Murray Rothbard’s Practical Politics

Norman Singleton is Rep. Ron Paul’s legislative director. He has worked for Dr. Paul since 1997. Once a month, Norm and I meet at Bailey’s Pub & Grill in Arlington, Virginia to discuss two subjects—pro wrestling and libertarian politics.

The first is the primary reason for our meetings. Bailey’s offers monthly WWE pay-per-views, which we enjoy thoroughly over cold beer and chicken wings. It is by far the most serious subject we discuss.

Our discussions of libertarianism, or the Ron Paul-inspired “liberty movement,” to which Norm and I both belong, are always interesting. Norm is a die-hard libertarian. I am more traditionally conservative. How radical we are in our politics sometimes differs. How practical we are in advancing what some might consider “radical” politics does not.

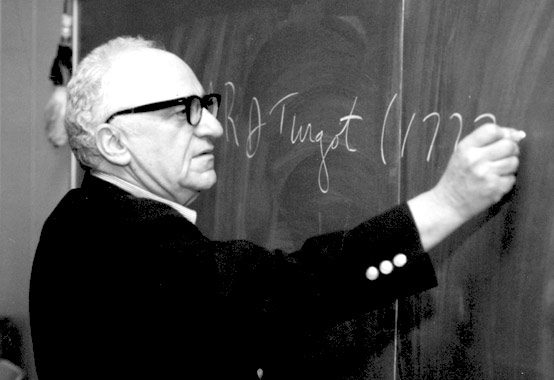

Austrian economist Murray Rothbard was one of the most brilliant libertarian minds of all time. Rothbard was also considered one of the most radical libertarians of his time. Today, Rothbard’s pure, unadulterated anti-statist philosophy is celebrated by libertarians as heroic and unequaled.

But Rothbard was also very practical about politics. Based on a recent discussion we’d had about the inevitable tensions that come with moving the liberty movement into the mainstream, Norm brought to my attention some old Rothbard columns from his personal collection.

While some radical libertarians eschew politics altogether, believing it compromises their philosophical purity, or that education alone will eventually bring a majority of people to the philosophy of liberty, Rothbard disagreed. He wrote in 1981:

I see no other conceivable strategy for the achievement of liberty than political action. Religious or philosophical conversion of each man and woman is simply not going to work; that strategy ignores the problem of power, the fact that millions of people have a vested interest in statism and are not likely to give it up…. Education in liberty is of course vital, but it is not enough; action must also be taken to roll back the State…

The above quote should be of no surprise to anyone remotely familiar with Rothbard. My favorite aspect of Rothbard is that for his entire life it was never enough to simply be more radical than his fellow libertarian—Rothbard wanted to take political action.

Politics is about making alliances, building coalitions, and marketing your message in a way that the masses can understand, digest, and embrace. If your purpose, intentionally or unintentionally, is to repulse or reject the masses, then there is no purpose to being in politics. If you’re not trying to make your ideas mainstream, then philosophy becomes a mere academic note. Wrote Rothbard:

For liberty to triumph in the United States (and eventually throughout the world) libertarianism must become a mainstream movement, converting if not a majority, at least a large, critical minority of Americans.

Rothbard not only helped found the Cato Institute, but also was heavily involved in the Libertarian Party in the 1970s and ’80s. In the early days of the Libertarian Party, Rothbard identified counterproductive personality traits or damaging tendencies that often afflicted his movement. A movement dedicated to questioning the state could sometimes detour into something closer to paranoia. A movement dedicated to being anti-establishment could devolve into its members rejecting societal norms as a matter of habit, thus situating itself as being against the American people themselves (voters).

Wrote Rothbard in 1987:

But here we face an inner problem and a paradox not only for libertarians, but for any radical, minority ideological movement. For marginal movements attract marginal people. Such movements are filled with what Germans call luftmenschen, people with no steady jobs, incomes, or visible means of support; the sort of people who instinctively alienate the mainstream bourgeois Americans, not so much by the content of their ideas, but by their style, lack of moorings, and “counterculture.”

Rothbard also observed how such movement types might react if presented with the possibility of tangible mainstream success:

If a serious opportunity should arise… for the movement to make a great leap into Middle America, into genuine influence in our society, that Libertarian luftmenschen will react not with enthusiasm but in fear and trembling. For far greater than their professed love of liberty is their hostility to bourgeois America.

Rothbard noted:

As one critical observer of the party has harshly charged: ‘they want the Party to be a social club for crazies.’

Finally, Rothbard wanted his fellow libertarians to ask themselves:

OK, do we want libertarianism to win, to make a big dent in America, or do we not? If we don’t want to win, why be in a political party at all? Why not simply form a social club and forget victory? And if we’re really devoted to liberty, how can we not do our best for liberty to win? Are we really libertarians, or are we just playing around?

This is more than a good question—it is “the” primary question for what Rothbard described as “any radical, minority ideological movement.”

Are we just playing around?

I’ve always thought that success for the liberty movement would be measured by how effective we are in making our ideas mainstream. I believe this view represents the majority of the liberty movement.

But I also believe there are those who see mainstream success as defeat. Rothbard not only vehemently disagreed, but believed these sentiments would forever be counterproductive to any potential political success. He was right. Rothbard also believed that some people, whether intentionally or temperamentally, simply have no intention or desire of ever achieving political success; they simply want to keep the movement to themselves, and for themselves, for no discernible purpose other than reinforcing their own philosophical identity. In identifying and attacking this character trait, again, Rothbard was right.

Minority ideological movements can have great success. Rothbard believed this his entire life. But to achieve success they must become something more than minority ideological movements. Thanks to Ron Paul, the liberty movement is currently achieving great success. Some will inevitably continue to see this success as defeat.

Murray Rothbard would not have been among them.

Jack Hunter is the co-author of The Tea Party Goes to Washington by Sen. Rand Paul and writes the Paulitical Ticker blog for the Ron Paul 2012 campaign. The views presented in this essay are his own and are independent of any campaign or other organization.

Comments