The Conservative Case for Antitrust

On the campaign trail in 2016, Donald Trump did not sound too far from Bernie Sanders. Trump appealed to working class voters telling them, “It’s not just the political system that’s rigged, it’s the whole economy.”

In part of his message, he promised to oppose mergers: “As an example of the power structure I’m fighting, AT&T is buying Time Warner and thus CNN, a deal we will not approve in my administration because it’s too much concentration of power in the hands of too few.”

It was a sharp departure from the speeches of recent Republican presidential candidates such as Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush or George W. Bush. Some commentators fretted that Trump was abandoning conservative tradition. Trump was in fact returning to the American and Republican traditions of opposing monopolies and industrial concentration.

The thread opposing monopolies and concentrations of power runs from to the founding fathers to the present day. The Boston Tea Party was in response to the Company’s monopoly on tea. James Madison believed in economic rights; and in an essay, he warned against “arbitrary restrictions, exemptions and monopolies.” The Maryland State Constitution in 1776 declared, “Monopolies are odious, contrary to the spirit of free government … and ought not to be suffered.” When the Continental Congress issued its Declaration of Independence from Britain, they resented the monopoly of the East India Company.

Thomas Jefferson was in Paris during the Constitutional Convention, and he wrote to Madison his misgivings that the Constitution included no Bill of Rights, “First, the omission of a bill of rights, providing clearly, and without the aid of sophism, for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction against monopolies [emphasis added]….” For Jefferson, the freedom from monopolies was as important as First Amendment rights.

John Steele Gordon, a historian of American business, noted that Democrats are perceived as the party of antitrust, “Yet it was Republicans, in both Congress and the White House, who led the way to finding an effective regulatory system for these big businesses.”

Gordon is right. Believe it or not, Republicans controlled Congress and the White House in 1890 when they passed the Sherman Antitrust Act.

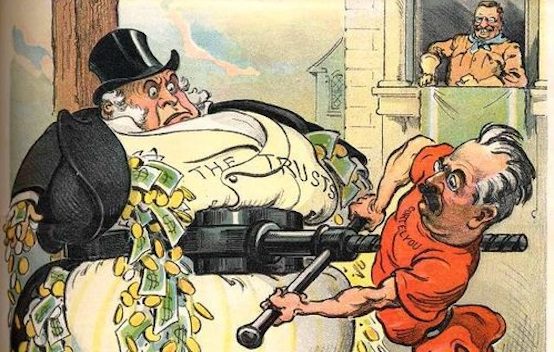

The Act was sponsored by Republican Senator John Sherman of Ohio. In the senate debates in 1890, he declared, “If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life. If we would not submit to an emperor, we should not submit to an autocrat of trade, with power to prevent competition and to fix the price of any commodity.”

A few years later in 1900, antimonopoly policy was a firm part of the Republican platform when Republican William McKinley faced William Jennings Bryan, “…we condemn all conspiracies and combinations intended to restrict business, to create monopolies, to limit production. or to control prices; and favor such legislation as will effectively restrain and prevent all such abuses, protect and promote competition and secure the rights of producers, laborers, and all who are engaged in industry and commerce.”

President Theodore Roosevelt, a Republican, launched 45 antitrust suits. His successor, President William Howard Taft, also a Republican president launched 90 antitrust lawsuits. In the 1912 election Theodore Roosevelt ran for President as a progressive on a trust-busting platform arguing for the need to control corporate power and end monopolies.

After a long Democratic reign under Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman, the Republicans regained the presidency with Dwight Eisenhower. As the leading general in Europe, Eisenhower broke up German monopolies and cartels. As President, Eisenhower wanted a dynamic market economy, antitrust policy played an important role.

The Republican platform of 1952 argued that Democrats had abused antitrust laws, and they claimed they would enforce them better:

We will follow principles of equal enforcement of the anti-monopoly and unfair-competition statutes and will simplify their administration to assist the businessman who, in good faith, seeks to remain in compliance. At the same time, we shall relentlessly protect our free enterprise system against monopolistic and unfair trade practices.

Once Eisenhower became president, the Department of Justice (DOJ) investigated antitrust enforcement and found no evidence antitrust was politicized.

A year later, in 1953, the Eisenhower Administration filed the Oil Cartel cases, contending that the two Standard Oils and three other companies were fixing prices. His administration also launched criminal price-fixing conspiracy cases against General Electric Company, Westinghouse Corporation, and a number of smaller electrical equipment manufacturers. Unlike today, many high-level executives went to prison. The message was clear: antitrust compliance was a matter of critical importance.

In Eisenhower’s last State of the Union address attributed the strength of the U.S. economy to his administration’s “vigorous enforcement of antitrust laws over the last eight years and a continuing effort to… enhance our economic liberties.”

The Ford administration filed a monopolization suit against AT&T and signed major new antitrust legislation. He increased damages for anticompetitive conduct. He also supported the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, which created a new system of pre-merger notification enabling the antitrust agencies to investigate every significant merger before it took place. The Act represented a big shift in merger enforcement activity, away from litigation years after a mergers towards advance review.

In the early 1980s, everything changed. The Republican platform has come to ignore antitrust and the dangers of highly concentrated industries. The Chicago School took over antitrust, and since then, antitrust enforcement has not so much collapsed as thudded into the abyss. The Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission is often staffed by people who have gone through the revolving door and view their job as helping approve mergers.

Republicans are generally thought of as the party of business and fierce supporters of capitalism. Yet over time by blessing egregious mergers and increasingly concentrated industries, they have become supporters of monopolies and less competition.

The reason to support vigorous antitrust enforcement is not merely American and Republican tradition, but the support of capitalism with free, open and competitive markets.

According to the dictionary, capitalism is “characterized by the freedom of capitalists to operate or manage their property for profit in competitive conditions.” In America, the battle for competition is being lost. After four separate mega merger waves in the last forty years, industries are becoming highly concentrated in the hands of very few players, with little real competition. This goes against capitalism.

Markets have shifted to monopolies and oligopolies when it comes to selling goods, but it is just as bad when you look at the power of companies as buyers. When workers have fewer employers to choose from in their line of work, their bargaining power disappears. Corporate giants can squeeze their suppliers, but the main things companies buy is labor, and they have been squeezing workers.

If Adam Smith’s invisible hand required many buyers and sellers to find the right price, then the invisible hand has gone missing as we have moved towards oligopolies.

Fewer competitors leads to less competition and more collusion. There is nothing new under the sun. Even in the 18th century, Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations that, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” A little later John Stuart Mill echoed the sentiment, “Where competitors are so few, they always end by agreeing not to compete.”

Capitalism without competition is not capitalism.

Competition creates clear price signals in markets, driving supply and demand. It promotes efficiency. Competition creates more choices, more innovation, economic development and growth, and a stronger democracy by dispersing economic power. It promotes individual initiative and freedom. Competition matters because it prevents unjust inequality, rather than the transfer of wealth from consumer or supplier to the monopolist. If there is no competition, consumers and workers have less freedom to choose.

Capitalism is a game where competitors play by rules that everyone agrees. Today, the state, as referee, has not enforced rules that would increase competition, and through regulatory capture has created rules that limits competition. All too often today, monopolies exist through lobbying, regulation and the helping hand of government.

It is worth remembering that when Adam Smith wrote of “the invisible hand” in The Wealth of Nations, he was not simply praising the free market, but condemning the government acting on the behalf of large merchants who were furthering their own interests.

Smith was not the last great economist to praise competition. The Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek was a believer in free markets and railed against concentrations of power. He believed that inevitably once economic power was consolidated, the monopolies and cartels would become “governmental instrumentalities to achieve political ends.”

Conservatives should be humble about the limits of knowledge. Friedrich Hayek argued against government monopolies “knowledge problem” as an insurmountable barrier to central planning. No one person or government could know everything because knowledge was distributed. However, private monopolies also suffer from the knowledge problem. More competitors is the answer to the monopoly problem.

The conservative case for competition is also political. Broken markets create broken politics. Economic and political power is becoming concentrated in the hands of distant monopolists. The stronger companies become, the greater their stranglehold on regulators and legislators becomes via the political process. This is not the essence of capitalism.

When economists promised mergers and monopolies would create efficiency, Hayek wrote, “Personally, I should much prefer to have to put up with some such inefficiency than have organized monopoly control my ways of life.”

Milton Friedman, the arch free marketer, wrote, “Economic freedom is an essential requisite for political freedom. By enabling people to cooperate with one another without coercion or central direction, it reduces the area over which political power is exercised.”

The principal reason for supporting free markets was not lower prices or consumer welfare, but strengthening of democracy and freedom. “In addition, by dispersing power, the free market provides an offset to whatever concentration of political power may arise. The combination of economic and political power in the same hands is a sure recipe for tyranny.”

Later in life, Friedman changed his views on monopolies. It is the great irony of history that, while Friedman loved competition, his disciples have done so much to concentrate power and to convince conservatives that monopolies are good.

Jonathan Tepper is a senior fellow at The American Conservative, founder of Variant Perception, a macroeconomic research company, and co-author of The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition. This article was supported by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors.