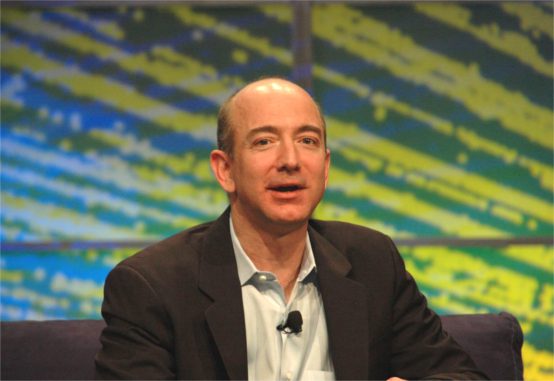

Will Jeff Bezos Destroy the “Village” in Order to Save It?

So why did Jeff Bezos buy The Washington Post?

While I’m sure that it will be helpful to Jeff Bezos’s sales-tax-related lobbying to have a major national newspaper in his wallet, I am quite skeptical that this was an important motivation for purchasing an asset like Post, for a variety of reasons. There are easier and cheaper ways to get legislation passed, for one. Bezos was already well-positioned to influence the Democratic party on an issue like this. And buying a newspaper raises Bezos’s profile – which isn’t always the best way to get your way in a highly partisan environment. (Will Republicans be more likely to support him on his pet issue if the Washington Post starts editorializing in its favor?)

But the most important reason this viewpoint is wrong, I think, is that it’s small ball. And the one game Jeff Bezos never plays is small ball. (Full disclosure: I briefly worked with Bezos before he founded Amazon, but we didn’t work closely together and I didn’t get to know him particularly well. We had lunch once. Woo-hoo.)

Perhaps Bezos bought the Washington Post in order to advance a larger ideological agenda. But apart from a general techno-libertarian orientation, we don’t know that much about what Bezos believes. Or, it might be that Bezos is just tickled by the idea of owning a major newspaper – that it’s the equivalent of buying a major sports team. The purchase makes him a player on a new stage.

I’m skeptical of these viewpoints as well. Bezos isn’t Mark Cuban; he has no reason to be looking for a new stage to play on. And if he were a political animal, we’d have seen more evidence of that fact before now.

I would assume that one reason Bezos bought the Post is simply that it was available for sale. Like Park Avenue coops, news organs with that kind of pedigree don’t come on the market all that often. Bezos’s announcement that he has no plans to change the management at the Post might be entirely accurate: he has no plans, yet, because he bought the paper first, and will figure out what he wants to do with it in good time. There are certainly enough small reasons – the cheap price, the value of a friendly editorial page, the opportunity to study a major newspaper’s physical delivery system – to justify the transaction, which isn’t a major financial risk to someone of Bezos’s wealth anyway.

But the real risk Bezos is taking isn’t financial – it’s reputational. Bezos is a true visionary who likes to be known as such. The proper expectation anyone should have looking at this transaction is that Bezos plans to reinvent the newspaper business. He would know that. Therefore, I would guess the primary reason he bought the paper is to prove that he, Jeff Bezos, is capable of doing what basically nobody else has quite figured out how to do: save journalism.

How might he do that? Well, the first thing to realize is that the crisis of contemporary journalism isn’t due to the fact that you can’t sell ads anymore. The crisis is due to the fact that the the natural vertical integration of the news business has unraveled as a consequence of technological developments – and historical accident.

Allow me to defend that proposition before moving on to my thoughts on what one could do with the Post. Classified ads were a mainstay revenue source for most newspapers before the advent of Craigslist, and the loss of classified ads has been devastating to newspaper revenue. But logically, if customers primarily wanted access to the ads, and weren’t willing to pay for access to journalism, someone would have asked long ago why they were including journalism at all. Surely a paper that focused entirely on advertising would be more profitable.

And, in fact, there are plenty of examples of this sort of product in the magazine world, so I’m not arguing that nobody thought of this. I’m arguing that the fat profits newspapers garnered in the golden years were the reward for creating an appealing product. That is to say, something people were willing to pay for.

And people are still willing to pay for it today. Huge numbers of people spend a very large amount of time reading one or another variety of news on the internet. They pass news stories around on email and through Facebook. And they pay handsomely for the privilege. They pay their cable company, or their phone company, or their wireless carrier – most likely, they pay multiple service-providers so that they can access the information they want, including journalism, from a multitude of devices, which they also pay for. And I think it’s safe to say that few people would pay a comparable price for access to the internet if they couldn’t view the sorts of information that newspapers traditionally provided.

The problem, then, is that the content aggregators don’t own the pipes. Whereas, in the days of the vertically-integrated newspaper, they did.

For further proof of my point, take a look at the Bloomberg media empire. The cornerstone is the Bloomberg terminal (which is now frequently a virtual device rather than a piece of dedicated hardware). This is a delivery service for financial data and a huge suite of analytical tools, which has made it a must-have for anyone who’s anyone on Wall Street.

But to protect the value of that relationship, it behooves Bloomberg to provide as many reasons as possible to keep looking at their terminals, rather than using other services. That’s why you can read movie reviews, send text messages, check airline flight times, and perform a zillion other functions on a Bloomberg terminal – functions that don’t generate incremental profit for Bloomberg. Because they make it harder and harder for any competitor to convince one of their customers to switch to a cheaper (even free) alternative. Bloomberg’s entire news operation is arguably a service that simply enhances the value of the combined product, and thereby raises the barrier to competition, rather than something that could be profitable on its own, severed from the data-and-analytics package. Bloomberg owns the pipe, and they want you to keep paying for access to the pipe, so they try to shove as much valuable stuff through that pipe as possible. Which is pretty analogous to the way newspapers worked in the old days.

Normal humans, of course, get much of their news on the “free” internet, and the owners of the pipes to the internet don’t generally produce much in the way of content. Instead, they keep the gates open to all the content anybody wants to put out there. They don’t have a business unless somebody does put it out there. But they don’t have any business reason to downstream their revenues to content providers. Let them figure out how to collect revenue.

Collecting revenue for specific content is extraordinarily difficult, though, not so much because that content is competing with free as because charging for content limits that content’s distribution – and because in many cases wide distribution is part of what makes the content valuable. But effective aggregators have a considerably better value proposition. An aggregator provides an essential editorial function, helping users find what they want but also helping them to learn what they want, based on some combination of knowledge about the user, knowledge of what’s out there, and knowledge of what’s worth wanting (i.e., having a sensibility that compels respect). In effect, a good aggregator creates a kind of parallel internet. They turn their service into a pipe-within-a-pipe. And that can be monetized if it gets big enough, and customers are loyal enough.

What I’m proposing, basically, is that The Washington Post should do what Yahoo has been doing, but in reverse. Yahoo, a once-mighty content aggregator, has been reinventing itself as a news organization, a content-creator, recognizing that it needs to have some actual content to push through its “pipe” of aggregation. Of course, Yahoo is a pretty downmarket brand, and their journalistic efforts have developed accordingly. The Washington Post is a considerably more elite brand. If I were reinventing it I’d be asking what an elite-brand aggregator would look like, and what it would take to make the paper’s digital portal into a key place where the customers it wants turn for the kinds of information they are always looking for. That information might be generated by the Post – but most if it would not. The newsroom would only be one component of the operation – but a critical one, because the key transition is to turn users into subscribers, which means you need some content that they need to come to you to get.

Think about what Netflix has been doing. They started out as a subscription service providing a wide variety of video content – a much bigger variety than any video rental place could. On that basis, they turned themselves into a huge business that drove the nail into the coffin of Blockbuster and the like – and a subscription business, the best kind of business, where you collect money directly from customers whether they ultimately use the service a lot or a little. But they always knew that the physical delivery mechanism of DVDs wasn’t the future; the future was digital streaming. And that put them at the mercy of the owners of the content, who might prefer to capture the bulk of the revenue themselves – or to create competing services.

So Netflix needed its own content, and, with “House of Cards,” “Orange Is The New Black,” etc., has started creating it. Even if that content is great, it still won’t be reason enough to subscribe to Netflix – not if that’s all you get. But if you get a wide variety of third-party content, plus a good interface, plus you get a handful of shows that you can only see by subscribing to Netflix – well, now there’s a reason to subscribe, either instead of or in addition to other services. And once you have a loyal subscriber base, you are in a stronger position to negotiate with third-party content providers – you don’t just need their content; they need your customers.

I don’t want to get hung up on the details of this – whether you monetize subscribers by selling subscriptions or by selling access to advertisers; whether a subscription means some content sits behind a paywall or whether it means some services are unavailable – because those questions aren’t the heart of the matter. The heart of the matter is how you think about the place of journalism – real journalism – within the context of a larger digital business.

If The Washington Post treated its own newsroom as a premium product to be bundled with a larger package of services that mostly re-purpose third-party-generated content – and long-form investigative journalism in particular is a perfect example of a premium product that is very hard to sell on its own, but which considerably enhances the value of a more comprehensive bundled product – then its scope could be much, much larger than it could ever be on its own. Larger, and more truly national, in fact, than The New York Times is (and the Times has already gone some way in the “parallel internet” direction, but relying on its own prodigious capacity to generate content). And the Post has a sufficiently powerful brand – still – that its determination of what content is worth investing time in would be more trusted right out of the gate than, say, these guys. (And those are the guys who just bought Newsweek.)

Jeff Bezos, meanwhile, has just the right experience from his work building Amazon, just the right orientation about balancing the competing goals of quantity and quality while advancing both, and the patience to work for the long term to make a reinvention of this sort work. Amazon, of course, didn’t buy the Post, but it would be bizarre if the paper didn’t benefit from Bezos’s experience in creating communities, data-mining customer behavior, integrating third-party providers into a single digital delivery platform – all of which will be essential if the Post is to be reinvented as something more than a newspaper.

My own personal hope is that Bezos becomes the first internet media mogul to actually downstream revenue to third-party content providers. I’m sure it wouldn’t be much, but even establishing the principal would be huge. And the opportunity to capture a huge portion of the high-value journalistic internet is enormous. Who wouldn’t rather optimize their blog to integrate with the Washington Post‘s engine than try to sell enough banner ads to keep the lights on? And once that process has begun, the “parallel internet” starts working better than the real thing.

I’m not a techno-utopian – far from it. But if you care about newspapers – or, more correctly, about journalism – then you have to know that the industry isn’t going to be saved by someone who loves newspapers. Nor it is going to be saved by someone who is very focused on the short-term bottom line. I don’t know if it can be saved by Jeff Bezos, but he’s a better horse to bet on than most.

And Jeff, if you’re interested in talking further, I’m usually available for lunch.

Comments