Orthodoxy, LGBT, & Spiritual Sedition

You might not have seen this late update to the post from the other day about the Orthodox priest in Wichita, Father Aaron Warwick, who published an article on a pro-gay Orthodox website, Orthodoxy In Dialogue, in which he, among other things, called on the Orthodox Church to encourage gay people to commit themselves to partners, and keep their sexual activity within those partnerships.

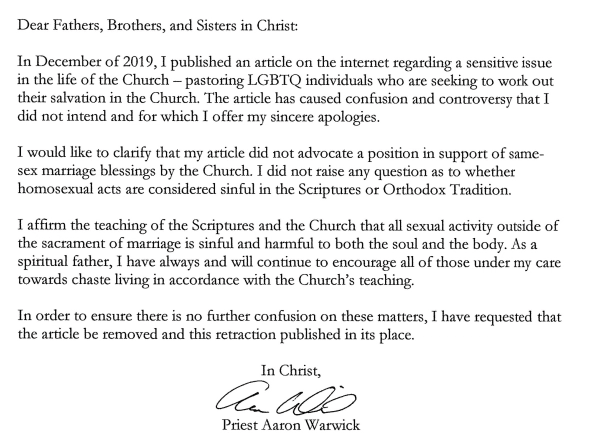

Here is the text of a public letter Father Warwick has now released — at the direction, I understand, of his bishop:

As of this writing, the original post is still there. Maybe the Orthodoxy In Dialogue editors refuse to remove it. I don’t know. But listen, whether or not the apology is sincere is not that important. What is important is the signal this sends from the Antiochian Orthodox hierarchy that the kind of thing Father Warwick did will not be tolerated, at all. It shouldn’t have taken almost two weeks for the bishop to act, but he did act, and that is a relief.

The Orthodox Church is small in America — maybe only one million adherents — so non-Orthodox may not be aware that Orthodoxy has become a refuge for a number of converts who saw their own churches fall to pieces over the inability to adhere to Christian orthodoxy on sexual matters, particularly on homosexuality.

Some background: Orthodox Christianity doesn’t have a central world headquarters, as Catholicism does, but it is rather more like a confederation of national churches, each with its own hierarchy, but united in belief. In the US, each Orthodox immigrant group brought its own churches, leading to a highly irregular situation here. All the Orthodox churches in the US have grown significantly by the influx of converts, both into the clergy and the laity (see here for more information on that); under their previous leader, the late Metropolitan Philip, the declining Antiochians threw the doors wide open to converts. Now, something like 90 percent of Antiochian clergy in the US are converts, and the church is thriving.

Now, as I was saying, the presence of so many converts, especially in the clergy, who came from churches going to pieces because of sexual issues (particularly homosexuality), means that there are more than a few people — clergy and laity both — who view with real alarm any signs of Orthodoxy going wobbly. A friend of mine and reader of this blog was received not long ago into Orthodoxy, along with his wife. They left the Episcopal Church, where he, at least, had spent his entire life. Their story is a familiar one: lies on top of lies from parish leadership about the church’s intention to hold the orthodox Christian line on sexuality — and then, after all the “dialogue” and appeals to “tolerance,” when the pro-gay liberals got the upper hand, they showed faithful traditionalists the door.

If you spend any time asking Orthodox converts who are 40 and over to tell their stories, you’ll hear lots of accounts like that. When I posted the piece the other day about Father Warwick’s essay, the friend I mentioned in the previous paragraph hit the roof. He was ready to knock heads over it — and he was right to be! He has already lost one church home to sexual progressivism; he is not willing to lose another.

His story is not exactly mine, but they run on parallel tracks. As regular readers know, I went to Orthodoxy after losing my ability to believe in the truth claims of the Catholic Church, after years of reporting on the abuse scandal. I have no interest in arguing theology or ecclesiology here, so don’t bother starting an argument about that in the comments; I’ll just delete your remarks. For me, a return to Protestantism wasn’t possible, for reasons of theology and ecclesiological conviction. That left Orthodoxy as my only possibility. Complicated story, not worth telling here.

It turns out to have been my real home all along, and I’m grateful for the gifts God has given me in Orthodoxy. One of the best ones, for a Christian like me who had been heavily engaged in front-line fighting within the Catholic Church over moral and theological issues, was the sweet relief of knowing that these fights weren’t happening within the Orthodox Church. Of course there was and is progressive dissent, but it doesn’t have nearly the platform or the standing that it does in Catholicism. Nor do progressives have the mechanism to change the teaching and practice of the Church as it does in Catholicism. It was such a blessing to be able to go to liturgy on Sunday morning and not feel that you were entering some sort of battlefield.

I never, ever believed that any church was a safe place from scandal or from theological conflict. This is true of the Orthodox Church, like any other church. But to be candid, there is a lot to be said about the lack of gay clergy, compared to Catholicism. I’m not sure why it is; perhaps the married priesthood has something to do with it. But it’s real. And maybe because the Orthodox priesthood is not so gay-friendly, that may explain in part why the institutional church itself hasn’t cracked under pressure to engage in “dialogue,” to practice “inclusiveness” and “welcome,” and all the other strategies that are always and everywhere the first step to overturning orthodox theology and practice. It is certainly the case that the strong presence of converts who fled churches whose moral theology had been corrupted by contemporary sexual ideology stiffens the institutional spine.

There are a number of Orthodox jurisdictions in the US — Greek, Russian, OCA, Antiochian, etc. — and some of them struggle with this stuff more than others do. But if you come to Orthodoxy from a Mainline Protestant, progressive Evangelical, or Roman Catholic background, you will be amazed and gratified by how different the atmosphere here is on that front. I’ve heard over the past day or two that a lot of Orthodox clergy, across jurisdictions, had seen the Warwick essay, and felt strongly that this kind of thing has to be nipped in the bud at once. Too many such priests have the hard, punishing experience of seeing where it leads.

In his apology letter, Father Warwick claims that he never advocated changing church teaching. This is a distinction without a difference. He was following the successful misdirection that Father James Martin, the pro-LGBT Jesuit, uses to normalize sexual heterodoxy: claiming to only be about changing pastoral practice, not altering official teaching. This allows these change agents to pretend to be orthodox, while changing facts on the ground. That effort has come to a crashing stop in the Antiochian church now, and for that let us rejoice. But let us continue to be vigilant. I came out of a church whose moral authority is badly compromised because it does not know how to deal with homosexuality among the bishops, the lower clergy, or anywhere else. If Orthodoxy opens its doors to this, God help it.

I’ll leave you with a couple of passages from an article that the Orthodox Biblical scholar Bradley Nassif wrote about homosexuality. It appeared in the pro-LGBT Orthodox journal The Wheel, which has no links for non-subscribers. Dr. Nassif sent me a copy of his essay, which, contrary to the general editorial line of the magazine, defends Orthodox teaching on homosexuality. These two passages can’t possibly do justice to why Orthodoxy believes the things it does about homosexuality, but it will give you a sense. In the first one, it’s a matter of the plain teaching of Scripture, which has authority over us:

In recent years, considerable effort has been exerted to re-interpret the plain meaning of these texts through an alternate “gay reading” of Scripture. Much of it, however, has been rejected as eisegesis [reading meaning into text — RD] by biblical scholars, even by those who promote a gay agenda such as the well-known Roman Catholic scholar Luke Timothy Johnson, who frankly admits:

I have little patience with efforts to make Scripture say something other than what it says through appeals to linguistic or cultural subtleties. The exegetical situation is straightforward: we know what the text says. . . . [However] we must state our grounds for standing in tension with the clear commands of Scripture. . . and appeal instead to another authority when we declare that same sex unions can be holy and good. And what exactly is that authority? We appeal explicitly to the weight of our own experience and the experience thousands of others have witnessed to, which tells us that to claim our own sexual orientation is in fact to accept the way in which God has created us.

Johnson’s rejection of biblical authority in exchange for the authority of his own personal “experience” and those of others is a bold and honest admission. While Orthodoxy values the testimony of human experience as one of several signs of God’s will, it can never agree with Johnson that it should be the main source for determining Christian doctrine. Otherwise there would be as many truths as there are experiences. Johnson is correct in concluding that the Bible is clear in its teaching about homosexual practice, even though he disagrees with it. The Church’s consensual tradition on this topic is likewise unambiguous: all homosexual acts are sinful because they have no procreative value (Gen. 1:28), they are a repression of the visible evidence in nature regarding male-female anatomical and procreative complementarity (Rom. 1:26–27), they violate the “image of God” in those who commit them and in others (Gen. 1:27), and they are a parody of the “one flesh” union (Gen. 2:24, Matt. 19:5, Eph. 5:21). This is not to say that homosexual “orientation” is an act of sin even though it is a symptom of human corruption no worse than other passions of the flesh that afflict all humans (Gal. 5:19–21).

In this passage, Dr. Nassif explains that it also has to do with Christian anthropology. What is man? What is the relationship between soul and body?

The starting point for a Christian understanding of sexuality and the nature of the human person is the same starting point as many other questions in Orthodox theology, namely, the incarnation of the Word

(John 1:14). The incarnation is the fundamental dogma of all theology. A theology of sex begins with the apostolic encounter with the human Jesus and the revelation of his saving identity for humanity as a

whole. The revelation of the glorified, paschal humanity of the Lord, and not the “old Adam” of Gen. 1–2, makes the person of Christ, the “new Adam,” the primary focus of the Church’s affirmations about human nature because Jesus is the fulfillment of God’s creational purposes.The old Adam of Gen. 1–2 was “a type [typos] of him [Christ] who was to come” (Rom. 5:14). Adam was a lesser shadow of the greater antitype fulfilled in the human Son of God. The incarnation, therefore, provides the basic components for understanding what it means to be human. Those components include the following affirmations: (a) created humanity (physicality) is good; (b) human nature is fundamentally a commingling of material and immaterial, both being sacred; (c) gender identity continues in the resurrection; the physical, male characteristics of the paschal humanity of Christ remained recognizable to his disciples. Sexual identity is an essential part of Jesus’ personality, and personality is retained in the resurrection; (d) human beings are theocentric creatures. We cannot be fully human

apart from union with God. Perfect union with God is revealed and healed through the harmonious activity of the divine and human natures, wills, and saving work of the incarnate Logos (contra Eutychian, Nestorian, Monothelite, and aphthartodocetic constructions). Hence, christological anthropology is teleological. The incarnation is the ultimate expression of what it means to be human, now and in the age to come.

More:

The human being, therefore, is at once an ensouled body, and a bodily soul. One’s personal identity and wholeness is bound up with this interconnection. The body is the visible, objective expression of the life of the soul. What happens to the body happens also to the soul, and what happens to the soul happens also to the body. The totality of human experience—including not only sexual experience but also eating, drinking, joy, sadness, sickness, health, and death—is not merely a matter of physicality. Rather, these experiences are those of a human subject and therefore the human soul of a person. The implications for human sexuality direct us during this present life to strive for wholeness and health for ourselves and others. If one is to take responsibility for one’s sexual life as a human being, it will be exercised in such a way that it upholds the full humanity of the other.

A same-sex marriage cannot be a holy thing in Orthodox teaching; nor can marriage be understood as anything less than an icon of the relationship between Christ and the Church:

A holy sexual bond requires two, and only two, different sexual halves (“a man” and “his wife”), brought together into one sexual whole (“one flesh”).11 This complementarity is a reflection of God himself, since male and female together are made in God’s image.

Gender differentiation and sexuality are essential components of human nature. Masculinity and femininity

are adjectival, an aspect of our humanity. Thus, there are only two ways to be fully human: either as male or as female. Any other form is a symptom of the corruption of human nature that has come as a result of the fall. These forms include adultery (Exod. 20:14; Matt. 19:18), fornication (1 Cor. 6:15–18), homosexuality (Lev. 18:22; Rom. 1:26–27), incest (Lev. 20:11–21), bestiality (Lev. 18:23; 20:15–16), and lust (Matt. 5:28).12 Positively speaking, in briefest terms, the sacrament of Christian marriage is to be heterosexual, monogamous, non-incestuous, socially visible, socially affirmed, physical, permanent,

sanctifying, and eschatological.Accordingly, Orthodox Christianity views the “one flesh” union as a profound mystery that images the love between Christ and the Church (Eph. 5:31–32). Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians uses the marital analogy as a public picture of the intimate union between Christ and the Church. Saint John Chrysostom observes how this union takes on an ecclesial character that makes the Christian home “a little church.” Heterosexual, monogamous marriage functions as a redemptive analogy of the exclusive relationship between Christ and his bride, the Church. The female imagery of the Church’s bridal relation to Christ, the male bridegroom, is used in Ephesians 5 to manifest the mystery of salvation when Paul quotes the Genesis text, “‘the two shall become one flesh.’” “This mystery is a profound one,” says Paul, “and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church” (Eph. 5:29–32). There is thus a soteriological, iconic dimension to marriage and human sexuality that are to be understood in light of God’s self-revelation in Christ (the male bridegroom) and the Church (his female bride).

Along these lines, the Orthodox wedding icon (see above), which depicts the Wedding in Cana, is not an arbitrary image, but gives us a theophany, a divine revelation, of the relationship of Christ to His Church through a wedding. Orthodox priest Michael Gillis explains the meaning of the icon, in which Jesus Christ is present, but not at the center.

Granted, Father Warwick was not proposing that the Orthodox Church begin to offer marriage to same-sex couples, though he was in fact suggesting that the church bless them living in pseudo-marriage. I bring up the Wedding in Cana only to point out how entwined Orthodoxy’s teaching on marriage is with its teaching on sexuality. You cannot disentangle them. The Orthodox belief is not arbitrary, or shallow. You may consider it to be wrong, but you cannot say that it is trivial, or based on prejudice. For the Orthodox, to lose sight of these profound, God-given truths about human nature, marriage, and God would constitute a dramatic falling-away from God. I say “for the Orthodox,” but it’s true for all Christians. Many churches have lost this vision of the Good. Others, like the Catholic Church, are engaged in an all-out internal struggle over it. There can be no question that the Orthodox Church needs to do a much better job explaining its teaching to its people, and helping gay and lesbian brothers and sisters walk that particularly hard road they have been given on our shared pilgrimage. (This is not an abstract issue for me; I have a gay Orthodox friend who is chaste, and with whom I talk about his struggles.)

Last year, I published a long, heartfelt letter from an Orthodox Christian living in an Orthodox country, talking about how vicious the public rhetoric, especially from churchmen, is towards gays. The cruelty he describes is not Christian! The Church has to figure out how to hold the line for the Truth while also treating gays and lesbians with dignity and compassion, not with anger and contempt. That said, the idea that to fight this cruelty we must surrender the truth of God’s revelation to us about who He is, who we are, and how we are to live out our holiness with Him in our bodies — that must be firmly rejected. It is a false choice to say that we must choose between viciousness towards gays, or our moral theology.

We can see from the experiences of the Mainline Protestant and Catholic churches how hard it is to defend when you give the heterodox standing — especially given that the heterodox have behind them an entire culture and its propaganda machine. Just today, the United Methodist Church announced plans for a formal schism between those faithful to Biblical teaching, and heterodox progressives. We in the Orthodox Church have to hold the line, no matter what the world throws at us. Whether he knows it or not, Father Warwick’s seditious, Jim Martin-style sentimentality will lead to the dissolution of the Orthodox faith’s teaching on sexuality and marriage. It is certainly true that this teaching is wildly unpopular these days. That is not a judgment upon the Orthodox Church, but upon the world that will not have a God that tells it thou shalt not. For those who wish to be faithful and obedient, the bishops, priests, and theologians of the Orthodox Church must stand firm in the truth. There are countless numbers of us — I am one — for whom the Orthodox Church is the last, best hope in this post-Christian desert, and who have received its teachings, even its hard ones, as liberation. Glory to God for it!

So look, bishops and priests: do not lead us back to that Egypt from which we came!