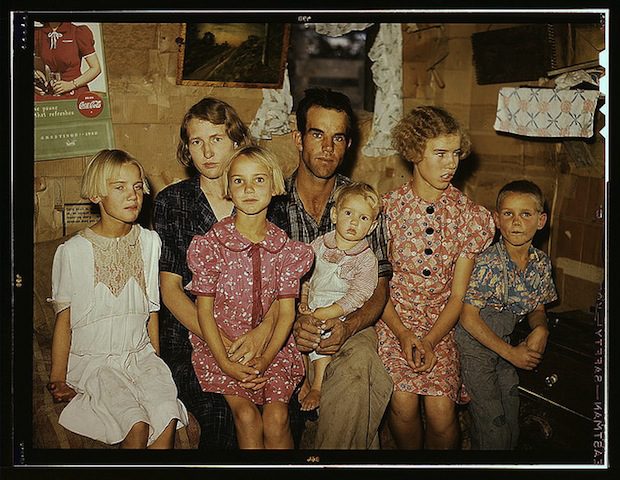

Why Poor People Act That Way

I smoke. It’s expensive. It’s also the best option. You see, I am always, always exhausted. It’s a stimulant. When I am too tired to walk one more step, I can smoke and go for another hour. When I am enraged and beaten down and incapable of accomplishing one more thing, I can smoke and I feel a little better, just for a minute. It is the only relaxation I am allowed. It is not a good decision, but it is the only one that I have access to. It is the only thing I have found that keeps me from collapsing or exploding.

I make a lot of poor financial decisions. None of them matter, in the long term. I will never not be poor, so what does it matter if I don’t pay a thing and a half this week instead of just one thing? It’s not like the sacrifice will result in improved circumstances; the thing holding me back isn’t that I blow five bucks at Wendy’s. It’s that now that I have proven that I am a Poor Person that is all that I am or ever will be. It is not worth it to me to live a bleak life devoid of small pleasures so that one day I can make a single large purchase. I will never have large pleasures to hold on to.

There’s a certain pull to live what bits of life you can while there’s money in your pocket, because no matter how responsible you are you will be broke in three days anyway. When you never have enough money it ceases to have meaning. I imagine having a lot of it is the same thing.

Poverty is bleak and cuts off your long-term brain. It’s why you see people with four different babydaddies instead of one. You grab a bit of connection wherever you can to survive. You have no idea how strong the pull to feel worthwhile is. It’s more basic than food. You go to these people who make you feel lovely for an hour that one time, and that’s all you get. You’re probably not compatible with them for anything long term, but right this minute they can make you feel powerful and valuable. It does not matter what will happen in a month. Whatever happens in a month is probably going to be just about as indifferent as whatever happened today or last week. None of it matters. We don’t plan long term because if we do we’ll just get our hearts broken. It’s best not to hope. You just take what you can get as you spot it.

I am not asking for sympathy. I am just trying to explain, on a human level, how it is that people make what look from the outside like awful decisions. This is what our lives are like, and here are our defense mechanisms, and here is why we think differently. It’s certainly self-defeating, but it’s safer. That’s all. I hope it helps make sense of it.

We have talked about these things many times on this blog. All I want to say in this instance is that a society that doesn’t offer realistic hope to people like Linda Tirado that they can escape poverty through hard work and self-discipline is an unjust society, and needs to be reformed.

Relatedly, Vicki Madden explores why college kids from poor or working-class backgrounds struggle so hard to succeed. Excerpts:

In spite of our collective belief that education is the engine for climbing the socioeconomic ladder — the heart of the “American dream” myth — colleges now are more divided by wealth than ever. When lower-income students start college, they often struggle to finish for many reasons, but social isolation and alienation can be big factors. In “Rewarding Strivers: Helping Low-Income Students Succeed in College,” Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl analyzed federal data collected by Michael Bastedo and Ozan Jaquette of the University of Michigan School of Education; they found that at the 193 most selective colleges, only 14 percent of students were from the bottom 50 percent of Americans in terms of socioeconomic status. Just 5 percent of students were from the lowest quartile.

I know something about the lives behind the numbers, which are largely unchanged since I arrived at Barnard in 1978, taking a red-eye flight from Seattle by myself. The other students I encountered on campus seemed foreign to me. Their parents had gone to Ivy League schools; they played tennis. I had never before been east of Nebraska. My mother raised five children while she worked for the post office, and we kept a goat in our yard to reduce the amount of garbage we’d have to pay for at the county dump.

More:

In college, I read Richard Rodriguez’s memoir, “Hunger of Memory,” in which he depicts his alienation from his family because of his education, painting a picture of the scholarship boy returned home to face his parents and finding only silence. Being young, I didn’t understand, believing myself immune to the idea that any gain might entail a corresponding loss. I was keen to exchange my Western hardscrabble life for the chance to be a New York City middle-class museumgoer. I’ve paid a price in estrangement from my own people, but I was willing. Not every 18-year-old will make that same choice, especially when race is factored in as well as class.

As the income gap widens and hardens, changing class means a bigger difference between where you came from and where you are going.

Read the whole thing. There is lots of truth in this.

UPDATE: It turns out that Linda Tirado’s tale of poverty is pretty much untrue, or at least not the sob story she presented. And she has a history of lying online. Dr. Mary Russell found this takedown.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.