The Real Rachman, Realist Quantum Physics, and Machiavelli’s Realism Reevaluated

Good morning, everyone. Hope your 2020 is off to a good start. First up: Samuel Graydon updates us on what is going on in quantum physics and an intriguing new “realist” explanation of the universe: “The world, Smolin says, is a relational one – that is, location and time are defined with reference to something else (‘Three blocks south of the supermarket is a relative location’). And he also claims that time is fundamental to the universe; the future is produced by present events, in a process that is irreversible. Despite our everyday experiences corroborating this – the trundling of the sun across the sky, the fact that ‘the sword outwears its sheath, / And the soul wears out the breast’ – there is in fact a reasonable argument which suggests that time is not linear at a microscopic level. But let’s roll with it – Smolin tells us he has argued this point many times elsewhere and doesn’t want to do so here. Space, then, is emergent and ‘non-locality’ can be explained as a remnant of the primordial spaceless world.”

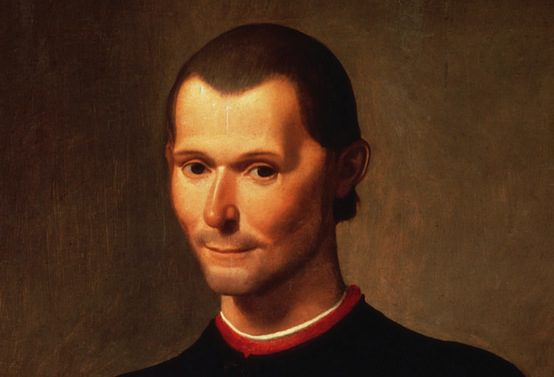

James Hankins takes stock of Machiavelli’s realism and finds it wanting: “Machiavelli’s political science has no room for philosophers, whom he considers oziosi, armchair emperors, and impractical, corrupting influences. States should be reordered by experienced men of action who are also students of history and have the analytical skills to take the correct lessons from history and experience. Machiavelli also has no interest in rising from mere survival to a life where higher and finer human capacities are actualized by the virtues. Instead of vivere and bene vivere he offers, as alternative ends of human government, survival and glory. The divine life of the mind is reduced to entertainment. Fixed habits of virtue for him are foolish and lead to ruin: the good prince must learn how to be bad when the situation calls for it, and the tyrant must learn to use the arts of good government tactically to hold on to his stato . . . The Aristotelian mean, the ‘golden mean’ of moralists, which Machiavelli calls the via del mezzo, the middle course, is one of his bugbears. It is recommended only by witless people, unfortunately numerous in civic and princely counsels, who lack understanding of politics. The middle course, according to Machiavelli, is almost always the wrong one.”

A closer look at that orb in Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi: “Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK, noted that one of his reasons for thinking the painting was not a Leonardo original was the fact that the orb didn’t refract light realistically, even though supposedly later copies of the painting did. Given the Renaissance artist’s keen interest in science, Daley said that it was unlikely that ‘Leonardo knew all about the optics, but just decided not to bother.’ At the time, Christie’s countered that Leonardo’s paintings were ‘known for their mystery and ambiguity,’ positing that ‘he chose not to portray it in this way because it would be too distracting to the subject of the painting.’ Now, however, a paper by Marco Zhanhang Liang, Michael T. Goodrich, and Shuang Zhao claims to have determined that the mysterious translucent globe in Christ’s hand may be scientifically accurate after all.”

Mary Norris praises a “passionate” guide to ancient Greek.

Lance Robinson reviews Clay Risen’s “rollicking” book on Theodore Roosevelt and The Spanish-American War.

Steven Knepper reviews Gordon Marino’s Existentialist’s Survival Guide: “Marino teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College and curates the Hong Kierkegaard Library. He has spent decades writing about the existentialists. His passion for them did not begin in the classroom, though. After a failed relationship, with derailed careers in both boxing and academic philosophy, a young Marino struggled with suicidal thoughts. While waiting for a counseling session, he spotted a copy of Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love on a coffee-shop bookshelf. He opened it to a passage in which Kierkegaard criticizes a ‘conceited sagacity’ that refuses to believe in love. Intrigued, Marino hid Works of Love under his coat on the way out the door. He credits the book with saving his life.”

Essay of the Day:

In The New York Review of Books, Caryl Phillips writes about the real Rachman behind “Rachmanism”:

“In the early hours of November 29, 1962, Peter Rachman, a Polish-born property developer, was driving his Rolls-Royce home toward Hampstead Garden Suburb, north of London, when suddenly he felt ill. The bald, corpulent man pulled over to the side of the road and, sweating heavily, spent some time doubled over the steering wheel. After a short while, Rachman felt well enough to complete his journey. Once he reached his mock-Georgian mansion on fashionable Winnington Road, he took to his bed. At 9:45 the next morning, after a fitful, uncomfortable night, Rachman suffered a heart attack and his wife, Audrey, called for an ambulance. Rachman was admitted to Edgware General Hospital; at 4:45 PM, he suffered a second, this time fatal, heart attack. He was forty-three years old.

“The following Thursday, Rachman was buried in Bushey Jewish Cemetery in Hertfordshire. There were only a handful of mourners, principally his wife and some members of her family. Peter Rachman had arrived in Britain sixteen years earlier as an impoverished ex-serviceman, and had remade himself to the extent that, at the time of his death, he was a successful businessman who habitually sported diamond cufflinks, tailored suits, and crocodile-skin shoes. Despite such sartorial flamboyance, Rachman’s was a private life, and he remained largely anonymous. There were no obituaries, and no public acknowledgement of his passing. This would soon change. Within a few months of his death, the British public would become extremely familiar with the name of this Polish émigré, but his posthumous fame was hardly flattering.

“On July 14, 1963, The Sunday People published a lead story supposedly exposing the late businessman’s nefarious practices under the banner headline ‘Rachman—These Are the Facts.’ The paper identified Rachman as a central figure in an ‘empire based on vice and drugs, violence and blackmail, extortion and slum landlordism the like of which this country has never seen and let us hope never will again.’ With no fear of a libel suit from a dead man, other newspapers followed and targeted Rachman, although there were plenty of examples of unscrupulous landlords at work in London. The day after The Sunday People’s splash, the BBC broadcast an episode of its flagship investigative program Panorama that depicted Rachman as a degenerate racketeer in tinted glasses, with a cigar in his mouth and a roll of banknotes in his pocket.

“The BBC reported that in order to extract maximum profit from his houses, Rachman would not hesitate to ‘Put in the schwartzers’—as those in the real estate world commonly termed the practice of letting their properties to black people, so that rent-controlled white tenants would feel they had little choice but to leave, enabling the landlords to let out their flats at a higher rate. Panorama reported that, if this didn’t work, Rachman would pay Caribbean immigrant tenants to play deafening music at all times of the day and night. The BBC also reported claims that Rachman hired black hoodlums to intimidate white tenants, or, conversely, white hoodlums to harass black tenants; and if these tactics failed, Rachman would employ thugs with Alsatian dogs to wrench doors off their hinges, remove roof tiles, and rip up floor boards in order to terrify those he wished to evict.

“Privately, Rachman’s friends and associates were appalled by the denigration of the generous and kind man they had known. However, wary of having their names similarly tarnished, most were unwilling to speak up in the dead man’s defense. One notable exception was Serge Paplinski, a fellow Pole and Rachman’s righthand man in the property business. Paplinksi gave an extensive interview to the News of the World, another Sunday tabloid, which eventually declined to publish any portion of it because it painted Rachman in a positive light.”

Photo: Quadrantids over the Great Wall

Poem: Christian Wiman, “Even Bees Know What Zero Is”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.