Modern Art: When a Banana is Just a Banana

I’ve always been something of an art afficionado. I suppose it runs in my blood: my cousin, William R. Davis, is a well-known painter from Cape Cod. He’s a traditionalist (another family trait, it seems), known for his romantic seascapes. His portraits of tall ships cutting through unforgiving Atlantic tides fetch a fair price at market. A print of his best-known work—Steamboat Mt. Washington on Lake Winnipesaukee, NH—hangs over our mantle. If you look very closely at the passengers on deck, a rather dashing chap is yacking over the portside railing.

In an art studio somewhere in the Australian Outback, there’s a painting I own by a Renaissance woman named Lin Van Hek. Lin is best known for her music—particularly her song “Intimacy,” which appeared in the soundtrack for the original Terminator film. I bought it after befriending her partner, Joe Dolce—himself best known for his hit single Shaddap You Face. I first got to know Joe as an extraordinarily talented poet and essayist when I worked for the Australian literary magazine Quadrant.

I’ve even dabbled in art criticism. Last year, a letter I wrote to the editor of The Spectator was published in those hallowed pages. To wit:

Sir: I must emphatically disagree with Lionel Shriver when she says, ‘A purity test for artists is the end of art’ (16 December). Censor is the greatest muse. Caravaggio is never so brilliant as when he’s trying to camouflage his homoeroticism, or Shakespeare his Roman Catholicism. Great art is so often transgressive, but it must have something to transgress. Ms Shriver should instead lament the dreadful quality of our censors—the progressive left—and pray for a better class of villain than Louis C.K.

“Rules are meant to be broken,” as we say—and that’s precisely why rules themselves have become avant-garde. In a lawless age, the lawman is the ultimate outlaw. No one is more transgressive than the conservative.

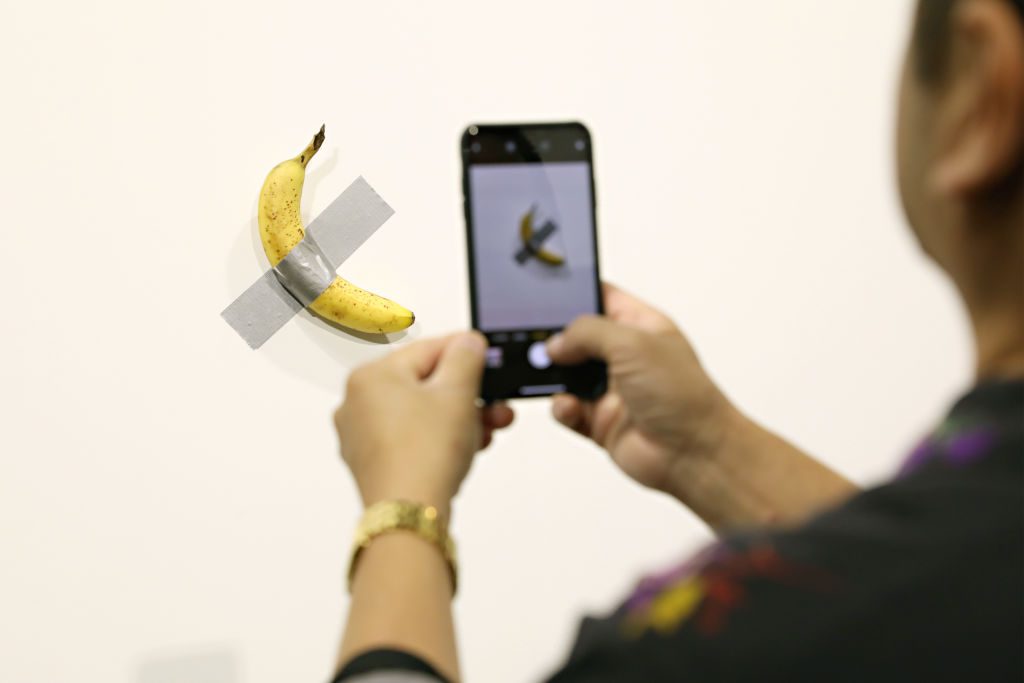

Yet the revolutionary has yet to become as bold as the reactionary. Exhibit A: last week, the artist Maurizio Cattelan fetched a cool $150,000 for his latest masterpiece, a banana he taped to the wall of an exhibit in Miami Beach.

According to an interview with Artnet, Mr. Cattelan originally cast the banana in bronze and resin. But something was missing. “Wherever I was traveling I had this banana on the wall,” he explained. “I couldn’t figure out how to finish it.” Then it hit him: “One day I woke up and I said ‘the banana is supposed to be a banana.’”

The less cultured among us can only imagine the epiphanic moment—the dream within a dream—during which Mr. Cattelan realized that bananas are bananas. Nevertheless, I urge you to try, if only to better appreciate the creative process. After four years of art school, Mr. Cattelan must have cycled through countless theories of what a banana is “supposed” to be. Is it a kind of phallic idol? A slippery, cylindrical manifestation of the Golden Fleece? A commentary on the U.S.-backed 1954 coup in Guatemala on behalf of the United Fruit Company (now known as Chiquita)?

Imagine him awaking with a jolt, drenched in a cold sweat, with some sweet muse whispering in his ear: “The banana is supposed to be a banana.” He arises from his bed, naked from the waist down. In a kind of mystical trance, Mr. Cattelan walks into his kitchen. One hand shoots out from his side and pulls back a drawer; with reverent awe, he removes a roll of duct tape. He raises the roll to his mouth and, in an erotic frenzy, tears off a strip. One trembling hand reaches into the fruit bowl. Slowly—slowly—he removes a banana. He feels its supple form, its fibrous weight; he raises it to the wall and…

Well, some things are too sacred to be spoken aloud.

♦♦♦

Many conservatives will pooh-pooh Mr. Cattelan’s revelation. But that is the height of impiety. Modern man is asked to grapple with no more difficult truth than this: “The banana is supposed to be a banana.” From Aquinas to Aristotle, the greatest philosophers in the history of Western civilization have stood in awe at the thingness of things.

“I will show you fear in a handful of dust,” said Eliot. Maurizio Cattelan has done him one better: “I will show you banana-ness in a handful of banana.”

Yet already the mind of the curious modern begins to yearn for the next great adventure. His soul craves even greater blasphemies. “You say a banana is a banana,” his thinking goes, “and I agree. But what’s a banana for…?”

Here we come to the moment of apotheosis. The great artist, like Mr. Cattelan, may be content to see bananas hanging on walls like Botticellis. He may string them from the rafters like Rubenses. He may imagine the walls of Troy decked from top to bottom with rotting Musaceae—offered, unburnt, to fickle Athena to retain her favor. But the subaltern whispers a single heresy in hushed tones: “Bananas are for eating.”

Enter the artist David Datuna. On Saturday, Mr. Datuna strode up to Mr. Cattelan’s exhibit in Miama, pulled it off the wall, and began to munch happily on the artwork. “Art performance,” he announced to onlookers. “Hungry Artist.”

Mr. Datuna was shortly hauled off to the gallery’s brig. “See you after jail,” he called to his adoring masses. We can only hope. Godspeed, dear sir.

Great artists are never appreciated in their lifetime, and this will undoubtedly be the case with Mr. Datuna. We have only begun to understand that “the banana is supposed to be a banana,” as a great man once said. But it may be several generations yet until we realize that bananas, in their banana-ness, are for eating. Then, and only then, the walls of Troy will fall, and Wisdom herself will be sated on the spent peels of that sweet produce.

Things will fall together; extremes will not hold; mere order will be loosed upon the world. Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ will be emptied into Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, and its Corpus hung in the spot that Mr. Cattelan’s fruit kept warm. And we will all eat the fruit of Mr. Datuna’s genius—a cabal of Gnostics made privy to the secret wisdom that the banana is, indeed, supposed to be a banana.

Michael Warren Davis is the editor of Crisis Magazine. Read more at www.michaelwarrendavis.com.