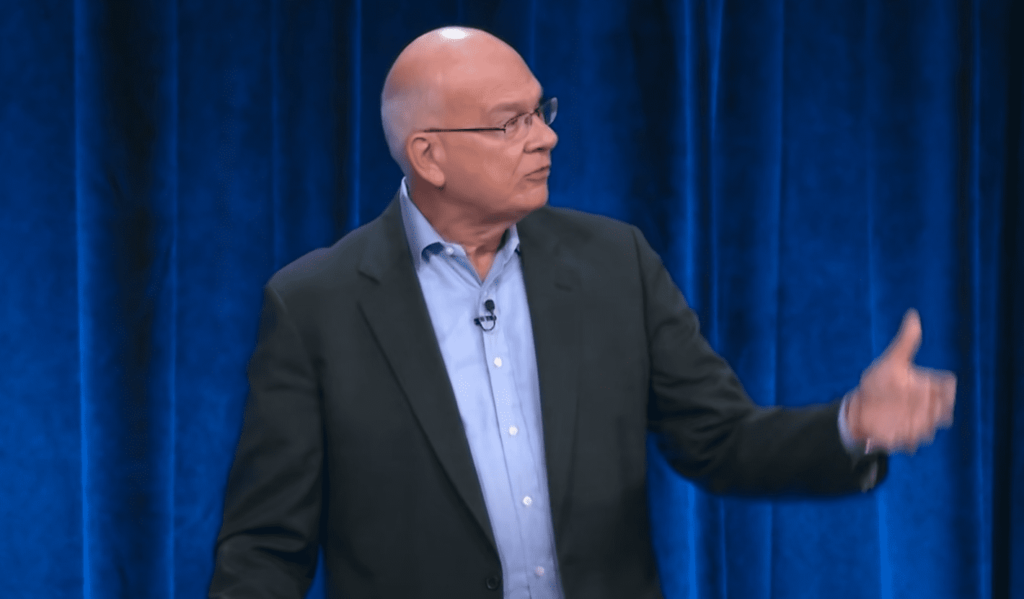

Tim Keller & Myxomatosis Christians

So, David French. You might have seen his vociferous defense of the renowned Presbyterian pastor Tim Keller. It highlights David’s strengths as a polemicist, and the admirable loyalty of his character … but also his weakness as a reader of the signs of the times. Caveat: David is a friend, and though I disagree with him on a lot of things, I am not joining the Hate David French crowd. I believe David is always worth listening to, even when he’s wrong. And even when he’s wrong, I prefer listening to him make his case with respect and even kindliness than I do people who are on my side ideologically trying to sneer their opponents into submission.

Nevertheless, David is quite wrong here. Let’s get into it.

What prompted French’s essay? This piece by James Wood, an editor at First Things, talking about how much he admires Tim Keller, but how he believes Keller’s time has passed. Excerpts:

Keller’s winsome approach led him to great success as an evangelist. But he also, maybe subconsciously, thinks about politics through the lens of evangelism, in the sense of making sure that political judgments do not prevent people in today’s world from coming to Christ. His approach to evangelism informs his political writings, and his views on how Christians should engage politics. For years, Keller’s approach informed my views of both evangelism and politics. When I became a Christian in college, both my campus ministry and my church were heavily influenced by Keller’s “winsome,” missional, “gospel-centered” views. I liked Keller’s approach to engaging the culture—his message that, though the gospel is unavoidably offensive, we must work hard to make sure people are offended by the gospel itself rather than our personal, cultural, and political derivations. We must, Keller convinced me, constantly explain how Christianity is not tied to any particular culture or political party, instead showing how the gospel critiques all sides. He has famously emphasized that Christianity is “neither left nor right,” instead promoting a “third way” approach that attempts to avoid tribal partisanship and the toxic culture wars in hopes that more people will give the gospel a fair hearing. If we are to “do politics,” it should be in apologetic mode.

But times changed. More:

At that point, I began to observe that our politics and culture had changed. I began to feel differently about our surrounding secular culture, and noticed that its attitude toward Christianity was not what it once had been. Aaron Renn’s account represents well my thinking and the thinking of many: There was a “neutral world” roughly between 1994–2014 in which traditional Christianity was neither broadly supported nor opposed by the surrounding culture, but rather was viewed as an eccentric lifestyle option among many. However, that time is over. Now we live in the “negative world,” in which, according to Renn, Christian morality is expressly repudiated and traditional Christian views are perceived as undermining the social good. As I observed the attitude of our surrounding culture change, I was no longer so confident that the evangelistic framework I had gleaned from Keller would provide sufficient guidance for the cultural and political moment. A lot of former fanboys like me are coming to similar conclusions. The evangelistic desire to minimize offense to gain a hearing for the gospel can obscure what our political moment requires.

Keller’s apologetic model for politics was perfectly suited for the “neutral world.” But the “negative world” is a different place. Tough choices are increasingly before us, offense is unavoidable, and sides will need to be taken on very important issues.

You do need to read Aaron Renn’s account if you haven’t already. It’s important to understand why Wood takes the view that he does.

Wood writes in sorrow, and with clear respect and affection for Keller. French responded angrily, though. Here’s how French headlined his essay:

Excerpts from his rebuttal:

There are so many things to say in response to this argument, but let’s begin with the premise that we’ve transitioned from a “neutral world” to a “negative world.” As someone who attended law school in the early 1990s and lived in deep blue America for most of this alleged “neutral” period, the premise seems flawed. The world didn’t feel “neutral” to me when I was shouted down in class, or when I was told by classmates to “die” for my pro-life views.

Nor was the world “neutral” for Tim. Last night he tweeted about his experience launching Redeemer church in New York:

And if you want empirical evidence that New York City wasn’t “neutral” before 2014, there was almost 20 years of litigation over the city’s discriminatory policy denying the use of empty public school facilities for worship services. The policy existed until it was finally reversed by Mayor Bill de Blasio in 2015.

Even growing up in the rural south, I wasn’t surrounded by devout Christianity, but instead by drugs, alcohol, and a level of sexual promiscuity far beyond what we see among young people today. Where was this idealized past? There may have been less “woke capital,” but there was more crime, more divorce, and much, much more abortion.

This misses the point about Renn’s “negative world” distinction (again: read Renn’s piece!). Here is a capsule of Renn’s belief:

In recent decades, the church has passed through three eras or worlds in terms of how American society perceives and relates to the church. These are the positive, neutral, and negative worlds, with the names referring to the way society views Christianity.

Positive World (Pre-1994). Christianity was viewed positively by society and Christian morality was still normative. To be seen as a religious person and one who exemplifies traditional Christian norms was a social positive. Christianity was a status enhancer. In some cases, failure to embrace Christian norms hurt you.

Neutral World (1994-2014). Christianity is seen as a socially neutral attribute. It no longer had dominant status in society, but to be seen as a religious person was not a knock either. It was more like a personal affectation or hobby. Christian moral norms retained residual force.

Negative World (2014-). In this world, being a Christian is now a social negative, especially in high status positions. Christianity in many ways is seen as undermining the social good. Christian morality is expressly repudiated.

Renn is not claiming — it would be absurd to claim — that there was no hatred of Christianity in Positive World. Nor is he claiming that Christianity is everywhere hated. He’s generalizing about American culture — and he’s absolutely right about Negative World. I have far too many conversations with people who are senior within American institutions, both public and private, who tell me in detail what’s happening in their professional circles. I have described America as a “post-Christian nation,” meaning not that there are no Christians, but that Christianity is no longer the story that most Americans regard as explaining who we are. You might think that’s great, you might think that’s terrible, but it’s simply true.

Christians who count themselves as progressive on woke issues — LGBT, race — don’t experience Negative World as intensely, if at all. And, if you have been a vocal Never Trumper, as David French has, you gain a lot of points in Negative World with the people who run it.

Similarly, it’s a mistake to claim that because some social indicators (crime, abortion) are better today than they were when David French and I were growing up in Positive World, that this was a golden era for which Christians like Aaron Renn, James Wood, and me long. The point we make is not about the supposed Edenic qualities of the past. We have always had sin and brokenness in this country, and always will. The world is always in need of conversion, and the church is always in need of reform and repentance. The point was that in Positive World, Christianity and its ideals were held generally by society as something to be aspired to. If they weren’t, the Civil Rights Movement — led by black pastors! — would not have been possible, at least not in the form it took.

Today, in Negative World, not every workspace or social gathering site is uniformly negative, any more than in Positive World, Christians experienced welcome in, say, Ivy League law schools. The claim is a general one. I recall meeting a Portland (Oregon) megachurch pastor backstage at a Christian event two or three years ago, and him telling me that when The Benedict Option came out in 2017, he and all his friends thought Dreher was an alarmist. No more, he said. The pastor told me that the church did not change, but everything around them did. They went from being seen in Portland as sweet, essentially harmless eccentrics to being a fifth column for fascism. He told me that they are now trying to figure out how to live the Benedict Option — and he said that what is happening in Portland is going to come to most of America eventually.

I can tell you from abundant personal experience that very many conservative, or conservative-ish, pastors and lay leaders are afraid to draw the obvious conclusions from what they see around us. I just returned from spending a couple of days at a great conference of the Anglican Church of North America’s Diocese of the Living Word. Such brave and faithful and kind people there, and such inspiring pastors. But in several conversations, I heard confirmation of what I have heard from many others within church circles, and seen myself: far, far too many conservative pastors and lay leaders are desperately clinging to the false hope that we are still living in either Positive World or Neutral World, and that if they just keep calm and carry on preaching and pastoring as if all was basically well, everything’s going to calm down.

It’s not. It’s accelerating, and thinking that it’s not is pure cope. If you have the time, watch or listen to this recent podcast discussion with Jonathan Pageau and Paul Kingsnorth, which touches on these themes. They talk mostly about the totalitarian uses of today’s technology, and discuss at times how this is going to be used against all dissidents, including Christians. Paul talks about the relevance of the Benedict Option, and says we might even need to go further, to the “Anthony Option” — meaning, heading to the desert, like St. Anthony the Great, the founder of monasticism.

Anyway, back to French:

It’s important to be clear-eyed about the past because false narratives can present Christians with powerful temptations. The doom narrative is a poor fit for an Evangelical church that is among the most wealthy and powerful Christian communities (and among the most wealthy and powerful political movements) in the entire history of the world.

Yet even if the desperate times narrative were true, the desperate measures rationalization suffers from profound moral defects. The biblical call to Christians to love your enemies, to bless those who curse you, and to exhibit the fruit of the spirit—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control—does not represent a set of tactics to be abandoned when times are tough but rather a set of eternal moral principles to be applied even in the face of extreme adversity.

Moreover, Christ and the apostles issued their commands to Christians at a time when Christians faced the very definition of a “negative world.” We face tweetings. They faced beatings.

Wait a minute. French is certainly correct that we Christians have to love our enemies, and all the rest. And he is right that far too many besieged Christians today put that aside (a temptation of mine, I confess). But loving one’s enemies does not mean that one should close one’s eyes to the fact that they are enemies, and wish to do us serious harm. The wealth and power of American Evangelicals is something true for this time and this place. It won’t always be true. I spoke to someone at the ACNA conference who told me about a Cuban immigrant he met not long ago. She told him, “I come from your future.” He asked her what she meant by that. She told him that she can feel “in my bones” the coalescing in the United States of the totalitarianism she fled in her homeland.

Over and over and over, people who fled to America to escape Communist totalitarianism say the same thing. This is why I wrote Live Not By Lies: to relay their message, and to encourage the churches in the West both to resist while we can, and to prepare for when and if that resistance fails. The position that American Evangelicals have today will not last. Christianity is in steep decline in America, especially among the young. This, combined with the rising persecutorial sense among the woke left, who run American institutions, means that the road ahead for Christians who have not been tamed by compromise with the world will be a very, very hard one.

If you haven’t read, or have forgotten, this much-discussed 2015 discussion I had with “Prof. Kingsfield,” the name I gave to a closeted Christian law professor at a top law school, you should. Remember, this was seven years ago — and a month before the Obergefell decision. Excerpt:

What prompted his reaching out to me? “I’m very worried,” he said, of events of the last week [the beatback of the Indiana RFRA law under immense pressure from woke capitalism — RD]. “The constituency for religious liberty just isn’t there anymore.”

Like me, what unnerved Prof. Kingsfield is not so much the details of the Indiana law, but the way the overculture treated the law. “When a perfectly decent, pro-gay marriage religious liberty scholar like Doug Laycock, who is one of the best in the country — when what he says is distorted, you know how crazy it is.”

“Alasdair Macintyre is right,” he said. “It’s like a nuclear bomb went off, but in slow motion.” What he meant by this is that our culture has lost the ability to reason together, because too many of us want and believe radically incompatible things.

But only one side has the power. When I asked Kingsfield what most people outside elite legal and academic circles don’t understand about the way elites think, he said “there’s this radical incomprehension of religion.”

“They think religion is all about being happy-clappy and nice, or should be, so they don’t see any legitimate grounds for the clash,” he said. “They make so many errors, but they don’t want to listen.”

To elites in his circles, Kingsfield continued, “at best religion is something consenting adult should do behind closed doors. They don’t really understand that there’s a link between Sister Helen Prejean’s faith and the work she does on the death penalty. There’s a lot of looking down on flyover country, one middle America.

“The sad thing,” he said, “is that the old ways of aspiring to truth, seeing all knowledge as part of learning about the nature of reality, they don’t hold. It’s all about power. They’ve got cultural power, and think they should use it for good, but their idea of good is not anchored in anything. They’ve got a lot of power in courts and in politics and in education. Their job is to challenge people to think critically, but thinking critically means thinking like them. They really do think that they know so much more than anybody did before, and there is no point in listening to anybody else, because they have all the answers, and believe that they are good.”

On the conservative side, said Kingsfield, Republican politicians are abysmal at making a public case for why religious liberty is fundamental to American life.

“The fact that Mike Pence can’t articulate it, and Asa Hutchinson doesn’t care and can’t articulate it, is shocking,” Kingsfield said. “Huckabee gets it and Santorum gets it, but they’re marginal figures. Why can’t Republicans articulate this? We don’t have anybody who gets it and who can unite us. Barring that, the craven business community will drag the Republican Party along wherever the culture is leading, and lawyers, academics, and media will cheer because they can’t imagine that they might be wrong about any of it.”

Kingsfield said that the core of the controversy, both legally and culturally, is the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey (1992), specifically the (in)famous line, authored by Justice Kennedy, that at the core of liberty is “the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” As many have pointed out — and as Macintyre well understood — this “sweet mystery of life” principle (as Justice Scalia scornfully characterized it) kicks the supporting struts out from under the rule of law, and makes it impossible to resolve rival moral visions except by imposition of power.

“Autonomous self-definition is at the root of all this,” Prof. Kingsfield said. We are now at the point, he said, at which it is legitimate to ask if sexual autonomy is more important than the First Amendment.

The implications of the past week for small-o orthodox Christians — that is, those who hold to traditional Christian teaching on homosexuality and the nature of marriage — are broad. There is the legal dimension, and there is a cultural dimension, which Kingsfield sees (rightly, I think) as far more important.

Once more, back to David French. I agree with him that far too many Christians in our country are obsessed with politics, and allow their political convictions to shape their religious views, rather than the other way around. That said, I have had to come to the realization that my own pious disdain for politics (“a pox on both your houses”) is no longer tenable. The assault on children by the pro-trans ideologues — including the one who lives at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue — red-pilled me on that. I continue to believe that absurd Christian displays like the Jericho March, which I criticized here, do far more harm than good, both to the cause of Christianity in America, and to the cause of building resistance to the Machine/Cathedral. That said, I also believe that the “winsome” approach advocated by Tim Keller and David French is a different kind of poison pill. French writes:

We live in an age of negative polarization, when the cardinal characteristic of partisanship is personal animosity. In these circumstances, a Christian community characterized by the fruit of the spirit should be a burst of cultural light, a counterculture that utterly contradicts the fury of the times. Instead, Christian voices ask that we yield to that fury, and that a “negative world” is now no place for the “winsome, missional, and gospel-centered approach.”

But this isn’t an evolution from Tim Keller, it’s a devolution, and it’s one that’s enabling an enormous amount of Christian cruelty and Christian malice. Wood says “Keller was the right man for a moment,” but he also says, “it appears that moment has passed.” That’s fundamentally wrong. When fear and hatred dominates discourse, a commitment to justice and kindness and humility is precisely what the moment requires.

No, I stand with James Wood and Aaron Renn here: the moment really has passed. The moment for Christians to love our enemies and pray for them will never pass, this is true. But the idea that they will embrace us, or even tolerate us, if we just be sweet is no longer viable. I don’t advocate at all hating our enemies. Neither did Martin Luther King. But King also recognized that he and the movement he led really did have enemies, and that these enemies were willing to do violence to them. We non-conforming Christians are moving into the same world, very rapidly — except this time, the technological powers that our enemies have to use against us are without parallel in world history. As Kingsnorth and Pageau were talking, Justin Trudeau showed that the Canadian state is prepared to seize the bank accounts of dissenters and cut them off from participating in the economy. Kingsnorth, who was once on the activist Left, says he cannot figure out why his old comrades used to view the state and major corporations with deep suspicion and hostility … but now that those powerful entities have aimed their fire at the kind of people progressive activists hate, the Left is fine with it.

I don’t know a lot about Tim Keller, except by reputation. He seems to be a very fine man, and devout Christian. I couldn’t imagine saying a bad thing about him, but some of you Evangelicals who follow him more closely than I do might disagree. All I can say is that Winsome World Christians are failing to prepare themselves, their families, and (if pastors) their flocks for the world that exists today, and the world that is fast coming into being. Again, I am thinking of the pastor I argued with who believed that he didn’t need to speak about gender ideology to his parish (“I don’t want politics in my congregation”) because, as he explained, if he just keeps winsomely teaching Biblical principles, all will be well. I am certain that man believed he was taking a virtuous stand against fearmongers and alarmists like Dreher. I think it was cowardice.

We all need to be spending a lot more time reflecting not on the wisdom of bourgeois American pastors, and more time on the experiences of the persecuted churches abroad. This morning I’m thinking about the Christians of Syria. Do you know that nearly all of them support the Assad dictatorship? Do you think they do this because they love Bashar Assad, or love dictatorship? No, they do this because they know perfectly well that if Assad fell, even if democracy somehow came to Syria, they would all be killed by the Islamist majority. This is not a theory. They know. We are not anywhere close to that in America, obviously, and I hope and pray we don’t get there. But the principle is still in play. American Christians have to learn how to endure persecution without capitulating to apostasy or to hatred. And when it comes to thinking about political engagement, we need moral realism. Christians who think we are going to vote our way out of this crisis are beyond deluded, as I have been saying for years. But Christians who believe that voting doesn’t really matter are also deluded.

Winsomeness is not going to prepare the churches for what is fast coming to us. That is not a rationalization for embracing hatred! But it is a warning to individual believers and leaders, both ordained and lay, to read the signs of the times, and act. The Christians who have lived through this sort of thing before, and who are warning us today, have strong counsel for us in my book Live Not By Lies.

One of the most important things I learned in reporting this book is something that dissident Kamila Bendova, the wife of the late political prisoner Vaclav Benda, told me. She said that she and her husband, despite being very strong conservative Catholics, had no problem at all working closely with Vaclav Havel and his hippie dissident circles. Kamila told me that when you are facing the kind of dragon they had to fight, the rarest quality is courage. She said most Czech Christians kept their heads down and conformed to avoid trouble. Kamila and her husband had more in common with the brave atheist hippies who refused to live by lies, and who were willing to suffer for it.

And for us? Better to stand with a Bari Weiss, a Bret Weinstein, or a Peter Boghossian than with Christians who are trying really very, very hard to convince themselves that everything is basically okay, and that we should just keep on living like we always have, and all will be well. In a poetic sense, they suffer from a form of myxomatosis: the disease introduced by the British into rabbits to control the population. Philip Larkin wrote a poem, titled “Myxomatosis,” about them:

Caught in the center of a soundless field

While hot inexplicable hours go by

What trap is this? Where were its teeth concealed?

You seem to ask.

I make a sharp reply,

Then clean my stick. I’m glad I can’t explain

Just in what jaws you were to suppurate:

You may have thought things would come right again

If you could only keep quite still and wait.

Don’t be a follower of St. Myxomatosis, is what I am telling you Christians. This doesn’t make Tim Keller a bad man — indeed, based on everything I’ve heard and read about him, he seems like an exceptionally good man, and certainly a man who has done vastly more for the Kingdom of God than I have done. But it does make him yesterday’s man, fighting yesterday’s war.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.