Dante: Seeing, Loving, Believing

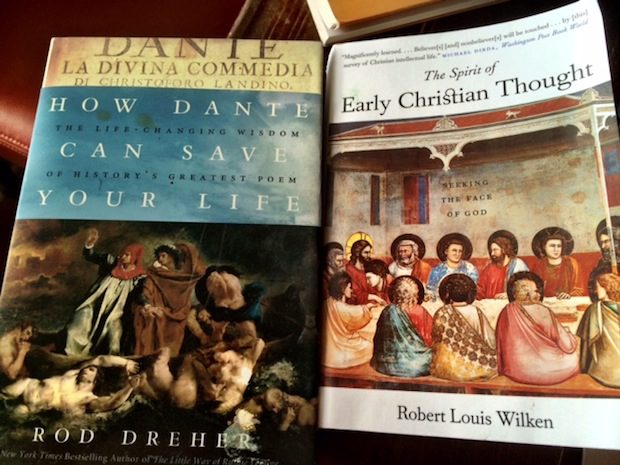

I’ve just heard from my publisher that the hard copies of How Dante Can Save Your Life have just arrived. And I’ve been making plans this morning to visit various colleges and universities to talk to students about Dante. One of the country’s top Dantists e-mailed yesterday to thank me for sending him the galleys, and to say he has just begun reading it:

It is exactly the right way to think about Dante, and to approach what he is really doing. I can’t wait to plunge in fully — in fact, it’s very hard to wrench oneself away from it! Just your introduction puts in lucid, succinct terms what I try to get across to my students.

Here is a passage from the introduction:

Dante’s tale is a fantasy about a lost man who finds his way back to life after walking through the pits of hell, climbing up the mountain of purgatory, and ascending to the heights of heaven. But it’s really a story about real life and the incredible journey of our lives, yours and mine.

The Commedia is a seven-hundred-year-old poem honored as a pinnacle of Western civilization. But it’s also a practical guide to life, one that promises rescue, restoration, and freedom. This book, How Dante Can Save Your Life, tells the story of how the treasures of wisdom buried in the Commedia’s 14,233 lines gave me a rich new life.

Though the Commedia was written by a faithful Catholic, its message is universal. You don’t have to be a Catholic, or any sort of believer, to love it and to be changed by it. And though mine is a book that’s ultimately about learning to live with God, it is not a book of religious apologetics; it is a book about finding our own true path. Like the Commedia it celebrates, this book is for believers who struggle to hold on to their faith when religious institutions have lost credibility. It’s a book for people who have lost faith in love, in other people, in the family, in politics, in their careers, and in the possibility of worldly success. Dante has been there too. He gets it.

This is a book about sin, but not sin in the clichéd, pop-culture sense of rule breaking and naughtiness. In Dante, sin is the kind of thing that keeps us from flourishing and living up to our fullest potential, and it’s also the kind of thing that savages marriages, turns neighbor against neighbor, destroys families, and ruins lives. And sin is not, at heart, a violation of a legalistic code, but rather a distortion of love. In Dante, sinners—and we are all sinners—are those who love the wrong things, or who love the right things in the wrong way. I had never thought about sin like that. This concept unlocked the door to a prison in which I had been living all my life. The cell opened from the inside, but I had not been able to see it.

This is also, in many ways, a book about exile. What does it mean to know you can never go home? This was Dante’s dilemma—and in a different sense, it was mine. Three years ago, when I returned after nearly three decades to live in my Louisiana hometown, I thought I had ended a restless journey that had taken me all over America, searching for a place where I could be settled and content. To my shock and heartbreak, I was wrong. The most difficult journey lay ahead of me: the journey within myself. Dante showed me the way through. He can do the same for you.

Further, I say:

For the poem to work its magic on the reader, it has to be taken up into the moral imagination in a personal way. You have to engage in dialogue with our Florentine guide along the pilgrim’s path. When I gave myself over to him, I found that Dante is not a remote figure from an alien world but a warm companion with whom I had far more in common than I could have imagined. He is simply a fellow wayfarer who has seen great things, both terrifying and glorious, along life’s way, and wants to tell you all about it.

That last passage came to mind just yesterday, with my reading of the thrilling work by historian Robert Louis Wilken, The Spirit of Early Christian Thought. In these passages, Wilken writes of Augustine’s answer to the Manichees, who said that they would believe nothing that couldn’t be demonstrably proven. Augustine says that religious knowledge doesn’t work like that — and in fact, an enormous part of everyday life depends on believing things on authority. Says Augustine, “Nothing would remain stable in human society if we determined to believe only what can be held with absolute certainty.”

(For a glimpse at a society in which nothing that has not been witnessed or experienced oneself, or by a living person known to one, can be considered true, check this out.)

As Wilken writes, Augustine said without trust and authority, learning becomes impossible. To learn a foreign language, for example, requires trusting that the teacher knows how to speak it. Learning how to play the violin requires an apprenticeship to one who knows how to play the violin. You cannot think yourself into being a violinist or a speaker of French.

So it is with religious knowledge, Augustine argues. Writes Wilken:

By bringing up these kinds of examples, Augustine wishes to say that the knowledge acquired by faith is not primarily a matter of gaining information. The acquiring of religious knowledge is akin to learning a skill. It involves practices, attitudes, and dispositions and has to do with ordering one’s loves. This kind of knowledge, the knowledge one lives by, is gained gradually over time. Just as one does not learn to play the piano in a day, so one does not learn to love God in an exuberant moment of delight. If joy does not find words, if it does not exercise the affections and stir the will, if it is not confirmed by actions, it will be as fleeting as the last light out of the black west. The knowledge of God sinks into the mind and heart slowly and hence requires apprenticeship. That is why, says Augustine, we must become “servants of wise men.”

Wilken says that the only way to learn from an author is to surrender oneself to him, and to a teacher that knows and loves the work. The Manichees, he says, believed the thing to do was to begin attacking the work before one has loved it or understood it.

But, says Augustine, the only way to understand Virgil is “to love him.” Without sympathy and enthusiasm, without giving of ourselves, without a debt of love, there can be no knowledge of things that matter. Even though at the outset we may be unable to explain what is to be gained from reading Virgil, we expect to profit from reading him, says Augustine, because “our elders have praised him.”

The first question then becomes not “What do I believe?” but “Whom should I believe?,” or “Which persons should I trust?” Therefore, writes Wilken, if you would seek truth in religion, first seek to know and to love those whose lives are formed by the religious teachings. “Augustine is not speaking about blind obedience or leaping into the dark or submitting to someone else’s dictates,” says Wilken. “He is speaking about placing one’s confidence in men and women whose examples invite us to love what they love.”

This is exactly what the pilgrim Dante has to do when the shade of Virgil comes to him in the dark wood. He cannot prove that Virgil is real, and he cannot ask Virgil to lay out for him in advance the full itinerary of their voyage through the underworld. All he can do is say, in effect, “I trust you; I will follow.” That’s what happened to me when Dante came to me in the middle of my own dark wood. I did not know enough about him or the Commedia to give myself over to Dante in full knowledge of what I was doing. It seemed right, but what could I tell after reading only a couple of cantos? I trusted in the poet’s authority, and I did so because so many men and women over the centuries have extolled Dante.

I hope my book gives a credible account of what I saw when I went walking with Dante, and the marvelous things that pilgrimage did for me. I wrote it not as a scholar, but as a witness. And this is something else I’ve learned about the early church from reading Wilken: how much of its authority depends on witness, on things seen. Here is Wilken again:

Nothing in the mind can ever have the solidity of what is seen and touched. By constant immersion in the res liturgicae [liturgical thing] early Christian thinkers came face to face with the living Christ and could say with Thomas the apostle, “My Lord and God.” Here was a truth so tangible, so enduring, so compelling that it trumped every religious idea. Understanding was achieved not by stepping back and viewing things from a distance but by entering into the revealed object itself.

And:

What Augustine is seeking is not a theological concept or an explanation as such, but the living God who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the “Trinity that is God, the true and supreme and only God.” If one asks, What does it mean to find the one God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit? the answer is not so obvious. Finding means more than simply getting things straight or discovering the most appropriate analogy in human experience for the Triune God. There can be no finding without a change in the seeker. Our minds, he says, must be purified, and we must be made fit and capable of receiving what is sought. We can cleave to God and see the Holy Trinity only when we burn with love.

This is what the Commedia is all about: a progression in seeing, one that can only be made as one progresses in loving. You cannot hope to see God until and unless you order your loves rightly. It is a journey — not one that follows a straight line (it’s no coincidence that the paths into Hell and up to the Earthly Paradise are spiral) — but a journey whose progress depends on the capacity for one to see the world as it truly is. The more purely your heart loves, the more deeply your eyes see.

In Dante, seeing is believing, but believing is also seeing. The problem comes when our loves are disordered, and our hearts direct our eyes to see selectively. From How Dante Can Save Your Life:

For Dante, the power of images is supremely important. Dante shows us like nobody else that good and evil are not abstractions but take particular forms. An image is never just an image; it always points to something else.

In the realm of Dante’s afterlife, images are reality. The pilgrim’s movement toward unity with God is measured by his increasing ability to see things as they really are. Believing is seeing. Not so in the mortal life, when images can serve as a veil hiding the true nature of the evil men do.

The French have a saying: “To understand all is to forgive all.” In one sense it’s an exhortation to empathy: if we truly put ourselves in the shoes of a wrongdoer, we may find it easy to forgive. In another sense it is a warning against too much empathy: our identification with a wrongdoer may blind us to the seriousness of that person’s sin.

Consider one notorious example: In 1996, Boston’s Cardinal Bernard Law penned a letter to Father John Geoghan, granting him early retirement. “Yours has been an effective life of ministry, sadly impaired by illness,” the cardinal wrote. You would never know from the gentle, fatherly tone of the letter that Father Geoghan had spent his priestly career raping and sodomizing children in multiple parishes in the archdiocese, and that Cardinal Law and his predecessors had full knowledge of his actions. They had simply moved the pedophile from parish to parish. This kind of thing happened over and over: bishops seeing sexually abusive priests with sympathy, and regarding victims and their families as abstractions at best and at worst as enemies of the Church.

Do I believe that these bishops wanted to see children abused? No. I think they were so corrupted by the image of the priesthood and the Church as something wholly noble, pure, and good that their will to act was paralyzed in the face of information challenging the truth of that image.

And, as I write about later in the book, it was only through reading Dante, and the revelations about my own heart that Dante showed me, that I came to understand how I had judged the Catholic Church unfairly over the scandal, and what my own disordered loves had to do with it.

I’m telling you, surrendering to Dante is not for the timid. He will take you to places within yourself that are hard to traverse. But he will also take you to places that surprise you, delight you, and raise you up higher than you imagined you could go.

But first, you have to trust him as a witness. If I have done my job as a witness, you will be prepared to give yourself to Dante. My book is not an argument for why you should read Dante. It is a story. It is a kind of testimony. The things I talk about in that book really happened. Writing this book was an act of love, and a gesture of gratitude to the great man of Tuscany whose suffering gave birth to a work of literature through which the light of divinity shone down the centuries and into my heart like a searchlight and a lighthouse. One more passage from How Dante (pre-order it now so you’ll be among the first to get it) about the pilgrimage of thanksgiving I made last fall to Dante’s grave in Ravenna:

I prostrated myself on the floor, then after a moment rose and stepped forward to kiss the tomb. Then for a moment I simply stood still in the presence of the great man whose masterpiece had saved my life.

I thanked him for what he had done for me. And I thanked God for the life and trials of Dante Alighieri, who turned his own suffering to great good and reached across the centuries to rescue me, as he, in his imagination, had been rescued by Virgil and Beatrice.

I asked for his prayers that I would write well of him, and in so doing reflect for the eyes of others the saving love God showed to him and which he passed on to me.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.