Walker Percy’s Funny and Frightening Prophecy

Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins: The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World, a finalist for the 1972 National Book Award, remains even more acutely prophetic now than when it was published almost five decades ago. “The novel is not saying: Don’t rock the boat, cool it, be moderate, vote moderate Republican or Democrat,” Percy declared at the NBA awards ceremony. “No, it rocks the boat. In fact, it swamps the boat.”

William F. Buckley Jr. wryly suggested that all future presidents should be required to swear a double oath of office: not only to uphold and defend the Constitution but also to have read, marked, learned, and digested Percy’s Love in the Ruins. “It’s all there in that one book,” said Buckley, “what’s happening to us and why.” Indeed, Percy’s novel reads as if it were written in anticipation of the 2016 presidential election.

“A serious novel about the destruction of the United States and the end of the world,” Percy declared, “should perform the function of prophecy in reverse. The novelist writes about the coming end in order to warn against present ills and so avert the end.” He isn’t writing as a biblical prophet, but neither can he deny that his allegiances are fundamentally Christian. His own vision of reality is confessedly “incarnational, historical, predicamental.” In an increasingly pagan and hostile age, Percy doubted the efficacy of a serene Christian humanism. Better to serve as the canary in the coal mine, so as to detect the asphyxiating gas that sickens unto death.

Like his fellow Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor, Percy believes that the novelist “should shock … his readers by speaking of last things—if not the Last Days of the Gospels, then of a possible coming destruction, of a laying waste of cities, of vineyards reverting to the wilderness.” Percy adds, “Unlike the prophet, [the novelist] does not generally get killed. More often he is ignored.” Already one can detect Percy’s irony within his gravity. He is not writing in the fashion of Orwell or Huxley, depicting totalitarian or technological nightmares. Love in the Ruins concerns a cataclysm that doesn’t happen. It’s a country club apocalypse, a lawn party catastrophe.

♦♦♦

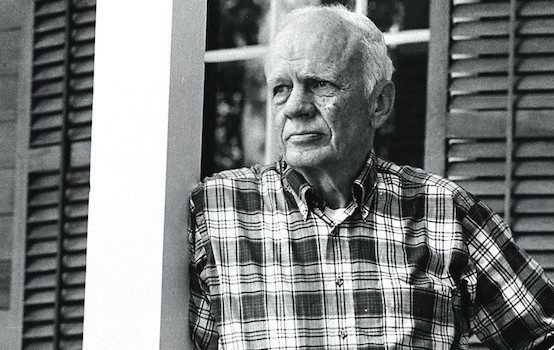

Walker Percy (1916-1990) was a non-practicing physician who never lost his desire to “thump the patient and figure out what’s wrong.” He also wanted to know what went wrong with America, the country Lincoln called man’s “last best hope.” How and why have things fallen apart? Percy transfers his befuddlement to his narrator/protagonist, Dr. Thomas More, a psychiatrist living and working in Paradise Estates, a dubiously named subdivision of a New Orleans suburb. More gets his own name from Sir/Saint Thomas More, the Catholic humanist and martyr.

Unlike his eponymous forebear, this latter-day More is neither gentlemanly nor godly. His life is a mess, as he drolly confesses: “I love women best, music and science next, whiskey next, God fourth, and my fellowman hardly at all. Generally I do as I please. A man, wrote John, who says he believes in God but does not keep his commandments is a liar. If John is right, then I am a liar. Nevertheless, I still believe.” In that final sentence, Percy offers a scintilla of hope that something good may emerge from this suburban Armageddon set sometime around 1983, on the brink of Orwell’s apocalyptic year.

The poor U.S.A.!

Even now, late as it is, nobody can really believe that it didn’t work after all. The U.S.A. didn’t work! Is it even possible that from the beginning it never did work? that the thing always had a flaw in it, a place where it would shear, and that all this time we were not really different from Ecuador and Bosnia-Herzegovina, just richer. …. What a bad joke: God saying, here it is, the new Eden, and it is yours because you’re the apple of my eye, because you the lordly Westerners, the fierce Caucasian-Gentile-Visigoths, believed in me and in the outlandish Jewish Event, even though you were nowhere near it and had to hear the news of it from strangers. But you believed it and so I gave it all to you, gave you Israel and Greece and science and art and the lordship of the earth, and finally even gave you the new world that I blessed for you. And all you had to do was pass one little test, which was surely child’s play because you had already passed the big one. One little test: here’s a helpless man in Africa, and all you have to do is not violate him. That’s all.

One little test: you flunk! …

Flunked! Christendom down the drain. The dream over. Back to history and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Tom More here names chattel slavery and its dread aftermath as the flaw in the American fabric that has caused it finally to shear. Who can doubt that racial injustice, with its sorry continuing legacy, remains the distinctive American sin? And as if there were any lingering dream of American exceptionalism, Wendell Berry claims that our destruction of Native Americans amounts to our own holocaust. Percy identifies slavery as “the egregious moral failure of Christendom. It is significant that the failure of Christendom in the United States has not occurred in the sector of theology or metaphysics … but rather in the sector of everyday morality.” When Tom More quotes from 1 John about his own mendacity in failing to keep God’s commands, he surely remembers this codicil: “for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not seen.” Hence Percy’s own confession in an essay about Love in the Ruins: “White Americans have sinned against the Negro from the beginning and continue to do so.”

Yet America’s racial sins are peripheral to the novel. While the narrative is set in Louisiana, it offers no searing indictment of the Southern sins, such as can be found in William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. The race riots of the 1960s, especially the burning of the metropolitan ghettos, were sufficient signs that the racial problem that was once regional had become national. “It’s not that the South has got rid of its ancient stigma,” Percy writes, “….It’s rather that the rest of the country is now stigmatized and is in even deeper trouble.”

Percy’s philosophically astute psychiatrist identifies this far deeper trouble in a single lapidary claim: “Descartes ripped body loose from mind and turned the very soul into a ghost that haunts its own house.” Dr. More traces our illness to René Descartes, the 17th century French philosopher whose notorious motto was “Cogito, ergo sum: I think, therefore I am.” Descartes’ animating idea marked a fundamental “turn to the subject,” a relocation of ultimate authority in subjective human consciousness rather than any transcendent reality.

It is safe to say that, prior to Descartes, human reason seated itself either in the natural order or else in divine revelation. In the medieval tradition, reason brought these two thought-originating sources into harmony. Thus were mind, soul, and body regarded as having an inseparable relation: they were wondrously intertwined. So also, in this bi-millennial way of construing the world, was the created order seen as having multiple causes—first and final, no less than efficient and material causes. This meant that creation was not a thing that stood over against us, but as the realm in which we participate—living and moving and having our being there, as both ancient Stoics and St. Paul insisted. The physical creation was understood as God’s great book of metaphors and analogies for grasping his will for the world.

After Descartes, by contrast, the sensible realm becomes a purposeless thing, a domain of physical causes awaiting our own mastery and manipulation. Nature no longer encompasses humanity as its crowning participant. The soul drops out altogether and is replaced by disembodied mind. Shorn of its spiritual qualities, the mind becomes a calculating faculty for bare, abstract thinking. To yank the mind free from the body is also to untether it from history, tradition, and locality. After Descartes, the mind allegedly stands outside these given things so as to operate equally well at anytime and anywhere. Insofar as belief in God is kept at all, it is an entailment of the human. Atheism was sure to follow. Marx made truth itself a human production, whether social or economic. Nietzsche went further, insisted that nothing whatever can stand over against the human will to power, not even socially constructed truth. Hence the cry of Zarathustra: “If there were gods, how could I endure not to be a god!”

♦♦♦

This double revaluation of mind and nature that began with Descartes resulted in a radically new conception of human freedom as sheer individual autonomy, the right to determine one’s own identity and destiny. Hence our ever-greater disregard for communal responsibilities and obligations—except for those that, in our sovereign subjectivity, we select for ourselves. Until recently, such potential hyper-individualism was held in check by our reliance on a generalized set of religious beliefs and moral practices to which most people gave their consent, if vaguely. These universal first principles provided the constraints and directives that enabled human beings to flourish or fail. Such classical liberalism undergirds all Enlightenment democracies. But now these checks and balances have been largely removed. The triumph of sovereign subjective preference has resulted in what Percy called “a tempestuous restructuring of consciousness,” a shift in human existence that amounts to the invention of a virtually new species. Percy calls it “a strange Janus monster,” both haunted and paralyzed with self-transcendent longings and fears that mere animals do not experience.

Love in the Ruins locates this strange new creature on the progressive left no less than the regressive right. Our alleged opposites are in fact cohabiting twins. Percy refuses to treat these bedfellows with grave solemnity, dignifying them with an undeserved seriousness. Instead of waging a proleptic culture war, he resorts to raucous ridicule and withering satire of both right and left.

Consider, for example, Tom More’s report that the Roman Catholic Church has been hijacked by the radical right and renamed the American Catholic Church, now headquartered in Cicero, Illinois. Its logo is defined by an image of a suburban house surrounded by a white picket fence. It celebrates Property Rights Sunday, and the American flag is raised at the consecration of the Host. So have the old Republicans adopted an infamous phrase from Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential nomination speech as the basis for their new name. They call themselves the Knothead Party. They have distributed millions of buttons reading “Knotheads for America,” and they wave banners proclaiming, “No Man Can Be Too Knotheaded in the Service of His Country.” These same Knotheads have enacted laws requiring compulsory prayers in the all-black public schools, while also making funds available for birth control in Africa, Asia, and Alabama. Conservative Protestants, in turn, devote themselves almost entirely to entertainment, as Percy prophesies the rise of the theatrical megachurches. These comfy evangelical clubs have developed golf courses that can be played at night, “under the arcs.” Their slogan is “Jesus Christ, the Greatest Pro of Them All.”

Political and religious liberals fare no better. Catholics on the left are agitating for the right of divorced priests to remarry. One of these priests, Father Kev Kevin, operates the orgasm console of a sex clinic, as salvation has shifted definitely downward. Liberal Protestants nowhere appear, perhaps because they have been absorbed into the Democratic Party. Like the Republicans, these new Democrats have chosen a new label; they call themselves simply “the LEFT.” They have shortened their acronym from the original LEFTPAPASANE: “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, The Pill, Atheism, Pot, Anti-Pollution, Sex, Abortion Now, Euthanasia.” Their chief political accomplishment is to have stricken “In God We Trust” from pennies.

Both camps rely on proctology as the reigning medical science in this brave new America. The liberal ailment is diarrhea, since liberals can’t hold on to anything. The conservative complaint is constipation, of course, since conservatives won’t let go of anything. Tom More declares a plague on both of their colon conditions, making wry reference to William Butler Yeats’s celebrated poem, “The Second Coming,” where Yeats prophesied the monstrousness that will be loosed upon any land where the center does not hold, despite the outward signs of health and prosperity:

The center does not hold.

However the Gross National Product continues to rise.

There are Left states and Knothead states, Left towns and Knothead towns but no center towns…. Left networks and Knothead networks, Left movies and Knothead movies. The most popular Left films are dirty movies from Sweden [e.g., depicting fellatio being performed in mid-air by parachutists.] All-time Knothead favorites, on the other hand, include The Sound of Music, Flubber, and Ice Capades 1981, clean movies all….

Percy was vexed with the question of how properly to name our Cartesian sickness unto death. Repeatedly he lamented that our theological and political vocabulary has lost its purchase. Sin and salvation, grace and redemption, are coins whose faces have been worn slick by a devaluing overuse. Thomas Merton put it well when he said that the command to “Love God” has no more force than “Eat Wheaties.” Neither is there any moral trenchancy left in such phrases as “the dignity of the individual,” “the quality of life,” “self-evident truths,” much less “Nature and Nature’s God.” Such phrases have slipped whatever metaphysical moorings they may once have possessed.

How to name it? As an astute reader of Kierkegaard, Percy invented a new set of diagnostic terms derived from The Sickness Unto Death. Kierkegaard had also sought fresh metaphors for ultimate matters, and so he spoke of despair rather than sin, seeking to enliven a vital term that had been worn slick by familiarity. Authentic selfhood thus became Kierkegaard’s synonym for salvation. Despair, by contrast, signifies damnation. Original sin is manifest not in immoral acts so much as in refusing to become a true self existing transparently before God. Percy, in turn, identifies the twin forms of inauthentic selfhood (despair) as angelism and bestialism. Accordingly, Dr. Thomas More examines his patients as being afflicted with one or the other of these twin Cartesian conditions.

More’s angelic patients, for instance, have attempted to re-invent themselves out of whole cloth, floating untethered in the realm of infinite possibility, denying their created condition as finite and embodied souls. They abstract themselves from the traditions and convictions that root them in time and place, becoming virtual angels hovering above the earth. His bestial patients, by contrast, seek to plunge beneath their condition as ensouled bodies by living in consumerist contentment, immuring themselves in comforts and conveniences, money, and possessions.

As his satirical name suggests, Ted Tennis is a gameplayer, an overly intellectual graduate student so obsessed with the theoretical possibilities open to him that he orbits the earth in sheer angelic abstraction. Rather than making husbandly love to his wife Tanya, he quakes with terror at having sexual intercourse, fearing that he could not (to use his words) “achieve an adequate response.” He thus hopes that Dr. More will fit him with a penile “training organ” that will cure his impotence. Instead, More assigns him an ordeal of immersion into radical finitude and utter unselfconsciousness. Rather than sending Tennis straight back to Tanya, gliding along the interstate in his bubble-like sports car, More insists that he walk home through the dense undergrowth of a boggy bayou. More hopes to reel Tennis back to earth from his seraphic abstraction. The result is wondrously and comically efficacious:

The six miles took him five hours. At ten o’clock that night he staggered up his back yard past the barbecue grill, half-dead of fatigue, having been devoured by mosquitoes, leeches, vampire bats, tsetse flies, snapped at by alligators, moccasins, copperheads … set upon by a couple of Michigan State dropouts on a bummer who mistook him for a parent. It was every bit of the ordeal I had hoped…. So it came to pass that half-dead and stinking like a catfish, [Ted] fell into the arms of his good wife Tanya, and made lusty love to her the rest of the night.

As his name indicates, P.T. Bledsoe is one of P.T. Barnum’s pathetic “suckers” whose very soul is hemorrhaging in bestial rage, despite his considerable business success. He is so sunk in finitude and necessity that he believes that the world is closing in on him, threatening him on all sides. He has turned paranoid, convinced that everyone is out to “get” him. A hardcore Republican who despises Jews and blacks, Bledsoe wants to relocate to Australia so as to preserve his hard-earned wealth and pure bloodlines. It’s clear that Bledsoe is barely a self at all, since he has no consciousness of his despair, the real cause of his misery. Dr. More comically recommends that Bledsoe emigrate to the Outback, “especially if there is not a Jew or a black for a hundred miles around.” Rather cynically, the psychiatrist concludes that “a doctor’s first duty to his patient is to help him find breathing room and so keep him from going crazy. If P.T. can’t stand blacks and Bilderbergers, my experience is that there is not time enough to get him over it even if I could.”

♦♦♦

How might Walker Percy, if he were living today, update Love in the Ruins? I believe he would warn the angels of the left against flying above our finite estate, lest they abstract us from the concrete circumstances of our lives. How, he might ask, do such goods as diversity and inclusion threaten to produce an aerial existence that takes flight from the traditions and convictions that root us in time and place? How do they threaten to impose on us an egalitarian and relativist tyranny, flattening the hierarchies and dichotomies necessary for a well-ordered polis? How do well-intended social justice warriors assume their seraphic purity and unfallenness—when they tear down monuments honoring those who served nobly, albeit in defense of impure causes? How does their angelism seek to deny the insuperable tragedies of life, those incurable conditions that are often worsened in the attempt to correct them? What might they learn from Freud, who saw that unhappiness is endemic to human existence? Or from Kierkegaard’s view that anxiety embraced in the right way is the path to peace? Or from Scripture, that man is born to trouble as the sparks fly upward, and that patient forbearance is one of the highest virtues?

Percy would be no less alarmed, I believe, by the ways in which the bestialism of the right would plunge us fatally beneath our self-transcendent character. A brutish vision that does not rise above the world of getting and spending, as Wordsworth called it, lays waste to our powers of spiritual liberty by enslaving us to comfort and convenience. Why, Percy might ask, do bestial folks on the right define freedom as the acquisition of wealth and power so as to control and dominate others? How do they trample the little people of the earth—the poor and the hungry, the lonely and abandoned—in order to make big money for the sake of big pleasures? How are they turning us into swine with snouts buried in the trough of animal desire? Why do they seem to give not a fig for righting the historic wrongs accruing from the nation’s unjust racial and economic regimes? How does a Cartesian separation of their souls from their bodies account, at least in part, for the election of a self-confessed “pussy-grabbing” president?

Thomas More becomes impatient with such questions, if only because he is himself afflicted with both forms of our Cartesian sickness. On the one hand, he is a self-pleasuring bestial creature; he seeks sexual favors not from one but from the three women whom he has sequestered in the ruined Howard Johnson’s motel whence he has fled from the physical and political apocalypse he fears will soon be unleashed. More is also addicted to gin fizzes, even though their egg content triggers hives, sending him into anaphylactic shock and endangering his life. At the same time, More is angelically bewitched by the encephalographic machine he has invented. He calls it his lapsometer. He takes its name from the Latin lapsus, or fall, for it allegedly can detect the extent to which his patients have fallen away from an invisible dividing line, causing them to become either airily angelic or brutally bestial. More refuses the moral and religious therapies that require the long haul of history for their efficacy. Instead, he is filled with a proud Faustian desire to cure no less than diagnose. And so he seeks to make his machine omnicompetent—aiming to stimulate certain control centers of the brain so as to heal the riven psychic state of his patients. He would become a technocrat of the broken human soul, welding it together once again.

One of the novel’s largest ironies is that More remains a physician who, even if he could heal others, cannot heal himself. Of all men in Paradise Estates, he is perhaps most miserable. Desperately torn between his own angelism and bestialism, More slashes his wrists on Christmas Eve. He turns what should be the world’s happiest hour of birth into his own sad hour of attempted death. Wondrously, More recovers from his failed suicide. Lying in a hospital bed, lusting after his buxom nurse, he discerns the real answer to our cultural death knell. He does so by pondering Blaise Pascal’s maxim that we humans are ne ange, ne bête, neither angels nor beasts:

Later… I prayed, arms stretched out … tears streaming down my face. Dear God, I can see it now, why can’t I see it at other times, that it is you I love in the beauty of the world and in all the lovely girls and dear good friends, and it is pilgrims we are, wayfarers on a journey, and not pigs, nor angels. Why can I not be merry and loving like my ancestor, a gentle pure-hearted knight for our Lady and our blessed Lord and Savior? Pray for me, Sir Thomas More.

To know the good is not necessarily to do it, as St. Augustine learned in a Milan garden in August of 386. More wants to become a pilgrim and wayfarer without a price, to be delivered without undergoing drastic transformation. In his split Cartesian condition, he prefers to remain a fornicating alcoholic and a salvation-peddling scientist than to have his loves radically reordered. More makes this darkest of discoveries when he contemplates his reasons for not wanting his fatally ill daughter to seek the miraculously curative waters at Lourdes:

I don’t know Samantha’s reasons [for not wanting the baths], but I was afraid she might be cured. What then? Suppose you ask God for a miracle and God says yes, very well. How do you live the rest of your life?

Samantha, forgive me. I am sorry you suffered and died, my heart broke, but there have been times when I was not above enjoying it.

Is it possible to live without feasting on death?

For Walker Percy, this is the chief question of our time: How might we cease gorging ourselves on the twin forms of death that threaten to dehumanize us, turning us into maleficent angels and beasts? What would it mean to be transformed into wayfarers seeking the welfare of the earthly city, while also living as pilgrims bound for another City, one not made with hands but eternal in the heavens?

The novel’s barely glimpsed hope is figured in another dark scene, an episode concerning Father Rinaldo Smith, the pastor of a small remnant parish of faithful Roman Catholics. When Fr. Smith stands one Sunday to deliver the homily before serving the Mass, he falls stone silent, unable to utter a word. His parishioners rush him to the sacristy, assuming that he has suffered a sudden seizure, perhaps even a collapse of nerves. Later, Fr. Smith gropes to explain why his tongue froze in the pulpit. He has not suffered aphasia, as his attending doctors suspect, the brain malfunction that causes speechlessness. Smith makes the strange claim, instead, that he couldn’t speak because “they’re jamming the air waves.” Nor was it electronic gremlins that had hacked into the speaker system. Fr. Smith insists that he was made mute by the “principalities and powers.” He’s referring, of course, to the demonic forces that, according to St. Paul, we always struggle against. Precisely because devils are deprived of substantial being, they rule the world almost wholly undetected. It was these satanic powers that had silenced Fr. Smith. “They’ve won and we’ve lost,” he laments. The priest concludes with a haunting confession that Percy the prophet requires his readers to confront: “I am surrounded by the corpses of souls,” Smith says. “We live in a city of the dead.” So late is the hour, so dreadful the calamity, that Percy identifies our massive cultural death as deriving not from winged creatures with horns and spears and tails, but from ordinary human beings whose souls and bodies have been so riven as to make us sick unto death. The subtle principalities of the angelic left, like the gross powers of the bestial right, have made us dead to ourselves, dead to others, dead to God.

Tom More can find no exit from such a hellish culture of death in either of the available ecclesial and political alternatives; they are but mirror images of each other. His only hope lies in his early confession that, like the father whose epileptic son had been healed by Jesus, he remains a believer even in his unbelief. Fr. Rinaldo Smith’s faithful renegade flock of remnant Catholics are the only vital believers to be found. And so, in a redemptively reverse manner, More finds himself backing into the Kingdom. When Fr. Smith seeks to shrive him on Christmas Eve five years after the novel’s main action closes, More confesses his sins in a single sentence: “I do not recall the number of occasions, Father, but I accuse myself of drunkenness, lusts, envies, fornication, delight in the misfortune of others, and loving myself better than God and other men.” Though More can make his confessio oris, he is powerless to exhibit any contritio cordis. He has no sorrow of heart. He is ashamed not of his sins but of not being sorry for committing them. Father Smith knows that, in the mathematics of the Gospel, such a double negative constitutes a miraculous if minuscule positive.

Accordingly, the humble priest assigns More an appropriate satisfactio operis: this barely contrite psychiatrist must make public penance by dousing his hair with ashes and wearing a sweater made of burlap. And so More attends midnight Mass for the first time in many years, once again eating Christ (as he says) and thus having life restored to him. In the meantime, he has married his nurse Ellen Oglethorpe, the only one of his sequestered women whom he had never bedded. They, in turn, have enshrined their hope for the future by naming their young son Thomas More, Jr. Yet the elder More is no instant saint, as he still lusts after a neighbor’s wife across the backyard fence, still swigs from his hidden bottles of bourbon, still hopes that he might make his lapsometer work. Even so, he has begun his pilgrimage away from the angelism and bestialism of his former life, making his way toward la vita nova, as Dante called it.

Barbecuing in my sackcloth.

The turkey is smoking well….

The night is clear and cold. There is no moon. The light of the transmitter lies hard by Jupiter, ruby and diamond in the plush velvet sky. Ellen is in the kitchen fixing stuffing and sweet potatoes. Somewhere in the swamp a screech owl cries.

I’m dancing around to keep warm, hands in pockets. It is Christmas Day and the Lord is here, a holy night and surely that is all one needs.

On the other hand, I want a drink. Fetching the Early Times from a clump of palmetto, I take six drinks in six minutes. Now I am dancing and singing old Sinatra songs and the Salve Regina, cutting the fool like David before the ark or like Walter Huston doing a jig when he struck it rich in the Sierra Madre.

♦♦♦

As Wordsworth said of Milton, so might we plead: “Percy, wert thou living at this hour!” Though it’s 28 years past his death and 47 since publication of Love in the Ruins, he might call Christians to a similar kind of hope. Though he would be witty rather than solemn, I believe he would summon his fellow believers, not to a culture war against the twin evils of the left and the right, but rather to a drastic renewal of our badly fractured churches. Father Rinaldo Smith’s tiny flock might find its successors in small gatherings of Christians from across the denominations in order that the Gospel might survive amidst the Dark Ages that have already begun. Aboard the church’s rickety ark riding out the storm, these remnant Christians would create communities of refuge for those who desire “a better country” (Heb. 11:14) than our bestial and angelic Cities of the Plain.

For nearly a half century, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI has been making a similar summons. He has confessed that we Christians are likely to remain a permanent minority from here on in—barring, of course, a miraculous outpouring of the Holy Spirit in a phoenix-like rebirth from our moral and spiritual ashes. We Christians will never be in charge of things again, the future pope acknowledged. We seem to be back where we began—as a minority faith in an overwhelmingly pagan world. Hence these startling words from a 1969 radio address entitled “What Will the Church Be Like in 2000?”:

She will become small and will have to start afresh more or less from the beginning. She will no longer be able to inhabit many of the edifices she built in prosperity. As the number of her adherents diminishes, so will she lose many of her social privileges. In contrast to an earlier age, she will be seen much more as a voluntary society, entered only by free decision. As a small society, she will make much bigger demands on the initiative of her individual members…. The Church will be a more spiritual Church, not presuming upon a political mandate, flirting as little with the Left as with the Right. It will be hard going for the Church, for the process of crystallization and clarification will cost her much valuable energy. It will make her poor and cause her to become the Church of the meek…. But when the trial [of] this sifting is past, a great power will flow from a more spiritualized and simplified Church.

Yet it’s not as if two millennia of Christian existence have made no difference. In a 1997 interview with Peter Seewald, a German atheist reporter, Cardinal Ratzinger declared that we have been given two unparalleled gifts wherewith to build such enclaves of radical Christian excellence: (1) the inexhaustible fund of Christian thought and art, and (2) the unsurpassable witness of our saints and martyrs. On a sure prophetic and sacramental foundation, such mustard seed churches will “live in an intensive struggle against evil.” They will seek to keep “what is essential to man from being destroyed.” They will bring “good into the world,” prophesied the future pope, and thus “let God in.”

The God of the Gospel is no bully. He will not force his way in. He knocks patiently at the door. As in the case of Dr. Thomas More, the Lord often makes backdoor entrances, through redemptive defeats rather than pyrrhic victories. “Despair,” the wizard Gandalf declares in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, “is only for those who see the end beyond all doubt.” So does Walker Percy summon his present-day readers to a deeply ironic but no less bracing hope, by way of his funny, frighteningly prophetic novel of 1971—to make both life and love in the ruins.

Ralph C. Wood is University Professor of Theology and Literature at Baylor. He holds a B.A. and M.A. from East Texas State College (now Texas A&M University-Commerce) as well as an A.M. and Ph.D. from the University of Chicago.

Comments