians could not ignore such an egregious violation of Iraqi sovereignty. Outgoing Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi denounced “an aggression on Iraq as a state, government and people.” Parliament voted to send the 5,200 U.S. service members home. Trump dismissed the criticism, threatening to impose sanctions “if there’s any hostility, that they do anything we think is inappropriate.” In January, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis turned out for what al-Sadr termed a “Million Man March” calling for America’s departure. He urged the U.S. to avoid “another war.”

After Soleimani’s death, Iranian-backed forces struck Ain al-Asad Air Base, apparently warning of the impending assault. The president brushed off the incident as causing no casualties, yet 109 service members suffered brain trauma. Tehran had demonstrated its capabilities without triggering another retaliatory round.

Defense Secretary Mark Esper claimed that the administration had “restored a level of deterrence with” the Kataib Hezbollah militia. Yet Esper later dismissed the importance of rocket attacks on Baghdad’s Green Zone, which hosts the U.S. embassy and American troops: “We should have some expectation that the Shia militia groups, either directed or not directed by Iran, will continue in some way, shape or form to try and undermine our presence there, either politically or, you know, take some type of kinetic actions against us or do Lord-knows-what.”

The latter Esper was right. Last week, rockets hit Camp Taji, killing two Americans and one British soldier, and wounding 18 others. Washington then struck a base shared by Kataib Hezbollah (it had praised the Camp Taji attack without taking credit). The U.S. reportedly wounded five militia members without destroying much materiel, while killing five Iraqi security personnel and one civilian.

General Frank McKenzie, commander of U.S. Central Command, said, “We believe that this is going to have an effect on deterring future strikes of this nature.” Pointing to the “enormous” firepower of two nearby aircraft carriers, McKenzie added: “I would caution Iran and its proxies from attempting a response that would endanger U.S. and coalition forces or our partners.”

Then Camp Taji was hit again on Saturday, wounding three allied personnel. McKenzie reversed himself: “I think tensions have actually not gone down. I still think they are actively seeking ways to achieve destabilization that would allow them to escape the strictures of the maximum pressure campaign.” However, Esper continued to talk tough: “You cannot attack and wound American service members and get away with it. We will hold them accountable.”

On Monday, a training facility, Besmaya Base, was attacked, with no report made on possible casualties. Warned Michael Knights of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “Iran’s militia proxies in Iraq can trade empty buildings or even two dozen of their own rank and file for three Anglo-American fatalities all day, every day. This [is] a game we will lose.”

Since October, more than 160 rockets have been unleashed in 25 strikes on the embassy or bases hosting American forces. A new group, the League of the Revolutionaries, claimed responsibility for the latest incident, which might be a tactic to further confuse Washington. McKenzie has already admitted that Iran had only loose control over the Iraqi militias, especially after Soleimani’s death.

Iraqis have focused their ire on the U.S. The government of interim Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi criticized the “violation of national sovereignty” and denied “that the American forces or others [can] take any action without the approval of the Iraqi government and the commander in chief of the armed forces.” The statement added: “This necessitates the speedy implementation of the parliament’s decision on the issue of the coalition’s withdrawal.” Foreign Minister Mohamad al-Hakim summoned the U.S. ambassador to denounce “the recent American aggression.”

More ominously, the U.S. antagonized the Iraqi military. The Iraqi Joint Operations Command called the U.S. attack “treacherous,” “an aggression,” one that “cost the lives of Iraqi fighters while they were doing their military duty,” and a violation of “Iraqi sovereignty and in contrary with principles of cooperation and alliance between Iraqi security forces and US forces.” It endorsed the parliamentary demand for America’s departure.

Most Iraqis don’t want to be stuck between two nominal allies. Said Iraqi President Barham Salih, “Iraq must not be a battleground for other countries to settle their disputes.” Still, Iran has the decided advantage, especially given its permanent location next door.

After the latest round of attacks, the administration revealed plans to move troops from three smaller installations and upgrade base defenses. These are but palliatives, concentrating targets in slightly better protected facilities—for instance, Patriot missiles only work against long-range missiles—and reinforcing the look of permanence at facilities the Iraqis have ordered to be emptied.

Knight proposed going all in, hitting “high-value leadership targets” whenever possible and bringing additional “force protection assets into Iraq…without further consultation with an Iraqi government that would rather adopt a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ approach.” However, even that might not deter militia retaliation and would antagonize Iraqis.

Opposition to America’s presence already runs deep, exacerbated by its ostentatious violation of Iraqi sovereignty. Sajad Jiyad, of Baghdad’s Al-Bayan Center, warned, “Our politics has also taken on a strong anti-American voice.” Al-Sadr is campaigning against Washington’s presence. Additional U.S. strikes would only encourage other factions to mix business and pleasure, as it were, and send government officials running for political cover.

The best reason for America to leave is that there is no good reason to stay. The Middle East no longer matters that much. Oil production has diversified (and Saudi Arabia currently is driving prices down). Israel is secure, a regional hegemon. Iran is weak, unable to threaten distant America and surrounded by enemies.

ISIS has been defeated as a caliphate, or nation state. Last week, two members of a Marine Special Operations team died and four others were wounded fighting Islamic State members. Yet the group’s remnants can be contained by others: Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, and the Gulf States backed by Russia and Europe. With American forces under fire in Iraq, a Washington official admitted to the Financial Times: “Iraqi national forces were increasingly able to fight ISIS without U.S. support.”

Finally, the U.S. is essentially bankrupt. Washington is running a trillion dollar deficit; officials are considering a $1 trillion fiscal stimulus to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Washington should stop wasting money on fruitless forever wars in the Middle East, which have already cost $6.4 trillion.

“Eventually we want to be able to let Iraq run its own affairs,” the president said in January, but “this isn’t the right point.” That should be Iraq’s decision. The time to leave is now, before more Americans die in Iraq for no good purpose.

Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. He is a former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan and author of several books, including Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.