Cormac McCarthy’s Conservative Pessimism

Who is the top conservative novelist today? One name that comes to mind is Michel Houellebecq, recently included by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat on the syllabus for his Yale University class on conservatism. And while Houellebecq’s books offer interesting ideas on metaphysics, Islam in Europe, and how the market impacts our love lives, if the right is going to allow nihilistic novels of sexual depravity into its canon, there is a stronger author out there.

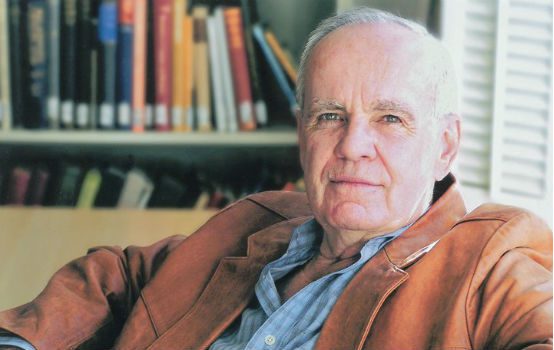

Cormac McCarthy is the greatest living novelist. It’s actually strange that he and Houellebecq aren’t compared more often since both write from a similar worldview about similar topics. Neither is necessarily conservative but both represent well the “cultural pessimism” portion of the Right. And only by grasping why McCarthy is the superior writer can we see see the proper way this slice of conservatism should be integrated into the larger canon.

Conservative interest in Houellebecq stems from his criticisms of European liberalism, particularly his ideas on social isolation, the sexual revolution, and Islam. These are most clearly articulated in his novels The Elementary Particles and Submission. Houellebecq traces Europe’s cultural ennui to empiricist metaphysics that reduce the world to matter. He describes the sexual revolution of the ’60s and Europe’s recent embrace of Islam as symptoms of this disease.

In Elementary Particles, he sneers at the hippie “free love” element of the ’60s and describes how the sexual revolution represented the intrusion of market principles into human relations. According to Houellebecq, hookup culture is a competitive commodity market that breeds the same inequality seen in global capitalism. Submission recasts bleeding-heart platitudes about diversity and Islam as the apathetic shrug of a people deracinated from authentic culture. Though he once called Islam the world’s stupidest religion, his real target is the West’s cultural ennervation. Houellebecq’s pessimism will appeal to conservatives concerned with the future of the West.

Yet above and beyond those ideas, Houellebecq is interested primarily in Houellebecq. A close examination of his choices as a writer reveal the egotistical aspects of his imagination, which undermine his view of cultural pessimism. All of his protagonists are versions of himself; sometimes they even share his name. A certain amount of autobiography is permissible in novels, but Houellebecq’s self-obsession derails the form and structure of his art. For example, in the fourth chapter of Elementary Particles, the third-person narrative inexplicably switches to first person for a single sentence. This is amateur writing. Houellebecq also likes to plod away from the story to deliver streams of sexually explicit details. Occasionally this results in pitch black comedy, but more often it comes across as trying too hard to shock the pearl clutchers.

In Elementary Particles, this sloppy writing is covered up with a narrative structure designed to entice the reader. The protagonist is a scientist who has invented something that changed mankind, though we’re not told what, a tune-in-next-week tease that drags the reader through Houellebecq’s musings. But this is a gimmick, not a story. If Houellebecq were to place his art above his ego, he might wonder whether there was a contradiction in using the storytelling technique of mass-produced entertainment in order to interest readers in his criticisms of mass-produced entertainment. This lack of artistic vigor undermines his portrayal of a lack of vigor in the West, and the absolute pessimism is belied by the palpable joy Houellebecq takes in his provocations.

On the other hand, Cormac McCarthy seems genuinely anguished by his pessimism. McCarthy writes about murderers, scalp hunters, hobos with sacks full of bats, and cannibals. These nightmares are accompanied by Dostoevskian questions over the existence of God and the nature of evil. Not exactly cheery stuff. Like Houellebecq, McCarthy is interested in the aftereffects of the Enlightenment’s metaphysical revolution, and he also casts doubt on the liberal project. But whereas in Houellebecq these ideas are tied together with egoism, with McCarthy they fall within an artistic vision. McCarthy’s primary interest is the limits of language, and his commitment to exploring them forces him to transcend the unrelenting darkness of his novels.

McCarthy wrote an essay on the origins of language where he asserted that our unconscious mind is the part of our consciousness that does not have access to language. His novels consistently link religion and hope with that which cannot be put into words. His play The Sunset Limited is about an evangelical ex-convict who tries to stop an atheistic college professor from committing suicide. When the ex-convict fails, he asks God, “If you wanted me to help him how come you didn’t give me the words?” At the end of Blood Meridian, the protagonist leaves the evil gang of scalp hunters and begins to carry around a Bible, but he is illiterate. This thread runs through McCarthy’s pessimism, carving out quiet hope.

Like Elementary Particles, McCarthy’s Child of God explores themes of isolation and the individual versus the community. The story introduces Lester Ballard as a “Child of God much like yourself.” Then Ballard is kicked off his family farm, lives alone in the woods, descends into insanity, and becomes a serial-killing necrophiliac. The story slyly examines the fundamental liberal myth of the emancipated individual. McCarthy intersperses Lester’s downfall with monologues by various townspeople trying to come up with explanations for the monster. The juxtaposition is shadowed by McCarthy’s introduction, and so our attention is drawn to the insufficiency of materialistic explanations. What is said, and left unsaid, leads us to question the role the community played in creating Lester. Thus did McCarthy diagnose and examine the Sandy Hook killer, the Toronto incel terrorist, and the age of isolation all the way back in 1973. Despite the bleakness, Child of God ends with Lester surrendering himself to an insane asylum with the words “I belong here.”

After Child of God, all of McCarthy’s novels end with room for hope. Suttree follows a nihilistic vagrant on Huckleberry Finn-like adventures, but ends with the protagonist making a fresh start. Blood Meridian is the overwhelmingly violent tale of a scalp-hunting gang, but it ends with the vague dawn of civilization. This career trajectory found it’s apotheosis with The Road, McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a father and son in a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It’s probably the McCarthy work with which conservatives are most familiar. McCarthy unequivocally releases the warmth and tenderness missing from most of his work, and equates hope with what is passed from one generation to the next. Among the works of both Houellebecq and McCarthy, The Road is both the most explicitly conservative and explicitly hopeful. This is because McCarthy pursued a vision, rather than an ego.

Houellebecq’s writing demonstrates that near-constant pessimism is often accompanied by a yawning egoism. As Milton’s Satan tells us, the mind can make a heaven out of hell. Too often, conservatism reeks of such self-indulgent pessimism. It is unreflectively repeated that conservatives have a “tragic view” of man, but this is different than enjoying tragedy. Dour cultural predictions are easily aestheticized, and Houellebecq is essentially a romantic. Cormac McCarthy should be placed higher on right-wing reading lists because his artistic vigor demands a vision of hope.

I want to end by suggesting that if Houellebecq’s Submission offers the self-indulgent view of European liberalism’s inevitable end, then McCarthy’s “Border Trilogy”—about cowboys on the border of Mexico just as technology begins to erase rancher culture—offers the obstreperous American rebuttal. Cormac McCarthy is important to the conservative canon because in his bleakness he reaffirms that a conception of evil necessitates a conception of good, and that a tragic vision necessitates a vision of joy.

James McElroy is a New York City-based novelist and essayist, who also works in finance.

Comments