Foreigner and Fascist: Malaparte in Paris

Diary of a Foreigner in Paris, Curzio Malaparte, NYRB Classics, May 2020, 288 pages

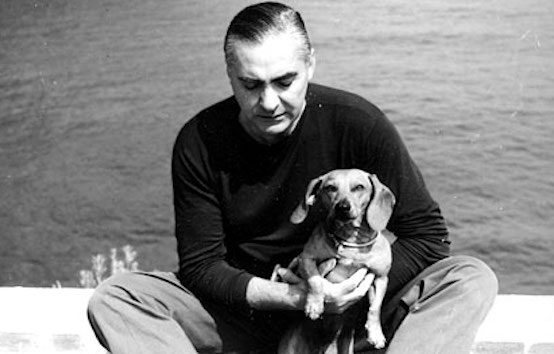

In a century when so many intellectuals made the leap from communism to the Right, Curzio Malaparte was one of the few who traveled in the opposite direction. Born in 1898, he was a wunderkind of Italian fascism in his twenties, haunting the cafes of Florence with Filippo Marinetti and the Futurists and taking part in Mussolini’s March on Rome at the age of 24. His career as a fascist intellectual peaked in the early 1930s as he tried to push Mussolini in a more populist direction from the editor’s chair of various periodicals, including the daily La Stampa. World War II put a seal on a decade of gradual disillusionment, and by the time of his death in 1957, Malaparte had become such an enthusiastic Maoist that he left his house in Capri to the Chinese people for use as an artists’ colony.

The last place someone with Malaparte’s past would want to be, one would think, was Paris in 1947. The Épuration was in full swing. Robert Brasillach had recently been tried and executed and Charles Maurras sentenced to life in prison, proving that even writers could be punished for crimes of collaboration. Yet Malaparte was drawn to the city despite the risks, and in his two years there he managed to produce two plays for the Paris stage, write at least one book, and meet such luminaries as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Cocteau, and André Malraux.

Unsurprisingly, the luminaries greeted him coldly. Diary of a Foreigner in Paris, published this month by NYRB Classics, records a scathing dinner party encounter with Albert Camus, who fixes Malaparte with a death stare from the moment he walks in. Another guest asks Malaparte to give his opinion of one of Mussolini’s former cabinet ministers. “Camus, without looking at me, replied that all these men, assassins, etc., should be shot.” Malaparte shrugs off the insult as a young man trying “to give himself the air of a Saint-Just,” but can’t resist describing for the reader an elaborate fantasy scene where Camus points a rifle at his blindfolded head in a one-man firing squad—and misses.

The left-wing intellectuals’ contempt for Malaparte was amply returned. “I wonder what the hell Camus ever did to have the right to shoot others,” Malaparte scoffs. He dismisses Sartre as a man of postures rather than ideas, and not even good postures at that. “It seems to me excessive to trouble Kierkegaard, Jaspers, and Heidegger, the concepts of angst and existence, to justify an entire generation of misfits who are not pederasts but pretend to be, who are not poor but pretend to be, who are not bohemian but pretend to be,” he sneers.

The Parisians seemed to him like creatures of fashion, and Malaparte was the opposite of fashionable. He was a true contrarian. All of his ideological gyrations, otherwise so baffling and self-contradictory, can be explained by that. How else to make sense of spending an entire career as an anti-communist only to turn into a Soviet sympathizer in the 1950s, of all decades? Malaparte admits his willful perversity in the Diary. “I believe in noble sentiments only before they become rhetoric,” he writes.

If it seemed to me right to fight the Germans and the Fascists when they were powerful, today I cannot bear the rhetoric that has been made of the struggle against the Fascists and the Germans. Above all I disdain those who have turned their participation in that struggle into a profitable occupation, and the sole reason for their existence.

This claim to have struggled against fascism, which he repeats often in his Paris diary for obvious reasons, is not quite the whole truth. True, Mussolini exiled Malaparte to Capri for sedition in 1933, but that was more of a factional squabble than genuine rebellion. True, the Gestapo kicked him out of the Ukraine in 1941 for writing about German atrocities in the Corriere della Serra, but Mussolini quickly rescued him and reassigned him to cover the war in Finland. Malaparte would not have been welcomed in 1942 as an honored guest at the diplomatic court of Hans Frank, Nazi governor-general of Poland, if he had not been a fascist in good standing.

Malaparte was a chronic embellisher, and not only when political self-interest demanded it. His two best works, Kaputt and The Skin, are thinly fictionalized versions of his war experiences in Nazi-occupied Europe and Allied-occupied Naples, respectively. The books’ power to mesmerize lies in their surrealistic flourishes: a lake in Finland where half-submerged horses lay trapped in grotesque attitudes after a flash freeze; the dictator of Croatia offering Malaparte a basket of human eyeballs, calling them “Dalmatian oysters”; an American officers’ dinner in Naples where guests feast on the choicest fruits de mer from the local aquarium, including manatee.

But Malaparte should not be dismissed as a mere fabulist. For one thing, his varied career did take him to all the places he wrote about. He really was in Jassy the night of the 1941 pogrom, as he describes in Kaputt. He did not invent stories from whole cloth. For another thing, wartime Europe was a more surreal place than the modern reader may appreciate. American officers really did eat the tropical fish out of the Naples aquarium; fresh fish were unavailable because the harbor was mined and boats weren’t allowed out.

When the Germans invaded Budapest in 1944, an Italian fascist diplomat named Giorgio Perlasco pretended to be “Jorge” the Spanish consul and, with the help of stolen embassy stamps and the passable Spanish he had picked up fighting for Franco in the 1930s, manufactured exit visas for thousands of escaping Jews. Malaparte’s war experience was less unique than one might think, both in its bizarre spectacles and in his willingness to resist the Nazis despite being a fascist himself.

Diary of a Foreigner in Paris is neither as surreal nor as satisfying as Kaputt and The Skin. It is disappointing in much the same way as Ernst Jünger’s Paris diaries, also recently translated into English after decades out of print. When A German Officer in Occupied Paris: The War Journals 1941–1945 was published last year, American readers searched it eagerly for insights into Jünger, that most intellectual of fascists, whose aristocratic dignity always stood in such contrast to Hitler’s rabble. Alas, there was none to be found.

Jünger, like Malaparte, met with the cream of Parisian artists and intellectuals, from Pablo Picasso to Sacha Guitry, and like Malaparte he was the rare fascist intelligent enough to converse with them as an equal. But a wall of suspicion remained. Even with all the incentives of occupation urging the French to make Jünger feel welcome, they gave him little beyond superficial chit chat. Whatever maelstrom of emotion these Frenchmen were feeling, they were not about to reveal to a German. This barrier of reserve remained after the war, and Malaparte, for all his social butterflying, never managed to break through it.

At one point in the Diary, Malaparte is introduced to Henriette Caillaux, the notorious murderess who shot the editor of Le Figaro in 1914 over the paper’s repeated slanders of her husband, finance minister Joseph Caillaux. The now aged Madame Caillaux does not extend her hand when they meet, and Malaparte deduces that it is because “assassins are always afraid that people will refuse to shake a hand that has killed.” He is so convinced that his own hands are clean that he never quite grasps that Frenchmen, too, might be particular about the hands they shake.

Helen Andrews is a senior editor at The American Conservative.

Comments