Every Day Is Like Sunday: Rediscovering Wilfrid Sheed’s “The Hack”

Don’t call Wilfrid Sheed’s 1963 The Hack a forgotten Catholic classic. I don’t want it to be dismissed so easily.

Sheed was the scion of Frank Sheed and Maisie Ward, the Catholic publishers and apologists; he knew that pre-Vatican II world of professional religion from the inside. The Hack is a satirical tragedy about Bert Flax, a man who supports his wife and five children by writing pabulum for the lower levels of the Catholic press: angels with cotton-candy wings, Irish-surnamed Fathers playing improving outdoor games with hearty children, sub-Chestertonian cutesy polemics. Over the course of a particularly harrowing Advent (in a nice touch, it isn’t ever called Advent but always Christmas) Bert slowly realizes that his work–and perhaps his faith–have always been childish, sickly-sweet, and unreal.

The Hack comes from a specific immediately pre-Vatican II subculture, but its emotional and spiritual concerns feel totally at home in our mommy-blogging, #soblessed performance culture. This is a book about meta-emotions: what we feel about what we feel. It’s a book about knowing yourself utterly inadequate to the mystery of God, but not knowing how to express that without tinsel and puff; and about the duty we feel to manufacture and display the correct emotions. You have to stay strong for the children! You’re an inspiration.… You should be grateful, you should be present in the moment, you need to really feel it.

Both Bert and his wife Betty are haunting creations. The book is full of incisive phrases, painful pastiche, and the occasional jack-in-the-box moment of perfect comic timing. (I laughed out loud when Betty realizes, in a seemingly irrelevant discussion, that her mother used to snoop around in her diary.) As Bert and Betty separately lose their shaky grips on reality–or, more accurately, realize that they let go a long time ago, like Wile E. Coyote finally looking down into the canyon–the novel skids into patches of stream-of-consciousness fever dream.

The novel has a couple of minor flaws. Certain points are spelled out a bit too clearly toward the end, and the last third of the book has quite a bit of repetition. It bangs on a bit, is what I’m saying. But the book’s weird style is a big part of its impact: One moment it’s darting in with a shiv, the next it’s galumphing around with a shovel. It’s an unsettling book.

Bert’s faith is as noticeable for what it leaves out as for what it contains. He’s like the wooden tchotchke my grandparents had, which looked like an abstract angular artwork until you realized that the empty space spelled JESUS. You get a little bit of “the Christ child” but that’s about it. The portrayal of backslapping, flop-sweat, forced religious faith is terrific: “Anyway, apart from anything else, it wasn’t true that he didn’t believe; belief was an act of the will, and he was willing like crazy right now.” And Bert’s version of the publican’s prayer is genuinely moving, in the Sunday-obligation Mass scene which opens the book:

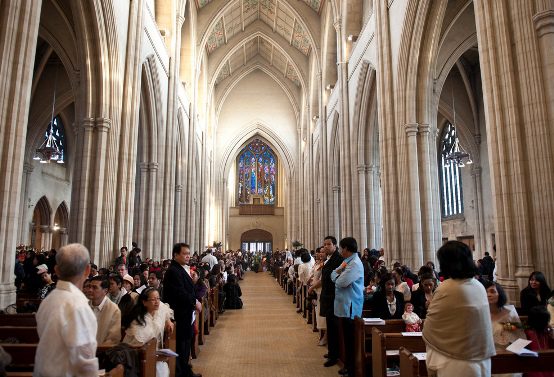

The first drippings were beginning to come loose down the aisle. Mothers who had to get back to their children, and mothers who had to get their children out of there: in a moment, the rout would be on. He whispered a frantic piece of prayer, “Sorry to mess it up again,” and slid out ahead of them. Another Sunday shot to hell.

But there’s a lot in The Hack for non-Christians as well. It’s about how we accept shoddy work and emotional dishonesty, both from ourselves and from others: because we think it’s good-enough, or it’s all that we’re capable of, or it’s what other people really want. Bert is forced to perform his trinkety faith in order to feed his family, but then, all of us end up faking the best parts of ourselves sometimes, in order to set a good example or maintain familial harmony or because we don’t know what else to do. And none of us are adequate to our ideals; even our ideals aren’t adequate to the love, hope, truth, or justice of which the ideals are merely chintzy mental effigies.

The Hack is a painful read–convicting, as our Protestant friends say. There’s a lot of empathy behind its jabs. Here’s Bert remembering the state of relief and self-emptying in which he wrote his first poem, after an exhausting August stickball game in his boyhood:

Fatigue had dripped away, from his hands and his feet. That’s right, his feet hadn’t hurt at all as he ran home. He remembered perfectly: the feeling had been absolutely good.

If only he hadn’t dragged it around for so long, like a dead cat….

That’s deflating, sure; but it’s also something I think most of us can relate to. The Hack is about realizing how stale and joyless one’s love has become–and, worse than that, how cheesy it was even when it was good.