168 Days: Recalling an Old-Fashioned Court Packing Drama

The last time anyone sought to “pack” the Supreme Court, that hallowed independent branch of government was in the hands of conservatives imbued with the imperative of maintaining a strict construction of the Constitution.

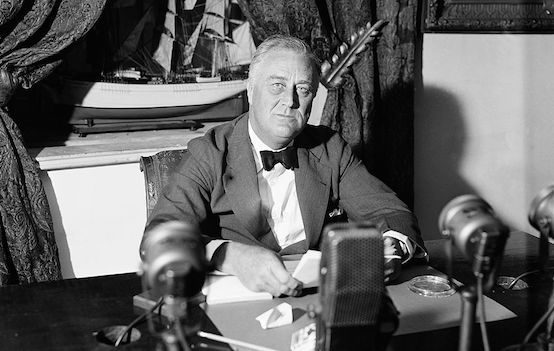

That rankled Franklin Roosevelt, who got his big and innovative agenda through Congress with ease, only to have major elements of it nullified as unconstitutional. By 1937, the court had struck down nine out of the 11 major New Deal initiatives, leaving intact only the Tennessee Valley Authority and the devaluation of the dollar.

The ensuing battle, in which Roosevelt sought to remake the court to render it more hospitable to his thinking, consumed American politics for 168 days. Ultimately the president lost. He had overstepped and the political system slapped him down.

That episode from long ago may be instructive in our time. Leading liberal Democrats are once again contemplating initiatives to remake the Court, not through the normal course of nominations and confirmations but through a maneuver to alter suddenly the political balance of power in the country.

Back in 1937, FDR feared for the fate of major foundations of his bold agenda, including Social Security, the Wagner collective bargaining law, and the Utilities Holding Company Act. All were working their way up for judicial tests, and Roosevelt knew the court could very well strike them down too. He decided he had to do something about it. He had to remake the court.

And why not? In the wake of the 1936 elections, he stood at the pinnacle of his power. He had won reelection with nearly 61 percent of the popular canvas and an Electoral College tally of 523 to eight. The opposition Republicans held only 17 seats in the Senate and 89 in the House (to 333 for the Democrats). As journalists Joseph Alsop and Turner Catledge wrote in The 168 Days, their book on the subsequent political battle, “Who was there to say him nay?”

Politically emboldened, FDR came up with a simple solution. He would foster legislation that allowed him to appoint a new justice, up to a total of 15, for every sitting justice who refused to retire at full pay within six months of reaching age 70. This was enough power to remake the court, given the justices’ ages. Six of the nine justices were 70 or older.

When Roosevelt unveiled his plan on February 5, 1937, first to aghast members of Congress and then to reporters, he invited a political struggle far beyond anything he had anticipated. What followed were months of political maneuvering, intrigue, backroom bargaining, and furious oratory as the president pressed his plan with all the force and cunning he could muster. Meanwhile, his opponents, including many Democrats and New Dealers, moved to check his power grab.

When FDR’s chief defender, Senate majority leader Joe Robinson, died in his bed of a heart attack, the president’s court packing scheme died with him.

Capturing the drama, Alsop and Catledge shaped the story into a kind of Greek drama, with the president cast as the hero of the realm brought down by his own arrogance. “Suddenly,” they wrote, “ the old Greek Theme of Hubris and Ara, of Pride and the fall that comes after, dominated the play.”

And yet soon afterward it all seemed an unnecessary spectacle, because enough of the justices departed the bench the routine way to allow Roosevelt to recast the court. And then began a new era in American judicial history, one of court liberalism when judicial activism reigned in a host of areas. Roosevelt’s New Deal emerged as a powerful altering force in American politics.

This era reached its flowering during the tenure of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who headed the court from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court demonstrated its activist sensibility chiefly in the areas of civil rights, civil liberties, judicial power, and federal power. Conservative writer Brent Bozell captured the era in the title of his 1967 book, The Warren Revolution.

This era came to an end with court nominations put forth by subsequent Republican presidents, notably Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. But Nixon had two conservative court nominees from the South rejected before settling on the centrist Harry Blackmun. And some Republican court appointees turned out to be less conservative than anticipated. The result was that the court entered an era of relative political balance, with “swing vote” power wielded by Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy. During this time, major decisions were handed down by both liberals and conservatives.

Now it seems the court is heading into a new conservative era, with a slim right-leaning majority of Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh. But Roberts seems more interested in maintaining the court’s standing in the eyes of the American people than in any political ideology, and he could emerge as its next swing vote.

In any event, this brief history, starting with the conservative court that so rankled Franklin Roosevelt, demonstrates that the American republic has survived these swings in the court’s general political outlook. Roosevelt ultimately got the court he wanted even after his blatant power grab was thwarted. The Warren court’s lurch to the left ultimately was leavened by a more centrist judicial sensibility. And now a conservative court might be just what’s needed to check the burgeoning power of the executive branch and the unelected managerial mandarins of the government and to thwart the judicial activism of the lower federal courts.

Many liberals, including some of the announced or putative Democratic candidates for president, have been flirting with the idea of a new court packing scheme of their own. They want to expand the court to 15 members and give the next (presumably Democratic) president a chance to remake it outside the normal course of presidential nominations.

Good luck with that. The American people don’t like that kind of raw power maneuver, as FDR discovered to his chagrin. Any presidential candidate who pushes too hard on this issue will live to regret it, as will any president who seeks to succeed where Franklin Roosevelt, at the height of his influence, so abjectly failed.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington journalist and publishing executive, is the author most recently of President McKinley: Architect of the American Century.

Comments