Afghanistan’s Deadly Indecision

One might call Dr. Abdullah Abdullah “always a bridesmaid, never a bride,” now that the former Afghan foreign minister is trailing behind political rival Ashraf Ghani in the preliminary presidential election results this week. But that would indicate a degree of levity in Afghanistan’s political process that just doesn’t exist.

Instead, a protracted stand-off over the winner of the election is deadly serious business, threatening to destroy any chance for a smooth transition of power now that the problematic long-time President Hamid Karzai is finally on his way out, as are we. In fact, if Americans weren’t already war weary and disinterested enough, a power vacuum—or a potential civil war—will only accelerate the calls to get out completely. If that comes to pass, will Afghanistan someday look like Iraq does today?

“This paralysis is critical in a country where the next president will control Afghan forces and almost all Afghan spending. Worse, there is no guarantee of national unity once a decision is made, and less and less incentive for outside powers to provide the support Afghanistan will so desperately need,” Anthony Cordesman, former Department of Defense official and national security expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, tells TAC.

And that support spells billions of dollars in aid, from farming and reconstruction to security and economic development. All that is now at risk if both sides cannot agree on the results of the election by inauguration day Aug. 2, when Karzai’s term officially expires.

Moreover, the U.S is not likely to keep troops there for long if the election leaves a weak leader in charge. This could happen if most Afghans believe the election is not legitimate, like in 2009. At that time, Karzai was blamed for widespread fraud in his own victory over Abdullah. “What you don’t want is what Abdullah said is true—that (this) election was cooked—and then you have what you had in 2009,” offered Larry Korb, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and former Assistant Secretary of Defense.

“That would be the worst outcome,” for both the United States and the Afghans who are embarking on their first independent presidential election without Karzai, who the U.S helped to install in 2001, he told TAC. “If it turns out that’s the case, then it won’t be good in terms of being able to keep the country together to deal with the Taliban. Look at Iraq—Iraq was a rich country, and look what happened there.”

Both Abdullah and Ghani have said they would sign the Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA) that would keep U.S combat troops in Afghanistan beyond the end of this year, which Karzai had refused to sign. There are currently 33,000 American troops there now, but they are slowly coming home. Obama wants to keep close to 10,000 soldiers in Afghanistan until 2016, but a political crisis would certainly hinder those plans.

“Losing U.S. support will leave either presidential victor with the strong possibility that his governance will be untenable,” wrote The Guardian’s Spencer Ackerman on Wednesday.

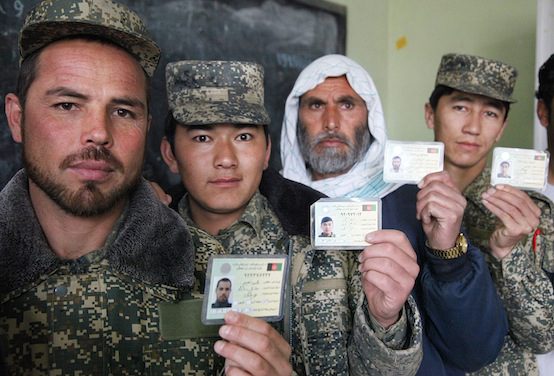

Election Fraud Looms Again

On one side you have Abdullah, 53, who rose to political power as a key figure in the Northern Alliance, which helped the U.S. and its European allies oust the Taliban from Kabul after 9/11. On the other is Ghani, a former World Bank official and darling of the West, who surprised everyone with his huge lead in the run-off election. Abdullah is accusing Ghani and his supporters of inflating his numbers by stuffing ballots in key districts. Before the results were even announced on Monday, Abdullah said he would not concede until all the “clean” votes were separated from the fraudulent ones. Last month, he produced tapes that allegedly exposed an International Election Commission official talking about stuffing ballots in Ghani’s favor.

Abdullah took a similar stance when he dropped out of the 2009 run-off after accusing—rightly, as it turns out—Karzai of widespread fraud. But this time around, he appears unyielding. After it was announced that Ghani was leading in the runoff 56.4 percent to his 43.5 percent, Abdullah called the results a “coup against the peoples’ votes,” and declared his own victory in the election. “You are the victorious; you have won the vote — there is no question,” Abdullah shouted to a cheering crowd in western Kabul, according to Erin Cunningham at the Washington Post. “We would rather be torn into pieces than accept this fraud. We reject these results … and justice will prevail.”

Meanwhile, the BBC’s Karen Allen reported, “People at the venue where Abdullah Abdullah spoke to his supporters were angry. A crowd tore down a poster of outgoing President Hamid Karzai chanting: “Death to Karzai. Long Live Abdullah!” According to a Wall Street Journal report on Wednesday, powerful supporters were already announcing they would only follow a “parallel government” formed by Abdullah (so far Abdullah himself has stopped short of saying that he would create one). “We want to defend our rights in a civilized way. But if it doesn’t work, we will take our weapons again,” said Abdul Wasi, one of Mr. Abdullah’s supporters at his rally. For his part Abdullah has said he does not want “a civil war.”

At the center of the crisis are the IEC and the International Elections Complaints Commission (IECC), who will decide whether they will be conducting a “deep” audit of a million or more votes in the run-off. That there was fraud in the voting is not in dispute. When announcing the results on Tuesday, IEC head Ahmad Yousef Nuristani acknowledged that more than 11,000 ballots had already been tossed as fraudulent, and about 60 percent of those had been cast in favor of Ghani. (The Afghan Analysts Network’s Martine van Bijlert says that overall number is implausibly low considering the record 8 million voter turnout.)

A third of the polling stations—about 7,000—of country’s polling stations could be set aside for this deeper audit, but officials seem at odds over who should do it, and how to keep to the Aug. 1 timetable. According to Kate Clark at The Afghan Analysts Network:

If the ‘deep audit’ was to go ahead, Abdullah could theoretically be back in the race. 7000 polling stations, containing an unknown, but substantial number of votes, would create enough room for the result of the election to change radically. On the other hand, we could still be facing more protests by Abdullah from outside the electoral tent and no end, as yet, to the deadlock.

Abdullah won the first round in June with 44 percent of the vote—not quite enough to hit the 50 percent mark needed to avoid a run-off. Ghani trailed him with only 31.5 percent of the vote. Ghani could have mobilized and consolidated the Pashtun ethnic vote, which had been split between other candidates in the June election, (Ghani is a Pashtun, which represents some 42 percent of the Afghanistan population; Abdullah is half Pashtun and half Tajik, which counts for about 27 percent of people.) But to amass a lead of over a million votes—with a turnout that has surprised even the most seasoned election observers?

Some would say, as Jeffrey Stern, an American correspondent who has also done development work in Afghanistan, noted, that “the numbers are probably too good to be true.” Does that mean that Ghani is the mastermind of an elaborate fraud? “I do think there is something to it (fraud) but it would be very hard for me to believe that it is a top-down thing,” Stern told TAC. “I don’t think Ashraf Ghani himself orchestrated some plan to stuff ballot boxes. In some of those (polling stations) in the far east of the country, ballot stuffing was going to happen regardless of whoever the Pashtun was running.”

This is why the election officials, international observers, and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry are all insisting on three things: that the preliminary results aren’t final, that an audit must be conducted, and, most of all, that both sides calm down.

Some observers guess that Abdullah will step aside before letting things dissolve into an irrevocable schism. Both candidates’ supporters, however, have ramped up tensions on social media to the point that a ban on Twitter has been proposed to last until the end of the elections. After Monday’s announcements, both sides took to the streets, celebrating or protesting with gunfire, depending on their allegiances.

“I would say I’m worried but I’m not terrified,” said Stern. So far.

President Ghani?

Stern sat down with Ghani earlier this year in Kabul, and called him “one of the smartest people I have ever interviewed, period.” Like others, Stern said Ghani’s strengths are his intellect, sophisticated assessment of failed states, and seeming detachment from the tribal/factional machinery and ethnic politics that threatened to devour Karzai if he didn’t play ball over the last 13 years.

“What I would reserve judgment on is how good he is going to be with coalitions, and getting things done as a president and not just the head of one sector,” Stern said, referring to Ghani’s 2002-03 stint as finance minister under Karzai.

Nemat Sadat, a progressive activist who has been fighting for gay rights in Afghanistan, believes the ostensibly skewed results of the run-off were the result of heavy Pashtun turnout in favor of Ghani, not necessarily widespread fraud. Abdullah, Sadat said, is a “traditional powerbroker” who may generate protests and even chaos for a few weeks, but “has no political future in Afghanistan.”

“Many powerful figures from ‘the lost generation’ decades of civil war will be replaced by younger Afghans who are western-educated, technologically savvy and have a solid command of English,” he said in an email exchange, believing that Ghani is well positioned to usher in a new meritocracy that eschews the patronage and cronyism that built the poppy palaces and personal bank accounts for a small number of politically-connected Afghans in the post-Taliban years.

That hopeful vision aside, Sadat said the international community and Afghan masses “are not ready to endanger what little they have built for a fresh round of conflict that could spark an open civil war.”

There is little more the U.S. can do than to encourage an open and thorough audit, and advise against threats by Abdullah’s supporters to create a parallel government. Whether they can get it together will determine how involved Washington will be in the country moving forward. Most Americans may not even care. “At some point,” said Korb, “you’ve got to leave, and then it’s up to them.”

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos is a Washington, D.C.-based freelance reporter and TAC contributing editor. Follow her on Twitter.