Making Sense of American-Made and Fueled Bombs in Yemen

Between 60,000 and 80,000 innocents have died in the Saudi-led war in Yemen that began in 2015. And another 14 million Yemenis are at risk of death from disease and starvation caused by the destruction of infrastructure and a blockade-induced famine.

Throughout the war, starting with President Barack Obama and continuing under President Donald Trump, Washington has provided refueling, targeting intelligence, and many of the bombs used by Saudi Arabia and its coalition partner the United Arab Emirates. Yet when both houses of Congress passed a bipartisan bill under the War Powers Act calling for U.S. withdrawal, Trump vetoed it. The Senate was unable to muster the votes to overrule him.

There are no major U.S. interests at stake in Yemen. The sheer number of civilian casualties is unjustified, and will only spawn more anti-American sentiment, especially in the Muslim world. Moreover, we cannot be prepares for renewed great power competition if we keep getting bogged down in endless conflicts with minor powers and regional actors in the Middle East.

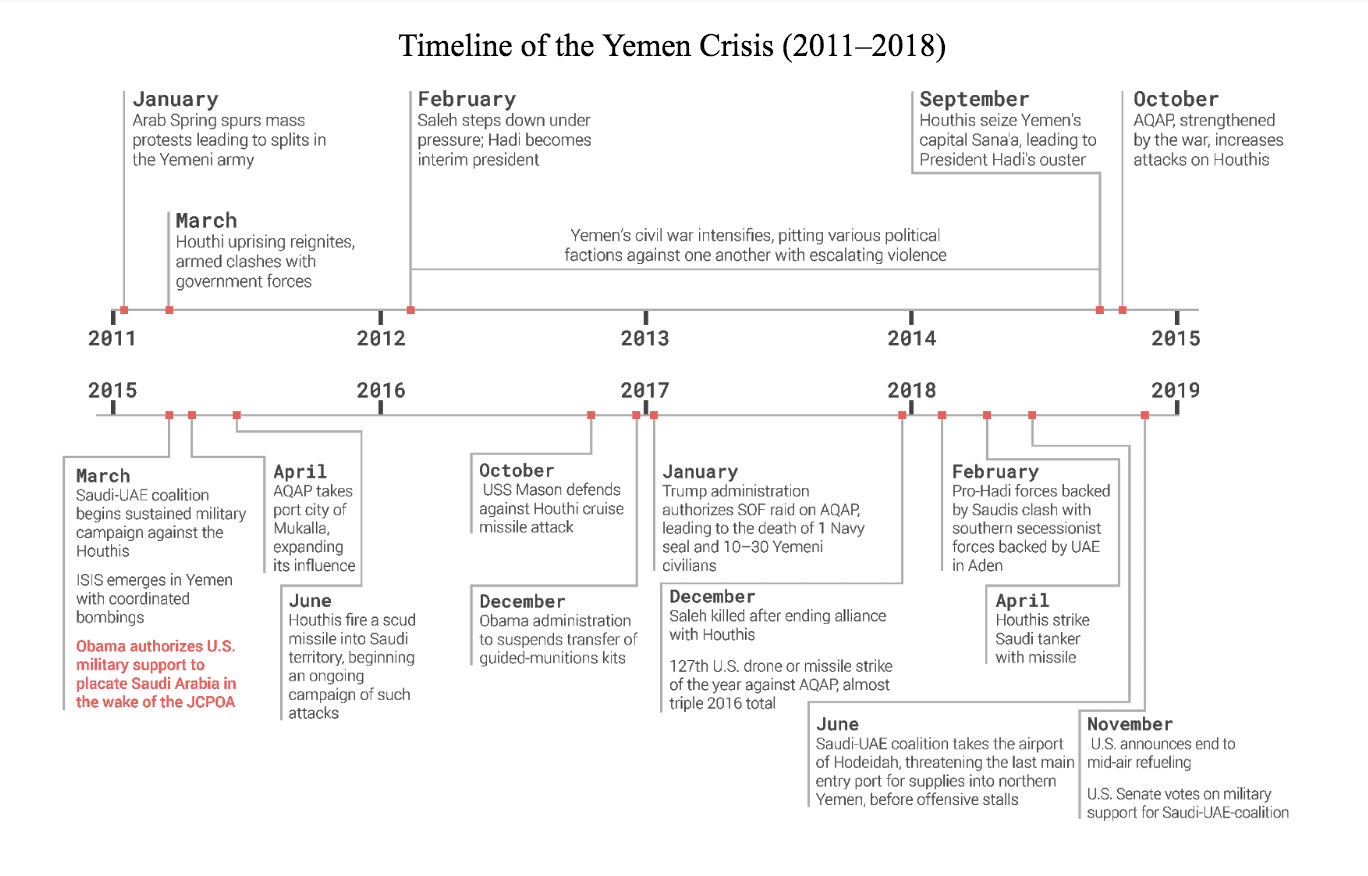

When Houthi rebels seized Yemen’s capital of Sanaa and ousted then-president Hadi in 2014, the United States quickly supported the Saudi-led coalition’s intervention to prevent them from gaining control of the country. Since then, Washington has presided over yet another disastrous war that harms U.S. interests—a reality at odds with Trump’s non-interventionist instincts and campaign promises to end the wars he inherited from his predecessors.

According to the Yemen Data Project, a nonprofit run by academics and human rights advocates, nearly one third of all coalition airstrikes between March 2015 and March 2018 hit civilian targets. These included schools, neighborhoods, mosques, hospitals, food stores, farms, markets, electric grids, and water supplies. For instance, in October 2016, the U.S.-backed coalition bombed a funeral home, killing 155, and in August 2018, a school bus was attacked, killing 40 children and 11 adults. Both strikes used American-made bombs.

The resulting conditions for Yemeni civilians have been catastrophic. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, about three million Yemenis have been forced to flee their homes and are displaced. Furthermore, a little over a million have suffered from an ongoing cholera epidemic.

As much as Washington might like to think its vast arms sales, intelligence sharing, pressure, and longstanding friendship with Riyadh would make a difference in sparing civilian casualties, it hasn’t. As a policy paper published by Defense Priorities points out: “U.S. aerial refueling allows pilots to stay aloft longer and practice ‘dynamic targeting,’ where they hunt for targets of opportunity and likely increase civilian casualties.” If America instead withdrew its full support, including providing spare parts, the Saudi war effort would ground to a halt. Yemen needs humanitarian aid and peace not more bombs. As that paper summarized, “There is no compromise between U.S. security and values there—we are losing on both counts.”

Although both sides of the Yemeni war have committed atrocities, U.S. involvement has only increased the regional harm and chaos. As Yemen spins out of control, anti-American sentiment rises, and every airstrike on civilians and vital facilities becomes a potential recruitment tool for terrorists.

And U.S. military involvement in Yemen has damaged more than just America’s image—it’s also hampered more important strategic goals. The Trump administration’s 2018 National Security Strategy declared that the world had returned to great power competition and that Washington would refocus on deterring state-to-state wars. The policy has not matched the words on that paper. The United States has not done anything to reduce its involvement in the Middle East, a region of limited and diminishing strategic importance for American security and prosperity. Recognizing reality isn’t good enough if a country cannot match its means to its ends.

In this light, our intervention in Yemen is yet another unnecessary, harmful war against third-rate rebels that drains American attention and resources. U.S. policymakers tend to forget that while they are worried about Russia and China, Washington is overstretched, fighting at least five wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen.

All of these conflicts are open-ended, with little to no connection to vital national security, and a misuse of funding that could be better spent elsewhere—from fixing America’s domestic infrastructure to paying down our nation’s $22 trillion national debt.

Finally, these multiple wars ask too much of America’s men and women in uniform. Yemen itself might be primarily an air war for the United States, but it still puts a strain on our forces and budget. U.S. service members would be better served if the government ensured that there is enough personnel, training, and equipment to deter conflicts instead of attempting to fight other countries’ wars for them. Our military should be used to defend America against her enemies, not to referee conflicts or prevent bad guys from killing other bad guys.

This past November, in response to widespread public uproar over the U.S. role in the Yemeni civil war, the Pentagon announced that it had ceased air-to-air refueling support for the Saudi-led coalition. That was a good first step, but it wasn’t enough. American interests demand that we end all U.S. military support for the Saudi-UAE coalition’s costly and atrocity-laden intervention in Yemen’s civil war.

John Dale Grover is a fellow with Defense Priorities and a writer for Young Voices. He is also an assistant managing editor with The National Interest. His articles have appeared in Defense One, Real Clear Defense, The Hill, Fox News, and The American Conservative.