The Confused Cynicism of Slenderman

Without quite being aware of it, humans dream meaning into the world together. The stranger parts of our own minds are engaged in occult dialogue with the minds of others, mostly through narrative stories. Call them folk tales, fairy tales, or urban legends. Our collective fears and hopes are in conversation with one another. Bruno Bettelheim wrote in the introduction to his classic The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales that “Contrary to the ancient myth, wisdom does not burst forth fully developed like Athena out of Zeus’s head; it is built up, small step by small step, from most irrational beginnings.” It takes time for folk legends to develop, to be properly filtered through the minds of the folk themselves, and to use the energy of their irrational (maybe pre-rational would be a more appropriate term) origins as a kind of energetic life pulse sustaining the vitality of the stories themselves.

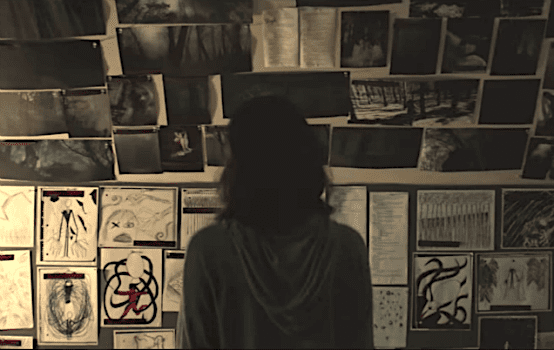

Perhaps the most recent character to enter our collective folk imagination is Slenderman, the faceless, gaunt internet meme in a bespoke suit who simultaneously rescues and kidnaps children. The conversation about Slenderman has been conducted primarily over the internet, only occasionally making appearances in documentaries and news specials. Most recently, Sony Films released a full-length feature called Slenderman, adding an interesting complication to the folk mythos of the character. What happens when folktales are sold back to the folk as Hollywood product?

Unlike classical folktales and modern urban legends such as Bloody Mary, Slenderman can actually be traced back to a specific creator. Eric Knudson, posting under the pseudonym “Victor Surge” in the online forum Something Awful in 2009, submitted two black and white images to a Photoshop contest that depicted groups of children and the now-recognizable figure of Slenderman lurking in the background. The caption of one of the images read: “’We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time…’—1983, photographer unknown, presumed dead.” The captions provided a story for the images and outlined the basic themes of the Slenderman mythos: an ageless creature that both steals children and causes them to commit horrific acts, his image itself containing some sort of pestilential supernatural power.

Being traced back to a specific creator isn’t the only thing that makes Slenderman different from traditional folk tales and urban legends. There’s also the internet. After appearing on Something Awful, Slenderman quickly became a meme, his mythos (referred to as the capitalized “Mythos” by those who engaged with it) passed along, modified, and policed by often anonymous online posters. Countless images of the figure, mostly black and white, were created and disseminated. Instead of springing from the collective and often rural imaginations of a people and then subsequently spread orally, Slenderman is a textual and visual folk icon that is “aware,” as it were, of its own origins. Thus, University of Indiana professor Jeff Tolbert writes, “Slender Man subtly references the self-conscious communicative processes that gave rise to the tradition itself and are, in fact, the reason for its continued existence as an internet icon.”

Videos, video games, and documentaries have been made of Slenderman, but Sony Pictures’ recent release is the first full-length feature Hollywood treatment of the character. Unfortunately, it’s a total failure, mostly due to the fact that it can’t decide what it wants to add to the Slederman mythos.

The plot of Slenderman is fairly simple. A group of teenage girls living in Massachusetts, bored and hanging out one night, “summon” Slenderman by watching a video they find online. They all seem freaked out by the experience, but when Katie, who has an alcoholic father, goes missing during a field trip, things begin to get very strange. The other friends slowly, one by one, come to accept that Slenderman is real and has taken their friend. They go into the woods, the mythical home of Slenderman, and offer him things of personal value (a photo of a deceased father, a blanket from a sibling who died in childhood, a very meaningful piece of pottery) with the caveat that they can’t actually look at Slenderman and must remain blindfolded. Of course, one of the friends, Chloe, looks and subsequently loses her mind. The two remaining friends, Wren and Hallie, argue back and forth about the reality of Slenderman before meeting (intentional vagueness to avoid spoilers follows) dramatic conclusions of their own.

Despite being a failure, there are things to like about the movie. The second unit has something of a small triumph, capturing a wealth of moody images suffused with a typically New England gloominess that sets the tone for the main narrative of the film. It has an appropriate “feel.” And the young actresses who portray the friend group are outstanding. Annalise Basso, who plays the character Katie, is a future star in the making who has already become something of a workhorse in the horror genre, having already appeared in such films as Ouija: Origins of Evil and Occulus. And Joey King, who acts as Wren in the film, plays a pitch-perfect teenage girl who is slowly losing control of her senses as her friends distance themselves from her.

The fault lies not with the actors or crew, but with the script itself. Simply put, the film can’t decide which aspect of the wide Slenderman mythos it wants to engage with. A significant element of the story as it’s told in creepypastas is that Slenderman provides some sort of refuge for suffering children. That usually means that he protects kids who are being bullied and offers them a chance to escape to his home in the woods. But there’s also a Pied Piper element to it all: it’s sort of ambiguous as to whether the children are being rescued or stolen. The film begins by working within this trope, with the character Katie—the first girl to go missing—wanting nothing more than to escape her small town life and alcoholic father. But by the end of the film, when Hallie the all-American jock is being tormented as well, the message seems to have shifted to making Slenderman a metaphor for the dangerous allure of the internet itself. So which is it? Is Slenderman a warning about children who fall through the cracks, or an amorphous fear that the internet itself is a kind of virus (a buzzword often used in the film) affecting our children, none of whom are quite safe? Wallowing in the Slenderman mythos without quite knowing what it wants to say has very real and detrimental technical consequences for the quality of the film. As Corey Kloos, a young filmmaker, commented to me, Slenderman can’t decide who its protagonist should be. That’s because it never tells us what Slenderman means.

The film fails, but some wanted to put a stop to it before it was even made. Because of the now famous non-fatal 2014 Waukesha, Wisconsin, stabbing of a 12-year-old girl by her two friends, which HBO documented in Beware the Slenderman, some thought it inappropriate that Sony Pictures should profit off a story that led two young girls to such a grisly crime. A petition circulated demanding the film not be released, calling the Sony product “crass commercialism at its worst,” a “naked cash grab built on the exploitation of a deeply traumatic event and the people who lived it.” Bill Weier, the father of one of the Wisconsin girls who stabbed their friend, said, “It’s absurd they want to make a movie like this…. All we’re doing is extending the pain all three of these families have gone through.” In capitulation, the film won’t be shown in the Wisconsin counties near to where the stabbing occurred.

But the real problem of the film isn’t insensitivity to the horrific violence in Waukesha. The plot of Slenderman itself doesn’t bear any resemblance to the events in Wisconsin. And furthermore, an appropriate amount of time has passed since the crime to justify a reexamination of the character himself. The real problem with the film, beyond its perceived insensitivity and fumbling incoherence, is that it’s a kind of cultural theft, selling the stories we’ve collectively created for ourselves back to us as a product. Utah State University folklorist Lynne S. McNeil writes, “The emergence of traditional expressive forms on the Internet, and the observation and re-creation of them by other people in new contexts, has not gone unnoticed by the Internet community itself, which has adopted the concept of memes to identify what folklorists would call folklore.” Slenderman is a character in a narrative that we, the folk, have created among ourselves as part of an elaborate textual and visual conversation. It’s no wonder that a single film struggles to compete with that complexity. It’s almost cynical of them to even try.

Scott Beauchamp’s work has appeared in the Paris Review, Bookforum, and Public Discourse, among other places. His book Did You Kill Anyone? is forthcoming from Zero Books. He lives in Maine.