Winston Churchill: Randolph’s Son and Father

Churchill & Son, by Josh Ireland (Dutton: 2021), 464 pages.

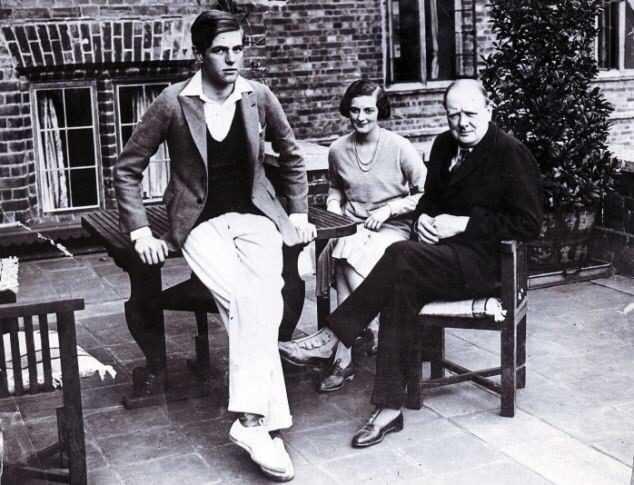

In its charming Englishness, the title of the new dual biography Churchill & Son has something of the flavor of a boutique law firm, a shoe repair shop, or, possibly, a novel by Charles Dickens, but in fact it serves as a potent reminder of a most striking fact: Winston Churchill, among the most robust, combative, and, frankly, masculine of 20th-century political figures, had, among his five children with his wife Clementine, just a single son, his second-born, Randolph.

For a man of the energy and temperament of Churchill, two or three or five sons would have seemed to better fit the bill: One can imagine a gaggle of Young Winstons bouncing off the walls at home, helping Winnie lay bricks or prepare speeches to Parliament. Instead, Randolph, as the lone male offspring, was called upon to serve as the solitary vessel for his father’s notions about fatherhood, manhood, and family ambitions. For father and son alike, it turned out to be a burden.

Such is the argument advanced in Josh Ireland’s robustly researched, eminently readable new book, which retells many of the signal events of Winston’s life, service, and exploits through the prism of his relationship with Randolph. “When Winston looked at Randolph, he knew that he had given him, or encouraged within him, the best elements of his own personality: kindness, originality, eccentricity, heedless bravery, and a flamboyant disregard for anybody else’s opinion,” writes Ireland, who quickly adds—and whose book amply demonstrates—that there were downsides to the Churchill inheritance, too. “He would also have seen colossal faults: arrogance, recklessness, an uncontrollable temper, and a perplexing weakness for self-sabotage.”

Seeking to trace the history of Churchill’s paternal preoccupation, Ireland revisits Winston’s own childhood of seeking to win favor with, or simply the attention of, his own father, Lord Randolph Churchill, whose dynamic manner and impressive C.V. (Leader of the House of Commons, etc.) masked a tactless parenting style. “Lord Randolph barely seemed to notice his son; he did not even know how old he was,” Ireland writes. “When he did take time to speak to him, it was to upbraid him for his faults.”

Yet, as a boy, Churchill maintained a reverent attitude about his distant dad (“He bought a scrapbook and pasted into it the cartoons in which ‘Randy’ was depicted”), one that persisted in spite of so many dashed dreams: Ireland writes plaintively of 13-year-old Winston’s plans for a festive family Christmas being upended upon learning that his parents intend to tour Russia for a few months instead.

Even as a grown man, though, Churchill declined to partake in the modern temptation to blame his upbringing for every reversal or character flaw. To the contrary, Churchill came to feel something good and lasting could result from children being brushed-off or snubbed by their parents. “A boy deprived of a father’s care often develops, if he escapes the perils of youth, an independence and vigor of thought which may restore in after life the heavy loss of early days,” wrote Churchill, who, in 1906, would pen a properly admiring biography of his father.

Nonetheless Churchill adopted a different parenting strategy when it came to his own brood, particularly his son (and his father’s namesake), Randolph, who was born in 1911. “He was unusually determined to involve himself in day-to-day family life,” Ireland writes of Winston. “He kept a jealous watch on nursery life, and his letters are full of delight at his babies’ growth, and in noting their mannerisms.”

While Winston’s overly generous approach to childrearing was benign in and of itself, it seems to have instilled in his male heir a certain full-throated obnoxiousness. Simply put, Randolph, given a wide berth by his indulgent pop, gradually morphed into a little devil and then a larger devil. “Slapping him made no difference; he even used to confess to crimes he had not committed so he could show that nothing they could do would affect him,” Ireland writes, referring to the futile efforts of nursery maids to corral the youngster.

History was repeating, or at least rhyming with, itself: Although Winston and his father, Lord Randolph, differed in their approaches to fatherhood, both produced sons who rewarded them with hero worship. Winston egged on Randolph’s verbal combativeness and instinct for argument. Is it any wonder that the lad found that school days at Eton couldn’t compare with dinner conversation at home among the likes of David Lloyd George and Max Beaverbrook?

It would be pleasing to say that this odd childhood—equal parts infantile (in Winston’s tolerance for Randolph’s bad behavior) and mature (in Winston’s welcoming Randolph into his sphere)—produced a man of great character and depth, but much of the book is taken up with accounts of Randolph’s severe limitations.

Randolph was rash with finances (“Spending money, spending lots of it, was an addiction Randolph could never shake off”), and flat-out hard to get along with, even with his beloved dad. His father could maintain civility with those with whom he disagreed (even on matters as consequential as Appeasement), but Randolph had no such inclination towards temperance. “Randolph either did not care or could not control himself,” Ireland writes. “Even more than Winston, he saw the world in black and white.” In 1939, Randolph married Pamela Digby, producing, to Winston’s glee, Winston S. Churchill: “Winston was so proud of this child who would carry on the family name that he would sometimes stand and watch as Pamela nursed him.” Even here, though, Randolph came up short: the marriage sputtered to an end, Pamela took up with Averill Harriman, and much family in-fighting commenced. “The impudence of youth had been succeeded by a deplorable cruelty,” Ireland writes of Randolph’s later years.

There were compensations: As with Joe Biden and his indefatigable, multi-decade pursuit of the presidency, Randolph was undeterred by several failed campaigns for Parliament, securing his own seat from 1940 to 1945. He served during World War II. Yet, by the time his father’s first term as Prime Minister concluded in 1945, the consensus was that the Churchill dynasty had exhausted itself. Winston, Ireland writes, “had become a figure so titanic, so glorious, that there was no need for the next generation to preserve his legacy.” This judgment is bolstered by the fact that, in the years before his death in 1968, Randolph, a working journalist whose greatest inheritance from his father was his writing ability, had commenced the most lasting endeavor of his life: naturally, memorializing Winston (who had died in 1965) by penning a biography. The gadabout had become a stickler: “As the chapters-in-progress were read to him, he checked and rechecked his facts,” Ireland writes.

You might call Churchill & Son an entrant in the “stage mother” genre of nonfiction—that is, if the “stage” was Western civilization and the “mother” was, well, Winston Churchill. Indeed, the book comes with all the cautionary tales of most accounts of stage parenting, implicitly warning against parents who expect too much of the next generation, who, more often than not, can’t quite deliver. In the end, then, this is a gloriously entertaining family soap opera set against the sweep of history.

Peter Tonguette writes regularly for the Wall Street Journal, Washington Examiner, and National Review.

Comments