The Second Shelf

A new memoir about John Cheever reminds us that biography is at best a clumsy servant of literature.

When All the Men Wore Hats: Susan Cheever on the Stories of John Cheever, by Susan Cheever, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 400 pages.

In arranging the contents of the bookshelves that line the walls of my office, I have sought to follow what I kiddingly call the “Cheever principle”: Books by a writer are quarantined from books about that writer, including books written by the writer about himself.

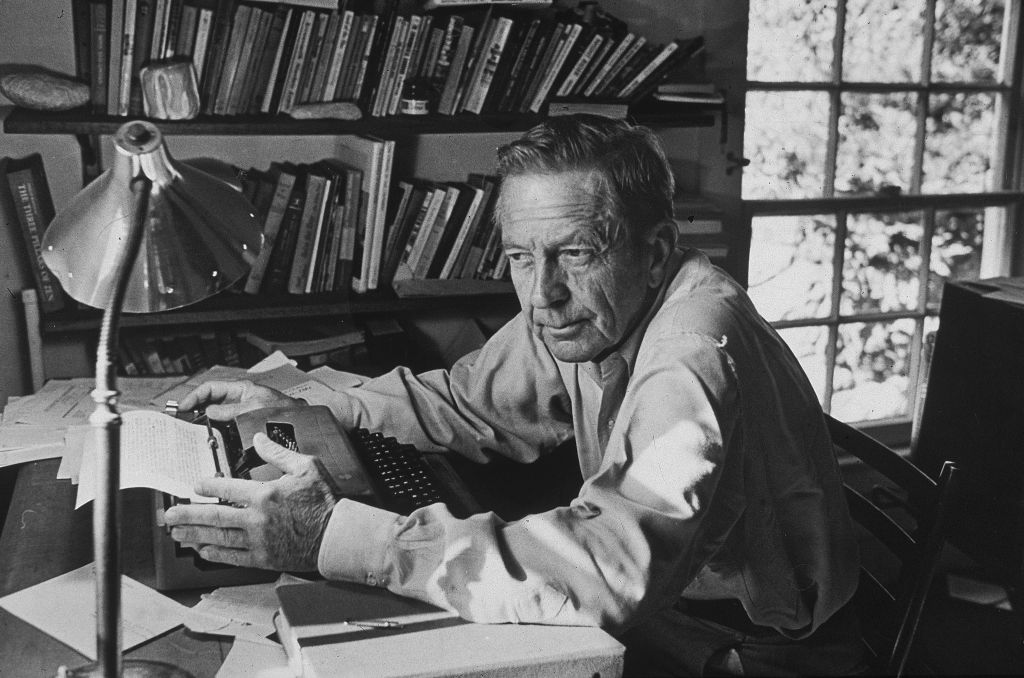

Thus, on one shelf sits a neat row of the novels and short story collections of John Cheever, the talented teller of the ecstatic dreams and terrible woes of the American upper-middle class concentrated in New England: The Wapshot Chronicle, The Wapshot Scandal, The Stories of John Cheever, Oh What a Paradise It Seems, among others. On another shelf—far away, on the other side of the room—sits an equally orderly line of books about Cheever, a married man, a dad to three children, a philanderer with members of both sexes, an alcoholic, and an irrepressible journal-keeper and letter-writer. This checkered personal history is recounted in The Journals of John Cheever and The Letters of John Cheever, whose contents were written by Cheever but not made public until after his death in 1982, as well as in various accounts of his life by others: the biographies by Scott Donaldson and Blake Bailey, and the fine memoir by his daughter, Susan Cheever, Home Before Dark.

This organizing principle is rooted in my conviction that while Cheever’s life, vacillating between normalcy and strangeness, longing for virtue and cleaving to sin, is an entirely valid subject for exploration, a thorough understanding of that life is wholly unnecessary to reckon with his fiction. Undoubtedly Cheever mined his joys and conjured his demons in stories like “The Swimmer” and novels like Falconer, but his autobiography was only relevant for him to the extent that it provided him with a jumping-off point—something from which could emanate a work broadly comprehensible to the general reader—and to us, it should not be relevant at all. If a work of the imagination is great, the originating impulse, obsession, or gripe, however consequential it was to its author and his loved ones, often seems puny.

Now comes Susan Cheever with a second volume on her father. In When All the Men Wore Hats, with the immodest and redundant subtitle Susan Cheever on the Stories of John Cheever, the author is no longer content to confine herself, as she largely did in Home Before Dark, to that which she knows best and even authoritatively: her father’s good points and weaknesses, his mysteries and contradictions. Instead, she means to supplement our sense of his stories and novels with her personal knowledge (or vice versa). At one point, she contrasts the midcentury convention in which biographies of writers proceeded with caution when making a leap from the personal to the literary with the current vogue for yoking creator to creation. “These days writers’ lives—the stories behind their stories and even the stories behind those stories—are the principal material of studying and understanding art,” she writes—and it is certainly her principal approach in the matter of her father’s work.

Susan Cheever seems motivated by the idea that to perceive properly her father’s writing, one must carry in one’s back pocket everything about him, including, but not limited to, his family background, his consuming closeness to his brother, his status as an inhabitant of (but outsider in) suburbia, his up-and-down-and-up-again relationship with his wife, and, of course, his eclectic affairs and garbled sexuality. She concedes that she comes by this view because she is related to him—a kind of divine right of a writer’s offspring. “People read his work, and they think he is actually writing to them. He understands me! He is writing to me! That’s what they think,” she writes, summarizing the desired effect of most works of fiction. “They forget that he was actually probably writing to some other real people—his family. Us! Me!” True, but what if they! and she! are not the best expositors of his writing? What if, in fact, a family’s superior knowledge of the origin story of their relative’s work has the effect of diminishing it—making it seem facile, even ordinary? Must the wondrous depths of Cheever’s great short story “The Brigadier and the Golf Widow” be boiled down to Susan Cheever’s insight about what sparked her father’s imagination: “We couldn’t afford a bomb shelter, so we had to make fun of those who had them”?

In fact, Susan Cheever reveals few great mysteries embedded in her father’s work. Instead, her revelations confirm that her father swiped from his life, not unlike most writers everywhere and at all times. Consider the case of “Expelled,” a short story inspired by its writer’s dismissal from school. “The story was ruthless in giving up people he knew for the sake of the story,” Susan Cheever writes, eagerly but pedantically. “Miss Gemmel became Miss Courtright, a ‘slightly bald’ woman who is in love with the novels of Galsworthy and who warns her young student away from the sexual reality of James Joyce.” To which many readers who already knew the story might say: “And?” One need not be familiar with such particulars to presume that the writer probably had firsthand experience with bad teachers.

By the same token, one could deduce from the abundance of fraternal relationships in Cheever’s fiction—including, as enumerated by his daughter, in such great short stories as “Goodbye, My Brother” and “The Lowboy,” to say nothing of a novel like Falconer—that the writer probably had a brother about whom he had all manner of feelings. For all the trouble Susan Cheever takes to establish the links between the real and the fictive, her analyses often elicit little more than a shrug. On other occasions, she is prone to interpret Cheever in terms amenable to twenty-first century preferences and prejudices: She works to align her father’s short story of male caddishness and female derangement, “The Five-Forty-Eight,” with the #MeToo era; the language of the present so rarely befits the attitudes and actions of the past.

There is a larger ethical question the book invites us to ponder: Was Cheever wrong to make note of the people in his life and then, material in mind, march back to his typewriter? Susan Cheever seems to have issues with this practice; she even invokes, rather lazily since the speaker was referring to a form of writing other than fiction, the writer Janet Malcolm, who said: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.” Susan Cheever recognizes the child she once was throughout her father’s work. “The little girls in his stories were not me, he insisted—although they looked like me and thought like me and did what I did,” she writes. “As I pointed out to him, they often even wore my clothes.” Later, Susan Cheever confidently claims that her mother was, for her father, a “one-woman university for the study of women—especially pretty, selfish women.” Apparently, the short story “An Educated American Woman” brought about spousal wrath. “The story of her son dying because of her negligence was too much even for my mother—a woman who by 1963 was certainly accustomed to recognizing herself in my father’s short stories,” Susan Cheever laments. “My father didn’t ask her permission, of course—it was ART and it had nothing to do with real life!”

Of course, Susan Cheever is well positioned to debunk that very notion, highlighting story after story that has its basis in family, but in a larger sense, her father was right: For most people who read it—essentially everyone outside of his own family—“An Educated American Woman” was art and not real life. From a strictly utilitarian perspective, why should the reader care if a great short story made its writer’s wife mad—what is one person’s hurt next to many thousands’ literary enjoyment? In a perverse way, to read fiction in this way is to practice a kind of lesser form of cancel culture: Art may not be canceled but it is severely diminished when experienced with the encumbrance, the homework, of knowledge of all of its makers’ shortcomings.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Susan Cheever, who again and again expresses admiration for her father’s talent and sorrow over his privations, does give John Cheever opportunities to respond. At one point, having located herself in a short story about a ski trip, “The Hartleys,” she asks her father why he killed “her” character. “For once, instead of delivering another lecture—you are reducing my literature to gossip—he seemed to ponder my question,” she writes. “He then told me that he had been afraid for me the whole time we were skiing. The story was simply an expression of his anxiety that I might get hurt.” In this one remembered kernel of wisdom from her father, there is more valuable literary criticism than in pages and pages of strained analysis. Susan Cheever’s insights into her father’s stories seem to be written for an audience of one; when she refers to “Reunion” as her favorite story of her father’s, it comes as a disappointment to learn that the reason for her preference is her conviction that the unlikable father in the story reminded her of Daddie Dearest: “In this story, the portrait of the drunken father with his bad manners, his pretension, and his selfishness is exactly a portrait of my father as we all experienced him.” The fictional father’s use of “pidgin Italian with an American accent when he is under pressure” was one of the giveaways. That’s good to know.

Susan Cheever says that her father called his love for his brother “ungainly,” and that is the best adjective to describe this book. It is a cumbersome, poorly structured hodgepodge of memoir, criticism, and biography, and in its attempts to deconstruct Cheever’s works, it reminds me of the edition of Hemingway’s short stories that presented, in tandem with the published versions, assorted discarded drafts—the flotsam and jetsam from which literary perfection was achieved. To her credit, Susan Cheever offers, in full and undiluted in an appendix, six of the Cheever stories to which she subjects her “man behind the curtain” methodology—undiluted, that is, except for the hundreds of pages that precede them.

Should this book exist? One may ask the same thing of nearly all of the posthumous Cheever publications. Reviewing Cheever’s published journals, John Updike admitted that he was gripped with the urge to close his eyes. “They tell me more about Cheever’s lusts and failures and self-humiliations and crushing sense of shame and despond than I can easily reconcile with my memories of the sprightly, debonair, gracious man, often seen arm in arm with his pretty, witty wife,” Updike wrote. Even Susan Cheever admits as much: “My father lived often in darkness, although his prose is filled with light,” she writes, but in contributing to a body of work about her father that exposes that darkness, she risks blocking out the light altogether. If we care about Cheever the writer more than we are intrigued by Cheever the man, and we should be, this book belongs, decisively, on that second shelf of mine—perhaps never to be picked up again.