The War Against Austerity

From the president to the secretary of defense, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and every Republican and Democrat at the top of Congress’ defense committees, they all agree: “austerity” at the Pentagon must end. American forces are not getting enough money for training; weapons are short of maintenance; our forces are shrinking, and the defense industrial base is struggling. The Islamic State’s success in the Middle East makes the argument for a bigger Pentagon budget compelling at the strategic level.

One au courant pundit articulated this conventional wisdom saying “the [budget] cuts intensify a growing global concern that America is in decline.”

Joining the crowd, President Obama said the “Draconian” cuts in the Pentagon budget must be reversed.

The fix is in. The Pentagon is to be rescued from the spending cuts imposed by the three-year-old Budget Control Act of 2011 and its sequestration process. The rationale for reduction has been overtaken by world events, precipitous declines in military readiness, contraction of our forces and badly needed hardware modernization.

These arguments collapse under scrutiny.

What Austerity?

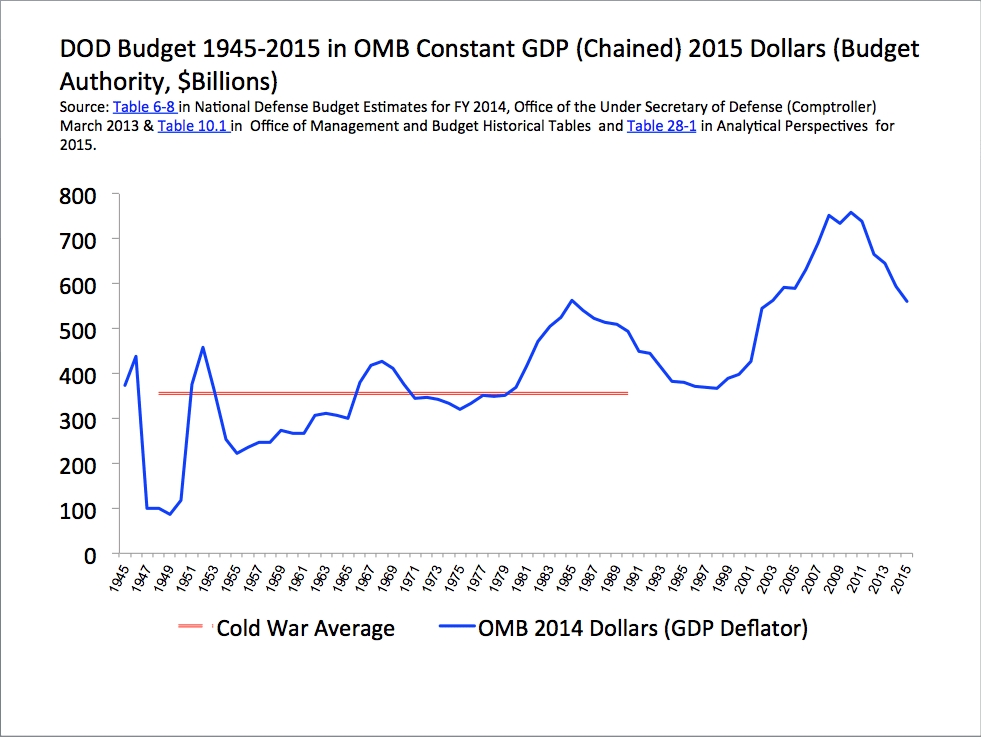

The graph below shows Pentagon spending since the end of World War II. The dollars have been adjusted for inflation using the Office of Management and Budget’s most widely accepted measure of it.

First, note in the upper right hand corner of the graph there has, indeed, been a real decline in Department of Defense (DOD) spending since 2010. The Budget Control Act has reduced “base” (non-war) Pentagon spending from $540 billion in 2010 to $496 billion today, and the American withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan have meant reductions in war spending from $160 billion in 2010 to $59 billion in Obama’s 2015 budget request.

However, look also at where current DOD spending is in 2015 compared to post-World War II history. The reductions since 2010 have left the Pentagon’s budget at a level that matches the Cold War peak during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. The current level exceeds any year during the Cold War—a time when America faced hundreds of divisions of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact in Europe, a dogmatically communist China and the international machinations of both in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Central and South America.

Next, compare current spending ($560 billion) to the horizontal dotted line in the graph, which represents average annual spending during the Cold War: $355 billion (also in inflation-adjusted dollars). The Pentagon spends today more than $200 billion more than it did during the Cold War, when the threat was the huge Soviet defense machine, which was far, far larger than anyone’s count of fighters for the Islamic State or today’s impoverished Russian military.

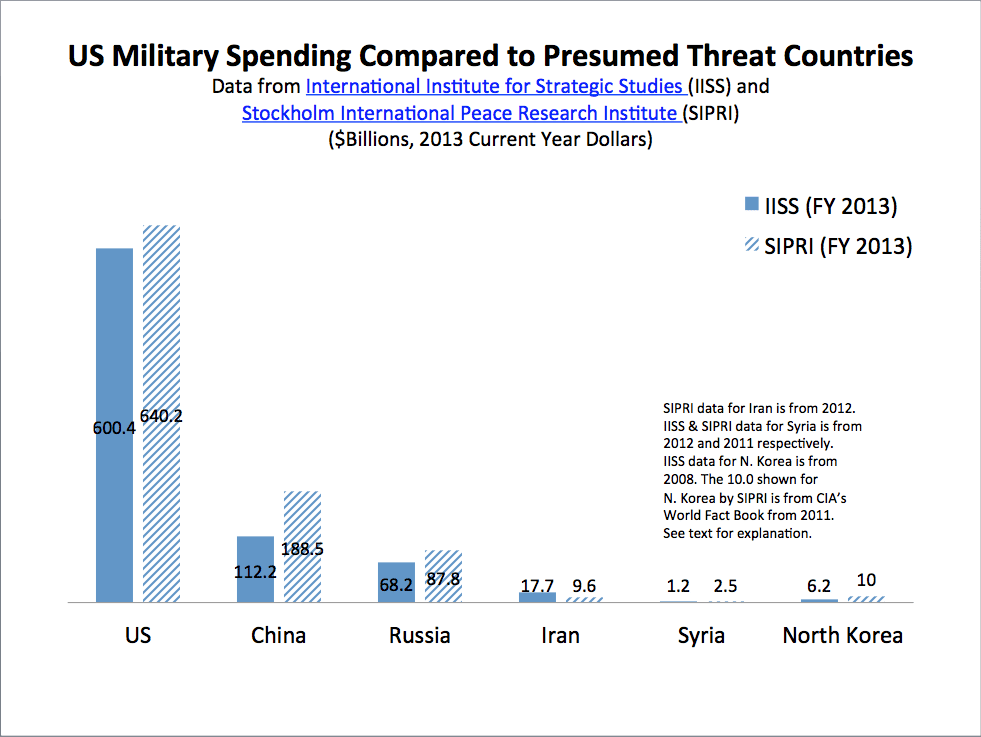

More contemporary data broadens the context. The next graph, below, compares the Pentagon’s current budget to military spending in China, Russia, Iran, Syria, and North Korea.

If you add the others’ defense budgets altogether, their total comes to one-third or one-half of what the U.S. spends—depending on the source of the data.

If you are concerned about the burgeoning budget the Islamic State has gained over the past year from its conquests in Syria and Iraq, the sum is not publically reported, but it is not at all clear if the total for an entire year exceeds what the Pentagon spends in a single day: on average for 2014–$1.5 billion.

Also, keep in mind that Pentagon spending does not constitute all of what we devote to national security. Above the $560 billion for the Department of Defense (DOD) in 2015, add still more for nuclear weapons in the Department of Energy, military and other assistance to Afghanistan and many others from the Department of State, anti-terrorism spending in the Department of Homeland Security, caring for veterans of our past and current wars in the Department of Veterans Affairs, DOD health and retirement spending that has been shuffled over to the Department of the Treasury’s budget and more—even including defense related spending in the Departments of Agriculture and Education. It all adds up to $1 trillion.

This is not austerity.

Current U.S. spending for national defense is—quite literally—excessive, taking into account historic norms, contemporary threats and complete expenditure totals.

Anyone who calls current defense spending levels “austere” is either ignorant or misleading. To call the cuts “Draconian” is rhetorical hype amounting to pro-spending propaganda.

What Will More Spending Buy?

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, the US has spent more than $1 trillion on the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. During the same period, spending for the “base” (non-war) portions of the Pentagon budget also went up by $1 trillion over the spending rate of the first year of the George W. Bush administration.

What did we do with that extra $1 trillion in DOD’s base budget?

From 2001 to 2010 (the peak of post-9/11 spending), the US Navy’s “battleforce” shrank from 316 ships to 287; the number of fighter and attack squadrons in the active and reserve Air Force went from 78 to 63, and the number of Army Brigade Combat Team equivalents grew–but only marginally—from 46 to 48.

The weapons inventory that resulted from this shrinkage was not smaller but newer; it was smaller and older: the average age of combat ships, combat aircraft and tanks and armored personnel vehicles increased, in some cases dramatically.

The added money coincided with added bloat in senior military ranks. Since the end of the Cold War, total active duty military personnel decreased by 28 percent, but the number of general and flag officers remained constant, thereby reducing the ratio. Moreover, the number of three and four star generals and admirals actually increased from 157 to 194, a 24 percent increase. This trend adds disproportionately to cost because of the added infrastructure senior leadership demands, but—more importantly—it clogs decision-making. Historically, top-heavy militaries are ineffective; we are not improving anything with a bureaucratic culture of finding work for more senior leaders—especially when the force structure is shrinking.

Meanwhile, the training tempos and readiness of forces at the “sharp” end slipped backwards. And, in some cases the regression was huge. For example, combat fighter pilots got about half of the training time in the air they had in the allegedly “hollow military” era of the Clinton administration. Since the peak of spending in 2010, things have grown considerably worse. Army leaders have warned that few, perhaps just a handful, of brigade combat teams are ready today to conduct the combat operations they are supposed to be able to perform (and there are now just 37 of those brigade combat teams, 11 fewer than in 2010).

DOD routinely reports its low readiness to Congress; the Members’ response has been to use many accounts in the readiness-related Operation and Maintenance budget as a target for arbitrary reductions. Congress decries the plummeting readiness of our forces to justify adding money, but when it comes to spending that money to actually increase training tempos and eliminate backlogs of poorly maintained equipment, the needed money is not in Congress’ appropriations bills. Instead, most of it is fed into superfluous earmarks and hardware which Members generally deem more important and that generates thankful manufacturers amply expressing their appreciation with campaign contributions.

The problems this behavior enables have consequences. Consider the Pentagon’s track record since World War II: balance against a tie in Korea in 1953 and a victory in Desert Storm in 1991 the defeats in Vietnam and now in Iraq and Afghanistan. Furthermore, add embarrassments in Iran in 1980, Lebanon in 1983, and Somalia in 1993 balanced against victories against trivial opponents in Panama and Grenada. To cover themselves, the politicians declare the U.S. armed forces “the best in the world,” but despite individual and unit heroism at the combat unit level, we should not be nearly so boastful.

Our defense leaders’ failure to address real defense needs became clear, inadvertently, in the recent defense acquisition “reform” proposals from a group calling themselves “New Democrats.” The proposals were a series of tired nostrums, most of them floated in the past by defense manufacturers. The ideas included reducing bothersome audits of unaccounted, and unaccountable, hardware programs; inviting industry to become even more deeply involved in writing performance requirements for weapons, and asking industry to interact with DOD managers, even more than currently, to foment “mutual success” in defense acquisition.

Even more eye opening, these “New Democrats” argued that austerity “drive[s] the government to make less-than optimal spending decisions that are geared towards short-term savings rather than long-term investments.” The logic is that fewer dollars mandates bad decisions. It is like telling a welfare family to forgo food to buy a new Ferrari, and then demanding more money to address their privation.

If Congress and the Pentagon had used the extra $1 trillion they produced for themselves after 9/11 for a larger, newer, better-trained force, there would be reason to think that more spending now would address our very real problems. Instead, the money was squandered—such as on inadequate numbers of excessively complex, ineffective weapons that cost multiples of the ones they replace and too frequently underperform. In non-hardware areas, the decision-making was equally feckless and politically craven. Business-as-usual in Pentagon spending has not changed one iota; more money now is going to buy more of the same that we got in the decade after 9/11.

Moreover, there is zero evidence that anyone at the top of the Pentagon or Congress has learned any lessons. In addition to “New Democrats” proposing old bromides, the Pentagon refuses to acknowledge failed, unaffordable acquisition programs, such as the F-35 and the Littoral Combat Ship, and Congress continues to raid readiness spending to pay for earmarks and failed programs. President Obama has made himself irrelevant to the problems by calling for, not reform, but more money.

The only solution we are hearing from our defense leaders is that we must drop sequestration and spend more. Eschewing reform, they make it painfully clear that still more money will only buy a force that is even smaller, still older and yet less trained than the decayed force we now have—amazing as that may seem.

If there were to be real—meaningful and effective—reform, what would it look like? Basics would include the following:

- Financial Accountability: Almost 25 years after the enactment of the Chief Financial Officers’ Act of 1990, the Pentagon is still failing to achieve its very modest goals of a Statement of Budgetary Resources (which accountants describe as analogous to an accurate checkbook) in 2014 and a balance sheet of assets in 2017. This very incomplete effort should be augmented by routine comprehensive audits of all 77 DOD Major Defense Acquisition Programs and financial penalties for DOD components and programs that cannot be fully audited—and by career penalties for managers who preside over unaccountable programs and agencies.The current situation, where—for example—DOD relies on contractors to inform it if it has paid them properly and if their costs are reasonable, has existed for decades: current top managers find this preposterous system acceptable.

- Personal Accountability: The fundamentally corrupt practice of allowing DOD acquisition managers—in and out of uniform—to routinely leave DOD and collect money from defense manufacturers and defense-related investment firms (and their various associations) is a clear indicator of a system in serious moral decay. Similarly, Congress’ permitting its staff, especially on its four defense committees, to take a job in either the defense manufacturing world or the Pentagon makes real oversight improbable, if not impossible. Statutes to end this behavior would be simple to write—but only if there were genuine acknowledgement the behavior is corrupt. If legislated, these ideas can make real oversight inside the Pentagon and from Congress an inevitable result.

- Reverse Bloat; End Sloth: Clogging civilian and military headquarters with the gigantic numbers that exist today has resulted in a system focused on self-perpetuation, incapable of rooting out problems, adapting to change, and quickly responding to new threats, both on the battlefield and in Washington. The more we tolerate the bloat, the more we will remain paralyzed—unable to respond to the need for reform. A radical culling of politically appointed civilians, military headquarters, three and four stars and all their associated staff and infrastructure would both save real money and greatly improve the efficiency, performance and morale of those committed to defending the nation.

- Reform Acquisition: We don’t need piles of new laws and regulations as much as we need to engage in practices that we already know mean more effective hardware at affordable prices on a rapid schedule. What is needed can be described with just four words: competitive fly before buy. This means a real fly-off competition of real prototypes, and real testing, before a decision to produce. It is the anti-thesis of the highly cosmetic fly-off, buy-in, success-driven testing and political engineering of the F-35 and Littoral Combat Ship programs, among too many others. Such a reform will only succeed through elimination of the usual waivers, exceptions, dodges, and cosmetics that have made real competitive fly-offs and empirical performance- and cost-informed decisions extinct. To enable manufacturers competing with each other, it may also require some action by the Justice Department’s anti-trust division to resist further consolidation of defense manufactures, if not also some divestiture of past consolidations. The principles are simple, but because the defense manufacturers and entrenched bureaucracies hate them, they require ruthless implementation.

- Budget Restraint: There is no scarcity of money in the current defense budget, or even under further sequester levels of spending. An accountable, ethically managed system that refuses to throw money at unproven, unsound spending ideas will operate successfully at budget levels on which the existing system can only starve. More money for a failing system simply guarantees continuing dysfunction at higher budget levels.

These are only principles; once embraced, the details and the actions to achieve them become readily apparent.

Unfortunately, our current system is completely uninterested. In fact, today’s defense leaders are deeply hostile to these principles. The business-as-usual solution—more money—is the first and last choice in the Pentagon, the White House and Congress. All the predictable consequences will follow.

Here we go again.

Winslow T. Wheeler worked for Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. Senate and the Government Accountability Office on national security issues for three decades. Since resigning from the Senate staff in 2002, he has directed the Straus Military Reform Project at the Center for Defense Information and the Project On Government Oversight.