Macron Haunted by the ‘Ni, Ni’

On Thursday morning lycée students were out protesting in the streets of Paris. In districts that were once “populaire” and have now been gentrified by the new “boboisie” (David Brooks’s coinage “bobo” still resonates in France), they first blocked the doors to their schools (but were considerate about letting enter those in who had important exams to prepare for), then joined forces for a march toward the Bastille. It was a “ni, ni” or “neither, nor” march, young students suddenly awakened to the fact that France’s presidential choice had boiled down to a contest between “racist” Le Pen and the “banker” Macron. One of their placards, much streamed on TV news, was “Ni Patrie, Ni Patron“—“No Country [or perhaps “Homeland”], No Boss.” (I think it doesn’t hurt Marine Le Pen to represent the “homeland” side of this diptych.)

France is entering what some call a demographic crisis; parts of Paris seem to have been taken over by African-refugee street people, and some nearby suburbs have been quite thoroughly Islamicized. But the 18-year-old protesters marching on a school day between République and Bastille chanting leftist and anarchist slogans are as white as can be.

This is a reflection of the emerging social reality in France, which has been developing for years and has been spelled out by the geographer-sociologist Christophe Guilluy, whose work has made him the all-but-officially-acknowledged guru of this election. France is increasingly divided between the winners of the globalized economy and the losers—a new division that is now more important than the traditional “left-right” divide. The winners are concentrated in Paris and other major cities and work in fashion, design, or the knowledge industries and are linked to the world markets. There is some subsidized housing in the metropole to ensure the presence of “key workers”—cops and firemen especially—but the rest of the white working and much of the lower middle class has been priced out of the city. The service workers, those who clean apartments and cook meals and drive cabs are, for the most part, immigrants, and live in the huge public-housing blocs that surround the Paris. For Guilluy, these segregated housing developments represent a kind of government-subsidized “maid quarters” for the service employees of the new boboisie, a reference to the way the 19th-century bourgeois buildings were constructed, with grand apartments and a separate stairwell leading to a cluster of small rooms where cooks and maids could live near to the families that employed them. The white working class that once made the near suburbs a Communist Party stronghold has more less abandoned them, or been driven out, according to one’s interpretation.

The point is, to live in Paris now, or certainly to raise children there, you have to be well-off. So the kids out chanting the other day, with a little bit of window-breaking and fighting the cops thrown in, were more of less the class equivalent of children from The Dalton School chanting “no to racism,” “no to bosses.” But it’s France, so kind of typical.

Macron, by the way, scored 35 percent in the 11-person first-round race in Paris, while Marine Le Pen got less than 5 percent of this vote. That kind of division—in less stark terms—is reflected in the returns all over France: Macron does well in the French metropoles, which have benefited from globalization; Le Pen, whom I believe did not win a single city over 100,000 people (though she came in a close second in Nice and Marseille), does well in the la France peripherique, rural regions that have been generally the losers from globalization.

There is a political importance to the “ni, ni” slogan—for the only possible avenue for Marine Le Pen to win, or even to make it close, is for there to be massive abstention or blank voting (where you go to the polls and write in Charles de Gaulle or Maurice Thorez on your ballot). The candidate of the right-wing business classes, François Fillon, fell in line quickly and endorsed Macron, and so did all of the candidates he had bested previously in the LR (or Les Républicains) primary, including former heavy-hitters Alain Juppé and Sarkozy. There were occasional holdouts; Marie France Garaud, a veteran Gaullist advisor to Pompidou and Chirac, has endorsed Marine Le Pen, and many LR voters attended the Le Pen rally in Nice last night (according to French TV). But most of the French political class has lined up against Le Pen.

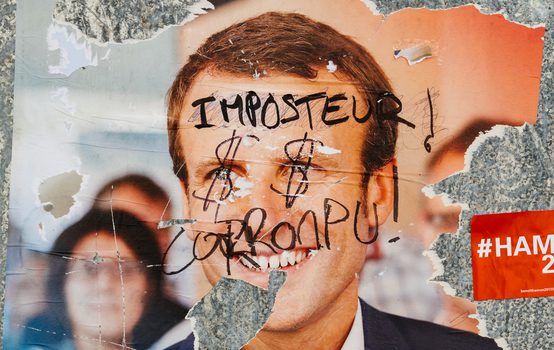

Not everyone however. If the “right” fell quickly in line, the leading left candidate, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, has been more coy. He has announced he will speak to his voters over YouTube later today, but rumor has it he will tell them to abstain, or vote blank, or vote Macron according to their conscience. In other words, no reason for pro-communist voters to rush out and give a large landslide to the former Rothschild investment banker. There’s a film clip on the internet of a younger Marine Le Pen and Mélenchon fighting with one another on TV 15 years ago, and if you look at it you might well conclude that they don’t completely hate one another.

In any case, the young kids’ “ni, ni” represents a significant current in this election, which could matter in determining the outcome.

Marine Le Pen is a vastly superior candidate to Donald Trump. She knows the issues and she works hard, and there’s not the slightest reason to think (as there now may be with Trump) that she isn’t committed to her campaign positions. But the structural differences between what Trump faced in the fall of 2016 and Le Pen’s challenge now are large. Trump captured the Republican nomination, which ensured that a great many Republican officials would endorse him—they more or less had to for the sake of their own political skins. What if he’d received no Republican support apart from that which he had managed to gather by the end of February? What if every Republican senator save two had explicitly endorsed Hillary? That gives a sense of the uphill road Le Pen faces.

The latest polls have tightened somewhat—one published yesterday had Le Pen at 41 percent, which represents a three-point bump since last Sunday’s election. The press is still full of speculations that Macron (“little Macro” I cannot resist calling him) has gotten off to a poor start, and has to do better to make contact with voters, etc. I’m sure he will; for all his many flaws, he’s not dense. But what is at stake is the nature of the French right—whether it will led by the National Front and its allies, whether Marine Le Pen will be unofficial leader of the opposition. Many in the France establishment just wish the National Front would be forced back into its hole so they could revive the nonsense of a Front Républicain (a noxious and dishonest phrase which seeks to deny democratic legitimacy to the National Front’s issues and voters). That doesn’t look like it’s going to happen. And then there’s a televised debate next Wednesday night, four days before the vote. You can be sure that Macron’s supporters wish there were some way their candidate could duck that one.