Why Do We Still Have War Booty From The Philippines?

Many Americans view their country as a national Virgin Mary, blameless and without sin. When Washington intervenes abroad, even when visiting death and destruction on foreign peoples, it is an act of righteousness on behalf of the Lord.

Yet for those on the other end of U.S. bullets and bombs—think Yemeni schoolchildren killed by Saudi aircraft armed, refueled, and guided by Washington—America looks like anything but an avenging angel. The tragic reality is that myopic policymakers are turning patriotic military personnel into war criminals for venal ends.

Yemen is not the first such shameful moment. Many conflicts in our history were foolish, counterproductive, and shortsighted. Several were justified by fraud and lies. Yet most retained at least a patina of moral justification, no matter how infirm in practice. For instance, while Eastern financial interests pushed for war to protect their abundant loans to Great Britain, President Woodrow Wilson probably did believe that preserving the right of Americans to travel unmolested on British ships—armed reserve naval cruisers carrying munitions through a war zone—constituted a righteous cause.

No such moral veneer can be applied to the Philippine-American War, waged more than a century ago. Indeed, most Americans probably are not even aware of that conflict. They are taught that Teddy Roosevelt and a few other guys, some of whom were on ships, defeated the murderous Spanish Empire and freed Cubans and Filipinos from horrid oppression. What came next is barely mentioned in most civics texts.

It turns out the Filipinos were already fighting to liberate themselves, and led by Emilio Aguinaldo, they undertook an armed insurgency against their Spanish overlords. Still, President William McKinley was focused on Cuba, pointing to atrocities by Madrid’s forces to justify America’s war against Spain—which, of course, in no way threatened the U.S. Madrid’s policies were dreadful, but no worse than Washington’s treatment of Native Americans. Nevertheless, American sanctimony was on full display.

Even if we’d had legitimate cause to “liberate” Cuba, the Philippines was separate, largely ignored by William Randolph Hearst and other “yellow journalists” who stirred up war fever. But for many American imperialists, the Philippines was the real objective. It offered a base for Pacific naval operations and could act as a station on the way to accessing the presumably limitless markets of China.

So Washington sent the navy under Commodore George Dewey to the island archipelago. Dewey brought Aguinaldo from Hong Kong, where he had been in exile, to the Philippines, to undermine the Spanish authorities, and his forces quickly gained control of several provinces and helped invest Manila. However, the U.S. refused to allow Aguinaldo to enter the capital after its capture and expected the Filipino rebels to obey their new conquerors.

Having ousted one colonial overlord, the Filipinos were not inclined to accept another, and fighting soon broke out, triggering the second round in the Filipino war of independence. The result has been called the Philippine-American War, Philippine Insurrection, Tagalog Insurgency, and Philippine War. It was a war of liberation against foreign imperialism, only this time with Americans in the role of oppressors.

Indeed, U.S. forces eventually adopted the brutal Spanish practices used against insurgents in Cuba, which had spurred America’s original declaration of war. American officials and officers actually pointed to the virtual extermination of the Native Americans as a possible model. Estimates of the number of deaths start at around 250,000 and race up towards a million (comparable to the casualty estimates for Washington’s recent Iraq misadventure).

The conflict lasted more than three years. Aguinaldo was eventually captured and the struggle officially declared over on July 2, 1902. However, sporadic battles continued, especially on the southern Islamic islands, where fighting still occurs today. Washington eventually relaxed its control and freed its colony. Although the Philippines today is independent, it staggers along as a semi-failed state. Corrupt authoritarianism was the highlight of the Marcos’ lengthy rule. Corrupt incompetence has been the measure since. Today’s president, Rodrigo Duterte, is authoritarian and murderous, at least towards drug sellers and users, and a fan of China.

What is done is done, of course. Those needlessly killed by Washington’s brutally aggressive strategy cannot be raised again, at least in advance of the Second Coming. However, that doesn’t mean no recompense is possible. An acknowledgement by current policymakers that bloody imperialism has no place in American foreign policy would be welcome, as well as a determination not to slaughter other peoples because doing so might serve some vague international objective of at most modest value.

The end of the Cold War offered Washington an opportunity to refashion its approach to the world and adopt what President George W. Bush once called a “humble foreign policy.” Yet becoming a unipower only made America aggressive in different ways. Indeed, as Washington’s malign involvement in such wars as Iraq and Yemen demonstrates, the U.S. became more dangerous, not less.

However, there are other small steps that Washington could take to make amends for its prior aggressions. For instance, the Pentagon is preparing to make an important act of symbolic repentance for its depredations during the Philippine-American War. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis has informed Congress that the department intends to return what are known as the Bells of Balangiga, war booty seized more than a century ago.

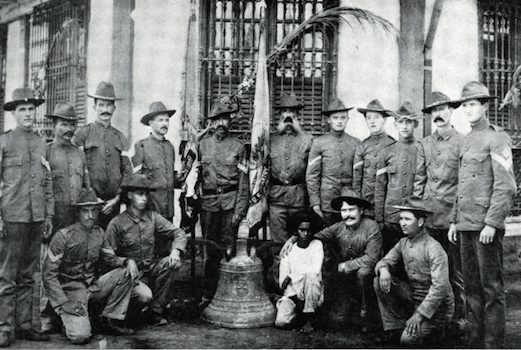

One of the many fights in the Philippines occurred in the village of Balangiga on September 28, 1901, when Filipino insurgents surprised U.S. military forces at breakfast, killing 48 of them. It was but a modest victory over those who had inflicted so much harm and hardship on the Philippine people—and the triumph was only temporary.

Those representing “the land of the free and the home of the brave” returned to exact brutal reprisals. General Jacob Smith instructed his soldiers to turn the land into a “howling wilderness” and “kill everyone over the age of ten.” Thousands of Filipinos died and Balangiga was burned down. Among the buildings destroyed was the church. From the ruins the Americans took away three bells, one of which was used to signal the Filipino attack.

The 9th Infantry Regiment kept one bell, which is displayed at the divisional museum at Camp Red Cloud in South Korea. The 11th Infantry Regiment took the other two bells, and they are lodged at Warren Air Force Base (originally Fort Russell) at Cheyenne, Wyoming. Beginning in the 1990s, the Philippine government began asking for the bells’ return. A decade later, the Catholic Church, which lost a sanctuary as well as bells, joined in the request. In fact, Balangiga’s Church of St. Lawrence the Martyr maintains an empty belfry, ready to receive the bells. Earlier this decade, the town also asked for the bells back.

Last year, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte requested that Washington turn over the bells. He made his case powerfully: “Those bells are reminders of the gallantry and heroism of our forebears who resisted the American colonizers and sacrificed their lives in the process.” He added that the bells “are part of our national heritage. Return them to us. It pains us.”

However, Americans remain attached to their war trophies. Past requests were ignored or denied. After Duterte’s request, legislators from Wyoming and two congressmen from other states objected, citing his encouragement of extrajudicial killings. But Duterte’s atrocities don’t mitigate Washington’s need to make peace with the memory of murdered Filipinos.

The bells are not, say, uniforms, letters, or guns. Rather, they are all that remains of an entire community whose buildings were destroyed and residents killed by American military personnel. This was done in a larger war undertaken for the immoral, unjust objective of enforcing Washington’s rule upon a foreign people seeking the same thing as American colonists did a century before—independence and self-rule.

While today’s veterans and the sacrifices they made deserve respect, we must not rewrite history to sanctify the wars in which they fought. This case should be easy, since acknowledging the truth of America’s tragic, brutal intervention would embarrass no one still living. All those who served in the Philippine-American War, including those who served badly, are long dead.

If America aspires to be great, it must confront its history in order to learn from it rather than repeat it. The Bells of Balangiga should go home.

Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. A former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.

Comments