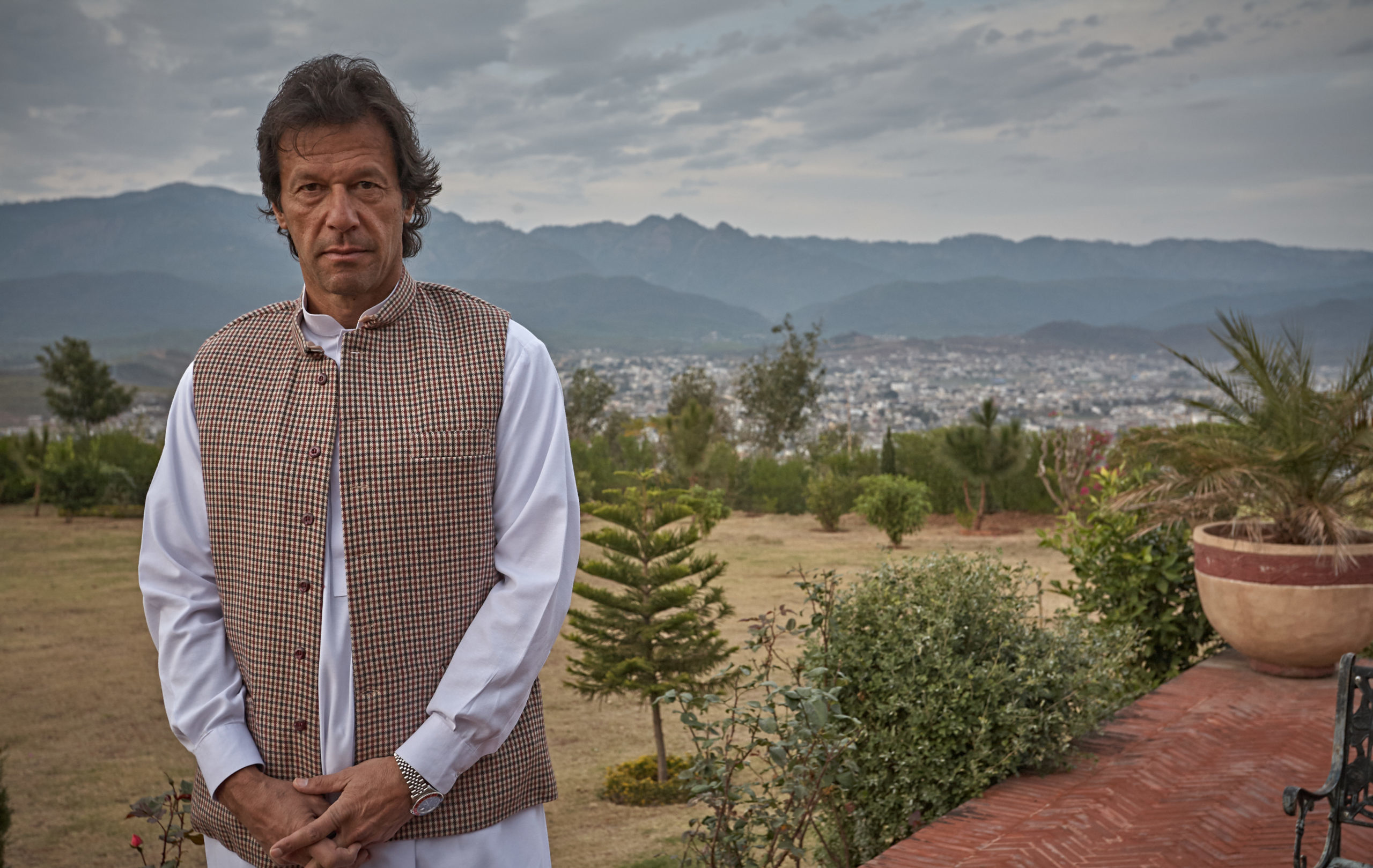

The Rise and Fall of Imran Khan

The saga of the Pakistani prime minister is a testament to the challenges populist reformers face when they gain political power.

At 39 years old, Imran Khan became a national hero. Then the captain for Pakistan’s cricket team, Khan led his heavily disadvantaged team to the knockout round of the 1992 Cricket World Cup, defeating top-seed New Zealand in the semi-finals. In the finals, Khan took the wicket to seal the championship against second-seed England himself. It was the climax of a storied cricket career that spanned more than two decades.

Thirty years removed from Khan’s shining moment, the cricket star-turned-populist prime minister has been slapped with charges under Pakistan’s terrorism laws. Khan, now 69 years old, is accused of attempting to intimidate government officials in the judiciary and police force in a public speech over the weekend relating to a case against his former senior aide. The prime minister, who was ousted from government in a no-confidence vote after a series of party defections and the loss of support from Pakistan’s powerful military, claimed former aide Shahbaz Gill was tortured in police custody. The exact charges against Khan remain unclear, and he was granted a form of bail that is paid prior to arrest. Pakistani media regulators have now ordered media outlets to stop airing the former prime minister’s speeches because of alleged “hate speech,” as Khan, much like in his 1992 World Cup run, attempts to pull off an improbable victory.

The rise and fall—and potential return—of Imran Khan is a powerful testament to the challenges populist reformers face when they gain political power. And though deep-state actors may initially prop up these political outsiders, efforts to derail their political movements kick into overdrive when the deep state is threatened with substantive reform.

Khan was born in fall of 1952. As the only boy among four sisters, Khan was quiet and understated. His upper-middle-class family provided him with a top-notch education at Aitchison College and Cathedral School in Lahore before sending him to the Royal Grammar School Worcester in England, where he began to exhibit promise as a cricket player. At the age of 16, Khan was a first-class cricketer, playing for a series of Lahore-based teams from the late '60s to early '70s.

In 1972, after being denied by Cambridge, Khan was admitted to Oxford’s Keble College to study philosophy, politics, and economics after famed Oxford English historian Paul Hayes advocated for Khan behind the scenes. From 1973-1975, Khan played for Oxford’s Blues Cricket team, and went on to play for a number of professional teams.

As a cricket star in the 1980s for Sussex, Khan became engrossed in London’s elite fashion scene and earned a reputation as a playboy. Despite Khan’s wealthy upbringing, it still seemed Khan was punching above his weight, even with his on-pitch stardom.

Shortly after Pakistan’s victory in the 1992 World Cup, Khan retired from cricket and began searching for a new pursuit. He found politics to be his new calling.

In 1996, the famed cricket star started his own political party, called Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). The newly formed party, despite its founder’s name recognition, struggled to gain traction. Khan was seen as too cosmopolitan, too Western, and too far removed from the familial and tribal-based political dynasties that dominate Pakistan’s political landscape to effectuate real change.

What’s more, Khan's new political persona was seen as inauthentic, as a '80s London playboy suddenly becoming a devout Muslim to curry favor with Pakistan’s lower classes failed to pass the smell test.

Khan’s political movement nevertheless began to gain steam in the early 2010s. The ripple effects of the financial crisis left Pakistan with a stagnating economy and a balance-of-payments crisis. Massive flooding of the Indus river destroyed much of the valley’s crops and infrastructure. An estimated 20 million Pakistanis were affected by the flood. The same year, then-Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari, the widower of Benazir Bhutto and daughter of Pakistani Peoples Party (PPP) founder Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, transformed Pakistan’s government into a complete parliamentary system, concentrating power in the hands of the prime minister, then held by the PPP’s Yousuf Raza Gilani. Two years later, Gilani would be forced to resign after the prime minister and Zardari were caught up in a massive corruption scandal.

It gave Khan’s political movement the oxygen it desperately needed. After spending the late '90s and early 2000s supporting General Pervez Musharraf’s coup and subsequent government with the belief that Musharraf would end the corruption wrought by Pakistan's longstanding political dynasties, Khan began delivering an anti-establishment, anti-corruption message of his own. In 2011, Khan’s political rallies drew crowds that numbered in the hundreds of thousands and found heavy support from the urban middle-class and university students drawn to his populist message. He spoke of a popular "tsunami" coming for the elite families that had dictated Pakistani politics for decades and argued that Pakistan should distance itself from the U.S.-led war on terror in response to increased U.S. drone strikes throughout Pakistan.

After PTI boycotted the 2008 Pakistani general election over claims the election process was corrupt, PTI picked up 35 seats in 2013, making it the third-largest party in parliament. Five years later, PTI made huge gains in the Punjab province and picked up another 114 seats, bringing the party’s total to 149. Though PTI was shy of the 172 seats needed for a majority in the National Assembly, Khan was able to form a coalition government that gave him enough votes to become prime minister.

But Khan’s rise to prime minister did not go unchallenged by Pakistan’s leading political families. Nawaz Sharif, the disgraced former prime minister who in 2017 was removed and barred from holding public office in Pakistan by the nation’s Supreme Court in connection to financial crimes stemming from the release of the Panama papers, claimed that the military, and to a lesser degree the judiciary, had interfered in the elections on PTI’s behalf. Khan’s chief political opponent in the 2018 election was Shebaz Sharif, Nawaz’s younger brother, who became the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party’s frontman in the wake of his brother’s downfall.

While Khan’s previous support for the political interventions of Pakistan’s military leaders likely gained him favor with the top military brass, the Election Commission determined there was no impropriety. Eventually, the Sharifs and the PML-N conceded.

Khan came into office with an ambitious agenda. Prior to his election, Khan announced his “100-day agenda,” outlining the reforms Khan would make immediately upon entering office. The agenda focused heavily on reviving the nation’s economy, as an overvalued Pakistani rupee and a widening current-account deficit had stressed the country’s finances. It was the third balance-of-payments crisis Pakistan had faced in a decade.

The 100-day agenda promised to lay the groundwork for the creation of 10 million jobs in Khan’s first term through infrastructure projects designed to revive the country’s manufacturing sector. For the agricultural sector, Khan’s PTI said it would incentivize farmers and ranchers to stabilize food markets. Khan also sought to reform how the country collects taxes, as many of the nation’s wealthy elite took advantage of loopholes in the tax code.

His broad, ambitious promises weren’t without specifics. Khan proposed a large development package for the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in northern Pakistan, which merged with neighboring province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa just prior to Khan’s election, which would make the tribal territory more economically productive and alleviate tribal poverty in the process.

Khan announced a six-point agenda for Karachi, the nation's largest city. The six-point plan included strengthening the country's system of law and order, enhancing local government, and building housing developments and a large public transport system.

He also sought to create a new province in Southern Punjab called Saraikistan, named for the Saraikis, who make up the majority of the proposed area. Khan’s PTI wanted to give the proposed Saraikistan significant autonomy and would use government dollars to turn the region into a major agricultural producer, providing jobs for young Pakistanis in the food-processing industry. Many of these workers would come from the neighboring province of Balochistan to fulfill job quotas reserved for Baloch peoples—a kind of olive branch to rectify relations between Baloch leaders and the national government.

But plans to make Saraikistan a reality were tabled just days before Khan came into office. While the Khan administration was able to set the table for the creation of a new province by setting up a separate administrative secretariat, ultimately his administration was unable to push this reform across the finish line. The question of whether to make Saraikistan a separate province laid dormant until January of this year, when the Senate advanced a bill supported by the PTI and the PPP to create the new province. But the issue has not yet moved forward.

And this is largely the story of Imran Khan’s tenure as Pakistani prime minister. Khan’s government would initiate populist reforms, only for those reforms to get derailed by a confluence of class interests from within government and beyond. Take Khan’s attempt to fight corruption. Once Khan entered office, the Pakistani government quickly placed Nawaz Sharif on an exit-control list so the disgraced former prime minister could not flee the country if the government exposed further corruption against Nawaz or his younger brother. Nevertheless, Mirza Shahzad Akbar, Khan’s top advisor on the interior and accountability, was pressured into resigning after the government’s investigation failed to prove corruption and money-laundering charges against Shehbaz Sharif, who replaced Khan after the no-confidence vote removed him from power.

Some of Khan’s reforms seemed successful on paper, but the projects quickly were co-opted by the country’s powerful military and intelligence arms.

As part of Khan’s first-100-days agenda, Khan tasked Pakistani Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry with reforming the country’s political-media landscape, seeking to put an end to the political censorship that characterized the state-media outlets' coverage. Those organizations often served as cheerleaders for the government, and more importantly, the military. Chaudhry’s solution was to merge the existing media-regulatory authorities, the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) and Press Council of Pakistan, into a single entity called the Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority (PMRA). But without a massive overhauling of personnel, the creation of a new regulatory authority simply placed Khan’s opponents, who serve the military-intelligence apparatus, under one roof. And Pakistani media is now censoring Khan’s speeches.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

While the cricket-star-turned-prime-minister is down, he may not yet be out. After three months of hard campaigning by Khan on behalf of PTI, the party won 15 of 20 open legislative seats in the province of Punjab, considered a political stronghold of the Sharif family, as part of a court-ordered snap election on July 17.

In another court-ordered election for Punjab, this time to fill the post of the province’s chief minister, Khan’s PTI seemed on track to pull off another stunning upset. After the first count of the 369 votes, Punjab Assembly Deputy Speaker Dost Muhammad Mazari declared that the PTI candidate had received a majority of 186 votes. But Mazari quickly backtracked and invalidated ten votes from the Pakistan Muslim League-Q (PML-Q), which gave PML-N candidate and son of the prime minister Hamza Shehbaz the electoral victory by just three votes.

The Pakistani establishment—its chosen political families, generals, spy masters, and propagandists—are throwing the book at Khan to prevent him from wielding political power again. They’ve invested too much into taking Khan out to turn back now. If Khan is somehow able to overcome the Pakistani establishment’s efforts to keep him out of power and repeats the mistakes of his first term, he will only have himself to blame.

Comments