The Reagan Revival We Need

It was the GOP convention of 1976. Ronald Reagan had just completed his departing remarks after losing a narrowly fought and bitter bid for the presidential nomination, when a woman on the convention floor exclaimed, “Oh my God, we’ve nominated the wrong man!’

According to an able Reagan field man, Kenny Klinge, the woman standing next to him in Kansas City was, as he described, an enthusiastic “big time” supporter of the incumbent Gerald Ford. She was not alone; most likely there were many more Ford supporters who were stunned by Reagan’s impromptu, now historic and moving speech.

.Reagan’s dream seemed impossible that night, and one can only imagine how he felt as he walked out of the Kemper Arena. What Reagan, or any of us, could not have known was that he may have lost the battle in 1976 but he would eventually win the war of 1980.

Reagan was a political outsider when he ran for the Republican nomination. Thanks to party machinations, however, Reagan was narrowly outdone at the 1976 convention by Gerald Ford. It was a decision Republicans quickly came to regret as Ford and the party’s old guard lost to Jimmy Carter that November. To say many Republicans had buyer’s remorse was the understatement of the year.

Reagan’s loss in Kansas City had only invigorated his determination to make a comeback, and he spent the next four years laying the foundations for his next move. As discussed in my book Reagan Rising, the Gipper began planting the seeds of his victory right after Ford’s loss. He introduced the concept of a “New Republican Party” that could appeal to regular people and the working class, not just the corporate board members and country club socialites who had traditionally formed the GOP’s electorate. It foreshadowed the rise of the “Reagan Democrat” that was key to his landslide victory in 1980.

There was, of course, a primary to get through, and for Reagan the biggest obstacle was George H.W. Bush, scion of the Republican establishment and a decidedly more liberal Republican than Reagan. Bush had an early lead in the primaries, winning the Iowa straw poll and carrying Puerto Rico. Going into New Hampshire, in one of the campaign’s most memorable episodes, Reagan decided to pay for a debate among all of the GOP contenders. However, Bush did not want any other candidates on stage, and when Reagan tried to explain his reasoning, the editor of the Nashua Telegraph ordered Reagan’s mic to be cut off. This caused him to deliver his immortal line “I’m paying for this microphone Mr. Green!” The saturation media coverage of that zinger led to Reagan handily winning the Granite State.

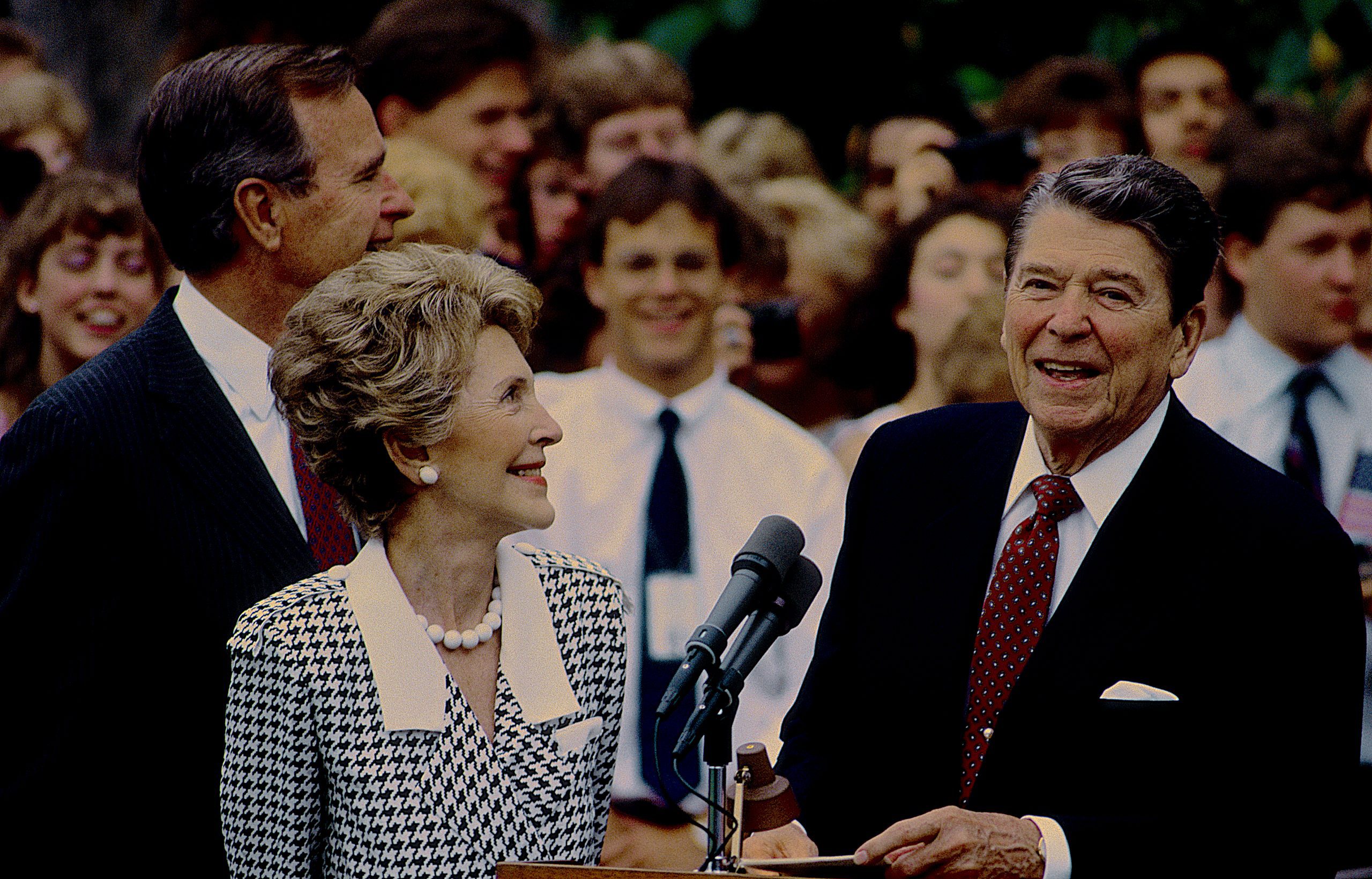

Bush and Reagan developed into intense rivals with Bush going so far as to call Reagan’s economic platform “voodoo economics.” But despite winning Massachusetts and several other primaries, Bush could not surpass Reagan’s lead with the delegates. By May, Reagan’s momentum was too great, particularly after winning the major Southern primaries. Despite the rivalry and his convention victory, Reagan was wise enough to pick Bush as his running mate, knowing that Bush could appeal to moderates and right-leaning Democrats who were put off by Reagan’s social conservatism, and produce a unified convention.

For me, I was but a foot soldier in the Reagan Revolution in 1980. After knocking about conservative causes for several years, I was part of a huge upset in New Hampshire in 1978, when the longest of longshots, Gordon Humphrey, defeated 16-year incumbent Democrat Tom McIntyre. Afterwards, a group of other young conservatives—Bob Heckman, Ralph Galliano, and John Gizzi—running the Fund for a Conservative Majority—asked me to head up an independent expenditure campaign in support of Governor Reagan, in the early primaries.

It was a call that set the course of my career for the next 40 years, though at the time, it was inconceivable how significantly the Gipper’s presidency and legacy would impact my life and so many others.

After Reagan was upset by moderate Ambassador George H.W. Bush in Iowa’s caucuses—with his campaign reeling and in debt—the decision by the fellas at FCM now seems prescient. Reagan was in trouble and needed help. In a decrepit studio in Georgetown, I worked feverishly to produce 30-second and 60-second radio commercials plugging his candidacy, and then bought $700,000 worth of time on every imaginable AM radio show—especially news, sports, weather, and farm reports—in New Hampshire, South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Illinois; early and important primary states.

In the meantime, the guys at FCM produced print ads, flyers, brochures, and press releases all touting Reagan. And Reagan won all those primaries—by big margins. By the time of the Illinois primary, Reagan had regained his footing, was off and running, and it is heartening to think that Bob, Ralph, John, and I came to the Gipper’s rescue at a time when he needed help the most.

Due to the convoluted FEC laws, I could not go to work for the official campaign after working for an independent expenditure, so I had to bide my time, work on other races around the country, and then went to work at the RNC in early 1982 to help coordinate with the political and communications offices of the Reagan White House. The good news is I went to Arizona—briefly—to pitch in on a House race. While there, a most important event occurred; I met my wife Zorine, who was also working on the campaign. Thirty-nine years later we are still happily married, both proud veteran Reaganites.

The stage was now set for a fall showdown between Carter and Reagan, but for much of the campaign Carter held a steady lead in the polls. Despite having fought off a challenge from Sen. Ted Kennedy, Carter and the Democrats were confident they could trounce Reagan.

The Reagan campaign of 1980 was touch and go for the entire year. First, Jimmy Carter was up considerably, then Reagan was up. It was a seesaw battle and most thinking people assumed, in the end, that Carter would prevail.

Few of the East Coast elites thought well of Reagan. Mostly, in the newsrooms of The Washington Post and The New York Times and on the campuses of the Ivy League colleges, Reagan was dismissed as a lightweight who would draw us into a nuclear war. The doom and gloom of the media and educational classes has, alas, not changed in 40 years. If anything, they’ve become more pigheaded, illiterate, and naive. Reagan always knew who his enemies were: the pseudo-intellectual elites; the kommentariat.

Carter and the media made the mistake of viewing Reagan as some kind of novelty, an outsider who would never pose a serious threat. This mistake would come to haunt Carter when he and Reagan would face off for their one and only debate on October 28, 1980, one week before the election. At the time, it was the most watched debate in U.S. history, and stands today as the second-most watched debate.

The Carter-boosting Washington Post produced a questionable poll the morning of the debate, saying that the incumbent had jumped into a new lead, but few took it seriously.

The election was, in fact, tied at that point, although Carter had momentum on his side. However, electoral momentum is as fickle as a stormy sea, and Carter’s lead evaporated like a receding tide when he went on stage that night.

During the 90 minutes before an audience of millions, Reagan successfully argued his case to the American people; the country was in a rut and desperately in need of a shot in the arm. While Reagan pushed new ideas and a message of optimism, Carter fumbled his chance to torpedo Reagan’s hopes, only offering that he apparently took nuclear policy advice from his then-12-year-old daughter. Reagan ended the discussion with his question to the voting audience: “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”

The resounding answer from the American people was “No!” After four years of Soviet advances, long gas lines, high inflation, high interest rates, high unemployment, and high jinx from the stumbling, bumbling Carter White House, and malaise, the American people knew they were ready for a new beginning and to make America great again.

They wanted jobs, they wanted to keep the value of their hard earned buck, and they wanted to respect their president again. They wanted someone who could give them back the pride and sense of hope that is integral to the American story. They wanted someone who would stand up to the thuggish Soviets. Reagan gave the American people all that, and more, and along the way became one of our greatest presidents. He helped set the stage for the fall of the Evil Empire that was the Soviet Union, freeing millions imprisoned behind the Iron Curtain, and brought prosperity and hope back to America.

.Someone once quipped that if you asked Reagan and Carter what time it was, Carter would tell you how to build a watch but Reagan would say, “It’s time to get this country moving again!” Reagan knew leadership was all about inspiring people. The elites hated it but the American people loved it.

Reagan demolished Carter, winning in a landslide of unbelievable proportions. Not only did he carry the stalwart conservative states, but he also won traditionally Democratic strongholds in parts of Massachusetts, New Mexico, Washington state, and Illinois. The term “Reagan Democrat” entered the lexicon, thanks in no small part to Reagan’s call for Republicans to broaden their reach through a “coalition of shared values.”

Just to show it was no fluke, he won four years later by an even bigger landslide, drowning Walter Mondale 49 states to Minnesota. (Reagan’s 1984 campaign manager, Ed Rollins, will tell you even today that they voted graveyards in the Golden Gopher State, delivering it to Mondale by a scant margin. But Reagan, ever the gentleman, would not allow a recount in Minnesota.)

After four years—40 years ago, if it is possible—the impossible dream of conservatives came true. Years of frustration and disappointment with “Mr. Republican” Senator Robert Taft, and with “Mr. Conservative” Barry Goldwater, vanished as conservatives pinched themselves over the election of their leader, Ronald Reagan.

All things being equal, the American people do not like to throw an incumbent president out of office. Not without good reason, anyway. In the 20th century, only in 1932 and 1980 did the voters find sufficient reason to boot the elected incumbent in a two-man race. The elections of 1912 and 1992 were aberrations, due to the presence of a major third-party candidate. The election of 1976 was also an aberration, as Gerald Ford had never been voted into office in the first place.

All things being equal, the American people do not like to throw an incumbent president out of office. Not without good reason, anyway. In the 20th century, only in 1932 and 1980 did the voters find sufficient reason to boot the elected incumbent in a two-man race. The elections of 1912 and 1992 were aberrations, due to the presence of a major third-party candidate. The election of 1976 was also an aberration, as Gerald Ford had never been voted into office in the first place.

The words of a Civil War Yankee soldier come to mind, recounting years later, “Was it possible? Did we really do these things?” The extraordinary road to Reagan’s victory in 1980 and the election itself still remain significant because they brought people together. We can look back to the story of the 1980 campaign and see that it created unity, a foreign concept to modern American politics. It brought intra-party rivals together into a winning coalition, and it brought Democrats and Republicans together nationally and led to eight years of stability and good will.

As we reach the zenith of what has been a tumultuous election year, remember that such wonderful things have happened before, and they will happen again. It’s interesting how, on the 40th anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s triumphant landslide in 1980, we have another contest of such historic proportions. Just like today, an enormous amount was at stake. Back then, Republicans were still reeling from the Nixon days, and thanks to Jimmy Carter’s poor management skills, the Democrats looked like the party of historic inflation, an unprecedented gas crisis, an emboldened Soviet Union, and to top it all off, an incumbent president who had the gall to tell Americans that the country’s best days were behind them.

Americans looking for good will today may not find it in the current election, but they should take comfort knowing our country has come together before. As Reagan demonstrated, with patience and principled campaigning, it can come together again.

Craig Shirley is a Reagan biographer and presidential historian. He is the author of five books on Reagan as well as the New York Times bestseller, December, 1941. He is currently working on several more books on Reagan as well as April, 1945. He is the Visiting Reagan Scholar at Eureka College, lectures often at the Reagan Library, and is the Chairman of Shirley & McVicker Public Affairs.