Does Leon Wieseltier’s ‘We’ Include You?

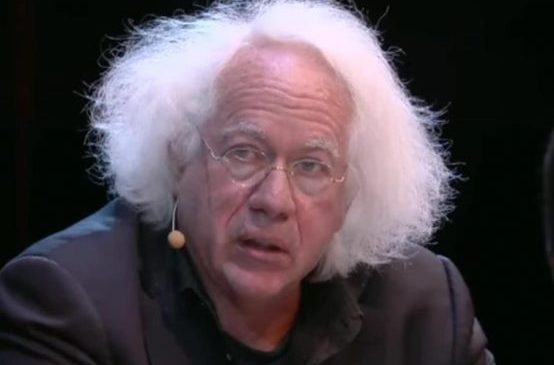

Let no one charge Leon Wieseltier with flinching from what needs to be done. Writing in Liberties, the quarterly that he recently founded and edits, the aging literary lion, his previously exalted reputation today somewhat tarnished, once more summons his countrymen to take up their assigned post. Summons does not do justice to the authority that his writing conveys. Wieseltier instructs, insists, demands, orders. Humankind needs saving. That’s America’s job and we have fallen down on it.

The second person plural is Wieseltier’s preferred mode of expression. From his perch atop Mount Olympus, he speaks to and on behalf of all Americans. Throughout his essay, the we’s accumulate like cicada carcasses. Over the past dozen years, he charges, “We have been living contentedly… in this springtime for Hitlers.” The U.S. failure to intervene in the Syrian civil war draws his particular ire: “We chose to stand idly by, feeling bad and watching it.” As a consequence, “we were disgusting.” American timidity infuriates him. “Right now,” he writes, “we are hardly in danger of doing too much. This has been a golden age of too little.” As a consequence, “we are miserable,” with action the only antidote to misery: “We can be big in the world by doing good in the world. Lacking bigness or goodness, we (and not only we) are doomed.” Nor is there any time to lose. “Soon, if we do not recover our sense of our historical role,” we will find ourselves taking a back seat to China.

The remedy is clear: “America in full, unafraid of history’s pace, unembarrassed by its enthusiasm for democracy and human rights, larger than its mistakes and its crimes, comfortable with the assertion of its power in its own defense and in the defense of others, inspired by the memory of its magnitude, repelled by the rumors of its decline” needs to get back to work tout suite. Cue the National Anthem.

Let me admit to my personal inability to discern “history’s pace.” As for deciphering the “memory” of America’s “magnitude,” I’ll leave that to journalistic hucksters like Henry Luce, who coined the pernicious phrase “American Century.” And when it comes to American decline, it’s not “rumors” that bother me but certain undeniable facts: gaping inequality, internal division, political dysfunction, institutional incompetence, fiscal disarray, and a sequence of grotesquely mismanaged wars.

Wieseltier has little time for facts, much preferring self-indulgent exhortation. His long essay contains not a single piece of data. The approach has its advantages, enabling him, for example, to offer glib judgments such as this one: “I have no doubt that the costs of American action in Iraq have been much less than the costs of American inaction in Syria”—an opinion proffered without either tallying up the Iraq War’s cumulative costs or considering who ended up footing the bill. Hint: it was not Wieseltier’s privileged cohort of the American “we.”

If the Iraq War gets short shrift, the even longer war in Afghanistan qualifies for only a single passing mention. Yet, surely these two protracted conflicts—Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom—deserve recognition as instances when “we” set out to do “good.” How to explain Wieseltier’s lack of interest in exploring why the outcomes achieved have been so disappointing?

Intellectual dishonesty offers one likely explanation. After all, he writes, “The prophetic feeling is a nice feeling, especially in a land where prophets pay no price.” As a self-assigned prophet who vents at great length while leaving others to worry about the price, Wieseltier is no doubt familiar with that nice feeling. As his impassioned homily appears in print, even if only in his own magazine, one can imagine him bathing in it.

That said, Liberties exercises no discernible influence in policy circles. Neither does its editor. Wieseltier exerts himself to convey a contrary impression, alluding to “friends who wanted to talk with me on the way to an appointment at the White House.” As a practical matter, he wields about as much clout as one of Donald Trump’s discarded national security advisers—Michael Flynn, say, or John Bolton.

His bleating merits our attention for one reason only: it reminds us of the post-Cold War hubris that raised havoc abroad and helped to pave the way for Trumpism at home. Eager even today to use force with expectations of thereby doing “good,” Wieseltier remains an unapologetic proponent of moralistic militarism. While at least some militarists have had the good grace to recant or fall silent, he remains steadfast. On that score, he is not alone.

Wieseltier decries what he refers to as this nation’s “choice to abdicate global preeminence and to withdraw from decisive historical action.” In fact, illusions that military mastery empowered the United States to undertake decisive historical action in response to 9/11 demolished any U.S. pretensions to global preeminence. Wieseltier partook in those illusions and remains in their grip. He has learned nothing.

“Where are the Americans?” This is the title that Wieseltier chose to introduce his essay. A plausible answer: trying to find themselves.

In that vein, allow me to suggest that a far more fundamental question demands priority attention: “What have we become?” Unless Americans find a way to reunify their polity and renew their Republic, they may discover that no real “we” exists. In that case, a loss of global preeminence may rank as the least of our problems.

Andrew J. Bacevich is president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. His most recent book is After the Apocalypse: America’s Role in a World Transformed.