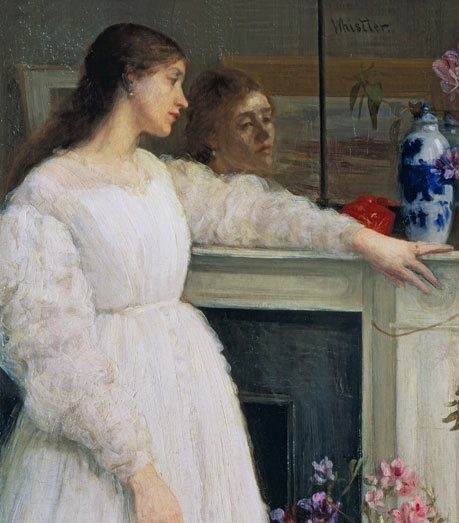

When Jimmy Met Jo

What mattered to Whistler about his art was not the subject but the emotions stirred in the viewer.

The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler, National Gallery of Art, until October 10, 2022

The partnership between Joanna Hiffernan (1839–1886) and James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) in the first decade of the painter’s career created some of the most beautiful and influential art of the century. The world’s leading Whistler scholar, Margaret MacDonald, always regretted that Hiffernan never got the attention she deserves. The new National Gallery of Art exhibit, curated by MacDonald and the Gallery’s American Art curator Charles Brock, aims to correct that wrong. The exhibition features most of the oil paintings, drawings, and etchings in which Hiffernan appears as well as a few surviving letters and documents. As a result, Hiffernan’s story is told in more detail, with far greater sympathy, than that of the artist himself.

Comments