Stan Evans: Right From the Beginning

My apologies in advance to my original conservative compatriots Doug Caddy and Bill Schulz for any minor inaccuracies in this account of our early escapades with M. Stanton Evans, who departed this world on March 3, 2015. Any such mistakes are not intentional, but the result of a memory that was never too good to begin with, further impaired by 58 years of perhaps too many beers and vodka martinis. Live with it—or risk a mouth punch (see below).

The year was 1957, and we were the very first Human Events journalism class taught by Stan Evans. Thousands of students followed us over the decades, but there was nothing like that first time. For the next several years, we three students would have daily contact with Stan as our teacher and mentor, our friend, and our on-and-off roommate. What a blessing.

American conservatism as a “movement” didn’t really exist at that time. It was an intellectual idea conceived by William F. Buckley Jr. when he launched National Review several years earlier in 1955, the name bestowed by NR Senior Editor Russell Kirk in his book The Conservative Mind. There wasn’t even any consensus on the moniker “conservative.” I considered myself an individualist, others considered themselves libertarians or classical liberals. The Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI) existed to provide intellectual fodder for us youngsters, but there were as yet no conservative activist organizations. We would help remedy that deficiency in the coming years 1957 to 1960. We were there at the creation.

What a blessing! I cannot imagine how boring it would be to be a teenager with too much energy and too little sense, where my biggest decision was whether to pursue history or math as my major. We were out to conquer the world, or at least to change it! We weren’t “normal” students.

Soon after the three of us arrived in Washington, Stan gave us our instructions on what we were going to do as activist journalists: “First, we take over the Young Republicans. Then we take over the Republican Party. Then we take over the nation. And then we defeat world communism.”

I am not making this up. You can’t make up something that preposterous and that precocious and that audacious.

Human Events

We were the first Human Events Journalism Class, offered work scholarships to write for Human Events while we finished our undergraduate studies. Our pay was a pittance, but young people have a way of overcoming inconveniencies like that. You simply cut out all human nourishment but beer and pizza.

Human Events at that time was an eight-page weekly newsletter—a four-page news section on what was going on in Washington and national politics, and a four-page article, written by a different person each week. Its circulation was only a few thousand, but it kept the right alive between World War II and the formation of the National Review-Goldwater movement.

Human Events actually began as a series of Human Events Pamphlets published right after World War II in Chicago, the creation of Henry Regnery of later book publishing fame; Robert Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago; Felix Morley, long-time editor of the Washington Post (hard to believe!); and journalist Frank Hanighen. They soon changed to the newsletter format, moved the offices to Washington, D.C., and installed Hanighen as editor.

Hanighen was coauthor of Merchants of Death, an expose of the role of the munitions industry in World War I, and as such the first book to oppose what became known as the Military-Industrial Complex. As you might suspect by now, Human Events newsletter was firmly in the anti-interventionist camp of Republican leader Robert Taft and the America First movement. It stood for the opposite of what the Republican Party and the conservative movement stands for now. Back then we routinely referred to the Democrats as “the War Party.” Sigh.

After graduating from Yale University, Stan served short stints at National Review and the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE), where he was introduced to the libertarian philosophy by the writer Frank Chodorov, and later took classes from economist Ludwig von Mises. Then Stan was recruited by Hanighen to be Managing Editor of Human Events. Chodorov had conceived the idea of the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI) and then promoted the idea of bringing young conservative/individualist student writers to Washington to work and study at Human Events. That’s where Bill Schulz, Doug Caddy, and I entered the picture.

Present at the Creation

Today’s Washington is filled with people who claim to be conservatives, even if they aren’t, but in 1957 there may have been 30 people in Washington who self-identified as conservatives, and we all knew each other. Human Events was Ground Zero in Washington conservative circles, and Stan Evans was our gatekeeper to that tiny but exciting world.

The two political traditions represented by that remnant were the Old Right-Taft Republican camp, and the anticommunist followers of Sen. Joe McCarthy. Most of us were of both persuasions. Bill Schulz was a student at Antioch College in Ohio, which followed a four-season academic schedule—three months of study, three months of work, repeated until you graduated or got tired of the routine. Bill worked writing columns and radio editorials for Fulton Lewis Jr., the Rush Limbaugh of his day, and that brought Bill to the attention of Human Events. Doug Caddy wrote for local conservative and McCarthyite periodicals while a high school student in New Orleans, and planned to attend Georgetown University in Washington. I was editor of my campus newspaper The Foghorn at Del Mar College in Corpus Christi, Texas, and my editorials caught the eye of Hanighen and Human Events publisher James L. Wick, an Ohio small-town newspaper man.

I claim bragging rights to being the very first Human Events/Stan Evans journalism student, since I was the first student contacted by publisher Wick. Schulz contests this claim, since he was the first one physically at the Human Events office thanks to his Antioch academic schedule. As you can imagine, this is a serious schism in First Class theology.

I wish I could remember my impression of Stan the very first time I met him, but I just remember that the four of us bonded immediately and thought of ourselves as a team, not as teacher and students. After all, we were 18 or 19 years old, and Stan was just four years older than us. Hanighen, Wick, and Chodorov were old fogies, and didn’t participate in our nightly beer and pizza excursions. We were on our own, and happily so.

Not that there were no differences of emphasis. Doug and I were Southern Democrats, a breed that no longer exists (among white folks at least), while Bill had been raised in Manhattan and Montclair, New Jersey, with a Republican upbringing. When Stan gave us our activist instructions, which he had got from his elders like Bill Buckley and Bill Rusher, Doug and I bristled. Why the Republican Party, for gawd’s sake? Stan explained that the Democratic Party was much too loosely organized at the grassroots level to be captured, while the Republican Party was organized like a country club that could be captured. We bowed to his expertise as a wise 22-year-old.

A few years ago I confronted Stan. “You know, Stan, at least two-thirds of your original journalism class has left the Republican Party in disgust. Does this suggest a failure on your part?” Stan put on that sardonic grin and voice he was famous for, and replied: “Maybe it’s a sign of just how well I taught you.”

When we first came to Washington, the Human Events offices were on K Street, N.W., but we soon moved to Capitol Hill—closer to “the action.” Days were taken up with writing and college classes, in different proportions, and one night a week Hanighen would have his generation of friends talk to us students—people like Chodorov and Freda Utley (mother of Jon Utley) and Chicago Tribune Washington correspondent Willard Edwards (father of Lee Edwards). Stan was a serious teacher when it came to style and accuracy, and I vividly remember his red-ink changes on my copy. (I have always said that my three best red-ink editors were Stan, Bill Buckley, and Neil McCaffrey, founder of Arlington House and the Conservative Book Club. Writing lost something important when the computer eliminated the red pen. Seeing all that red on your copy really caught your attention.) Stan’s most important advice, however, was: “The hardest part of writing is gluing your ass to the chair in front of the typewriter and actually starting to write.” I still have that problem 58 years later.

Life was never dull at Human Events. I remember the time an elderly woman dropped in at our office and complained to our receptionist—an older, sweet relative (aunt?) of Chuck Colson—how she had been abducted by aliens, they had implanted something in her head, and she was in constant pain. We were her last hope for help! The nonplussed receptionist came to Stan for assistance, and got it. Stan impulsively picked up some aluminum wrap (now where did he get that!) and soothed the woman. “Put this around your head as a hat,” he explained, “and it will block out the alien signals that are causing your pain.” She walked out a renewed and happy woman.

Under Stan’s tutelage we got our first tastes of direct political action. National Review’s Brent Bozell (the real Brent Bozell—pater) was running for some local office in suburban Maryland, and we joined in. The entire Washington conservative movement would gather on Brent’s side porch for instructions. And when Khrushchev became the first Soviet dictator to visit Washington, former Communist trainer Marvin Liebman came down from New York to instruct us on how to organize peaceful picket lines. (We were truly naïve about things like that. Nice boys and girls of the ‘50s didn’t picket.) We soon learned that picket lines in front of the White House were great social opportunities, particularly with some beautiful anticommunist coeds from Catholic girls’ colleges in Washington like Dunbarton and Trinity, and that only increased our activist fervor.

We had so little money, roommates were a necessity, and often a number of them. It was a very fluid situation. The New Left later had communes; we had flophouses. Stan used to love telling the story of how he returned from a weekend trip to find a stranger in his apartment living room. “Who are you?” he asked. The person gave his name and explained: “David Franke has left your apartment, and I have taken his place.” Out-of-towners would use Stan’s apartment as their home away from home. The Finn Twins (Charles and George) were rambunctious California veterans fighting the federal bureaucracy to start “The Flying Finn Twins Airline, Inc.” Whenever they were in Washington to press their case, they stayed, natch, at Stan’s Capitol Hill apartment. At one point Stan, myself, Robert Ritchie, and Harvey Fry became unlikely Washington civil rights pioneers when we rented a house in a then-black neighborhood of outer Capitol Hill.

We younger members of the Washington conservative community liked to meet at a historic Georgetown inn, Martin’s Tavern. The original Roosevelt brain trust used to meet in an extension of its main room called The Dugout, where they formulated their plans for the New Deal. We loved to flatter ourselves that we would be the new New Deal. Ah, hubris! In fact, that may be where Stan delivered his beer-soaked instructions on how we were going to destroy world communism.

A more frequent haunt (because it was cheaper) was Harrigan’s, a beer and pizza joint in Southeast Capitol Hill later leveled by urban renewal. That was the scene of perhaps our most hilarious escapade. For some reason Bill Rusher, the publisher of National Review, was in town and joined Stan and our journalism class for dinner than night. Now, those of you who had the privilege of knowing Rusher, will remember him as a formal type wearing three-piece suits, carrying an umbrella, and sporting a bowler hat—he really was born in the wrong country in the wrong period. But he was a great value to the conservative movement. Anyway, here we are having our proletarian pizza and guzzling cheap beers (you get the recurring theme here, right?), and our conversational level rose as the evening passed. Stan was extolling the virtues of this upstart new Senator Goldwater from Arizona, and a man at the next table took issue, leveling some expletives about our future leader. Stan demanded an apology, which wasn’t forthcoming, and then stood up, shouting: “That calls for a mouth punch!” Which he gave, and the two were grappling on the sawdust floor.

Luckily the proprietors broke up the fight before the police arrived, but fussbudget William A. Rusher was horrified—horrified, I tell you! You couldn’t convince him that this wasn’t Stan’s usual demeanor, or that the man deserved it for what he said about Barry. “That calls for a mouth punch” became Stan’s most famous saying until he announced, “I was always against Nixon—until Watergate.” As for Rusher, I think it was several years before he ventured back to the swamps of Washington, and then he took cabs straight from National Airport to the University Club and never left its doorman-guarded confines.

You can’t see me as I’m writing this, but I have both tears in my eyes and a grin on my face. Until we meet again, Stan.

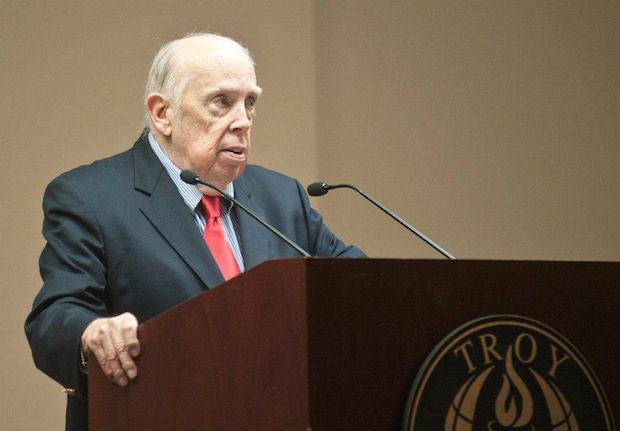

David Franke was one of the founders of the conservative movement in the 1950s and 1960s. He is the author of a dozen books, including Safe Places, The Torture Doctor, and America’s Right Turn.