Slavery Is Not Our Original Sin

You’ve probably heard it said that slavery is America’s “original sin.” Perhaps you’ve said it yourself. I know I have. In a sense, it’s plainly true. The bondage of millions of dark-skinned people—first Amerindians and then Africans—was a practice that was not only blessed by the American Constitution but one that, as The New York Times notes in their Pulitzer Prize-winning series on the legacy of slavery, the 1619 Project, predated the birth of the nation itself, stretching back to the first European settlements on the North American continent.

“The extremity of the violence was a symptom of the psychological mechanism necessary to absolve white Americans of their country’s original sin,” Nikole Hannah-Jones writes in the Project’s lead essay. Even in our highly secular age, we often still reach for religious language when we put our moral concerns into words. You don’t have to be a skeptic of climate science to notice how frequently environmentalists annex religious motifs to make points about the destruction of the natural world, talking about the earth as though it were a paradise despoiled by man, and prognosticating a coming apocalypse, complete with famines, flames, and boiling seas.

Not that there’s anything wrong with such talk. If the metaphor fits, use it. When one reads about the horrors endured by African-American slaves—from the Middle Passage to the forced separation of parents and children—it’s hard to think of a word more appropriate, more morally calibrated to the practice of slavery, than sin.

In another sense, though, it’s plainly not true. While slavery may have been one of the original sins committed by European colonists in North America, it was a sin that was neither original to European colonists nor to the continent of North America. Indeed, slavery is as old as civilization itself. Tallies of slaves have been found on clay tablets from the first human settlements in Mesopotamia. Slaves helped build both the pyramids and the Parthenon, tilled fields in Attica and paved the Appian Way. Homer tells us that Odysseus kept 30 male herdsmen and 50 female domestics in bondage, while Hammurabi, the sixth king of Babylon and author of the famous law code bearing his name, informed his subjects that though masters were not permitted to kill unruly slaves, they were permitted to lop off their ears.

Some of the greatest classical thinkers were slaveholders, among them Demosthenes, Plato, and Aristotle, the last of whom insisted that the practice would cease only when “each instrument could do its own work…as if a shuttle should weave of itself and a plectrum should do its own harp-playing.” In ancient Rome, roughly 30 percent of the population was held in bondage, about the same ratio as in the American Confederacy. In ancient Athens, the figure was closer to 45 percent.

Not everyone in the ancient world approved of slavery, of course, but nearly everyone accepted it. This included Jesus, who, according to the Gospels of both Matthew and Luke, decreed, “Blessed is the slave whom his master, returning, finds performing his charge.”

Modern Christians tie themselves in knots trying to explain away such pronouncements, picking translations that trade the word slave for servant or insisting that the former were treated no worse than the latter in Roman Judea—that is to say, not at all like their latter-day African counterparts. While there’s a grain of truth in this—manumission was, for instance, much more common in the Old World than the New—human bondage in ancient times could be every bit as barbaric as its 19th-century American equivalent. Just look at this account from the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, describing conditions in Mediterranean silver mines during the first century B.C.E.:

There they throng, all in chains, all kept at work continuously day and night…[T]hey wear lamps tied to their foreheads, and there, contorting their bodies to the contours of the rock, they throw their quarried fragments to the ground, toiling on and on without intermission under the pitiless overseer’s lash…No one could look on the squalor of these wretches, with not even a rag to cover their loins, without feeling compassion for their plight. They may be sick, or maimed, or aged, or weakly women, but there is no indulgence, no respite. All alike are kept at their labor by the lash, until, overcome by hardships, they die in their torments. Their misery is so great that they dread what is to come even more than the present, the punishments are so severe, and death is welcome as a thing more desirable than life.

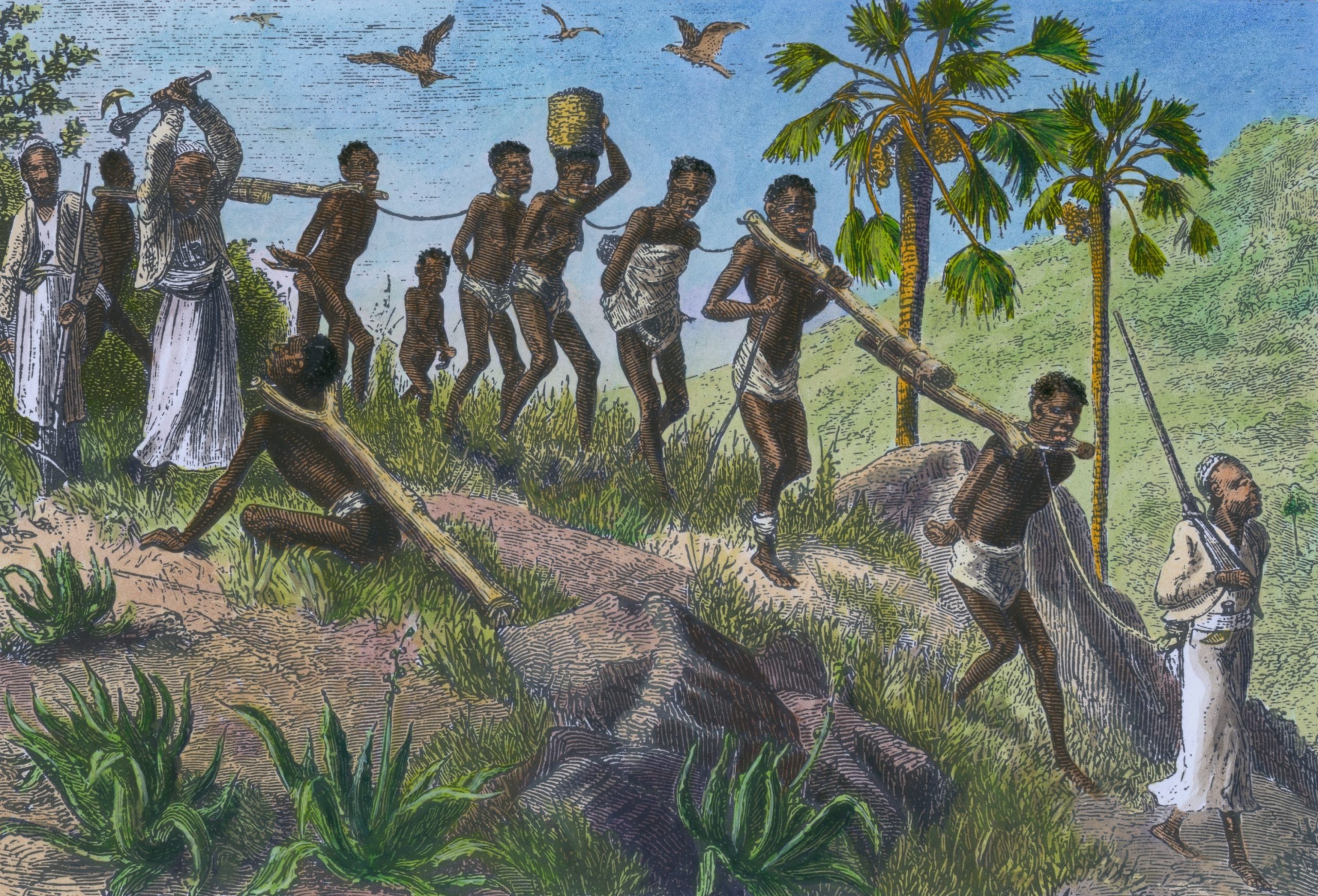

It is sometimes said that, though the practice of slavery goes back thousands of years, it was Europeans who first made it contingent on race, during the Age of Exploration. Not true. Arabs began trafficking in East African slaves as far back as 200 B.C.E., a practice that they would continue up until the dawn of the 20th century, shipping their captives all the way to Spain, India, and China.

Scholars estimate that, between the seventh century and the late 19th century, as many as 12 million Africans were kidnapped and taken to various regions of the Muslim world—roughly the same number who were transported to the Americas by Europeans.

Muslim corsairs, likewise, frequently took fair-skinned slaves as well, seizing upwards of a million western Europeans between 1500 and 1900. Until the 1640s, there were more British slaves in North Africa than there were African slaves in all the British colonies in the New World.

Why did Christians and Muslims enslave so many sub-Saharan Africans? Expediency, rather than bigotry, was the main cause. Racial justifications were dreamed up after the fact. Early on, it was Amerindians, not Africans, whom Europeans enslaved in the Americas. This, however, quickly proved unsustainable, as the Amerindian population was decimated by Old World germs. For a time, indentured servitude was tried, but this, too, was less than ideal, economically speaking. (Indentured servants, unlike slaves, had to be freed eventually and, like Amerindians before them, had a bad habit of dropping dead from disease, especially in the tropics.)

It was at this point that Europeans turned their attention towards Africa, and from a practical perspective, it’s easy to see why. The Europeans had plenty of goods (guns, textiles, intoxicating spirits) that Africans wanted, while the Africans had plenty of slaves that Europeans yearned for. We tend to forget today that almost all the Africans who were shipped to the Americas were enslaved not by Europeans but by other Africans. This was the reason that Arab traders had been coming to the continent since before the time of Christ: a massive slave market was already well established there.

It must be noted that slavery in Africa was very different from slavery in the New World. It was a system built on tribalism rather than racism. Slaves tended to be prisoners of war, unfortunates kidnapped by rival clans, or malefactors banished from their own villages. In many regions, African slaves were similar to medieval European serfs: their freedom was limited, their lives were committed to near-constant toil, but they maintained certain rights, among them the rights to marry, inherit goods, and own property (including other slaves).

This isn’t to say that slavery in Africa couldn’t be utterly dreadful, too. As in the Americas, the practice varied from place to place. Some slaves worked in mines, others on plantations run by brutal overseers, and others still were used for human sacrifice. All this made for easy pickings for foreign traders when they landed on African shores. Thanks to inter-tribal conflict, the continent was awash in slave labor. According to some estimates, at the height of the transatlantic slave trade, there were more slaves in West Africa alone than in all of the Americas combined.

But back to original sin. Though the term is derived from Christian theology—the original sin of man being the sin of Adam, eating from the tree of knowledge of good and evil—one needn’t be a practicing Christian to appreciate its use as a moral metaphor. Our vernacular is so littered with biblical expressions (an eye for an eye, by the skin of your teeth, fight the good fight) that we often forget that they emerged from the Good Book in the first place. They’ve effectively been leached of their theological flavor. This is not the case with original sin, at least not in the way that writers like Nikole Hannah-Jones use it. “I’m not optimistic about whether we will ever resolve our original sin,” Hannah-Jones explained in an interview promoting the 1619 Project. “Because how do you purge something that’s in your DNA?” Lest you think this was merely an offhand remark, here she is in the pages of the Project itself: “Anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country.”

Though her words are couched in the argot of science, their sense is distinctly religious. In Christian theology, Adam and Eve’s original sin did not die with them but was instead passed on to their descendants, marking every person (with the possible exception of Jesus and the Virgin Mary) born thereafter. Some might see this as excessive punishment for a relatively minor crime—i.e. the consumption of a single piece of fruit. But, at least according to the faithful, it was this sin that opened the door to all future sins, casting man out of paradise and making possible all the other hardships that followed. By the Times’s reckoning, slavery played a similar part in American society. “[Slavery] is sometimes referred to as the country’s original sin,” Times editor Jake Silverstein explained, after the series came out, “but it is more than that: It is the country’s very origin.”

Not that one can’t see how slavery and original sin connect. People have been pairing the two since at least the time of Saint Augustine, the fourth and fifth-century Christian philosopher. In Augustine’s case, however, he flipped the moral equation. He didn’t see slavery as man’s original sin; instead, he saw man’s original sin as a justification for slavery. Since all people were culpable for Adam’s crime, he reasoned, it only made sense that they endure the hardships of bondage, “imposed by the just sentence of God.” After all, wasn’t such hardship what differentiated our imperfect world from the better world to come?

This doesn’t mean that Augustine was an advocate of slavery per se. Indeed, he urged masters to treat their slaves as brothers in Christ. But he saw slavery as a cross that humans had to bear, something they had inherited from their forefathers, much the way we today talk about traits inherited through DNA.

The problem with original sin, both as a religious concept and metaphor for slavery, is that it robs individuals of moral agency, judging them en masse rather than by their own words and deeds. It condemns everyone alike, even newborn children, regardless of their actions, holding them accountable for crimes that they not only didn’t commit but, oftentimes, had no way of knowing about in the first place. The belief that one is answerable for the misdeeds of one’s ancestors goes back millennia. The Bible is full of admonitions against ancestral sin.

When the Israelites shirk their religious duties (as they so often do), God doesn’t just punish the offenders but often their children and grandchildren, as well. For centuries, advocates of slavery justified its practice by citing Noah’s curse of Ham in Genesis. The curse is, in fact, not of Ham—who made the mistake of seeing his father naked —but of Canaan, who made the mistake of being Ham’s son.

Such stories aren’t limited to the Abrahamic religions. The ancient Greeks told the tale of Oedipus, the mythical king of Thebes who killed his father and married his mother. As a result, the people of Thebes endured all manner of punishment (plagues, famines, the usual), despite having had no hand in Oedipus’s transgressions.

Much more consequential to human history is the ancestral sin attributed to the Jews: i.e. the killing of Jesus. According to the Gospel of Matthew, when the Roman governor, Pontius Pilate, hesitated to condemn the Nazarene, it was the crowd of Jewish onlookers who forced his hand, shouting, “His blood be on us, and on our children.” For 2,000 years that line, commonly known as “the blood curse,” has been used to justify countless crimes against Jews, from medieval pogroms to Hitler’s Final Solution.

It’s a sign of moral maturity that humanity has (albeit tardily) begun to discard such primitive precepts. When the articles of the Fourth Geneva Convention were drafted after the Holocaust, in 1949, “collective penalties” were explicitly condemned. “No protected person may be punished for an offense he or she has not personally committed,” Article 33 of the Convention states. It’s a shame that it took two world wars and the most horrid genocide in human history to drive this point home, but better late than never.

“A great step forward has been taken,” the International Red Cross declared. “Responsibility is personal and it will no longer be possible to inflict penalties on persons who have themselves not committed the acts complained of.”

In the months since the 1619 essays were published, a number of prominent historians have come forward to criticize the Project. James McPherson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Battle Cry of Freedom, argued that the series “lacked context and perspective on the complexity of slavery,” while Oxford historian Richard Carwardine was more blunt, calling it “a preposterous and one-dimensional reading of the American past.”

The line that probably came in for the most censure was Hannah-Jones’s contention that “one of the primary reasons the [American] colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Gordon Wood, an author of several books on the American Revolution and the early republic—and, like McPherson, a Pulitzer Prize laureate—dismissed this claim entirely. “The idea that the Revolution occurred as a means of protecting slavery—I just don’t think there is much evidence for it, and in fact the contrary is more true to what happened,” Wood explained. “The Revolution unleashed antislavery sentiments that led to the first abolition movements in the history of the world.”

Yet one doesn’t even have to dig that deep into the 1619 Project to find historiological hiccups. Look no further than the Project’s mission statement, which appears above the essays on the Times’s website, informing the reader that “the beginning of American slavery” can be traced back to “August of 1619, [when] a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the English colony of Virginia.” Strictly speaking, this is not the case. Slavery had been thriving in North, South, and Central America for millennia before Europeans arrived. It was practiced by the Incas, the Aztecs, the Mayans, the Iroquois, and the Cherokee, among many others. Slaves in these societies were often subject to atrocities that were just as appalling as those later endured by their African-American counterparts, as the historian Milton Meltzer makes clear in his description of bondage in the Pacific Northwest:

Once made a slave, a person could be bought and sold within a society or from one society to another. He was a chattel in every way, with no rights whatsoever. The master held the power of life and death over his slave. The slave might be killed on the death of his owner or crushed to death under the main post during a ceremonial house-building, or, as in the ritual of the Kwakiutl cannibals, eaten after being sacrificed.

But what if we read the Project’s mission statement a little less literally, putting aside Amerindian slavery—as Hannah-Jones and company surely intended—and focus instead on the enslavement of Africans in the United States? Unfortunately, this doesn’t improve matters. For nearly a century before the White Lion docked at Point Comfort in 1619, Spaniards had been carting black slaves to their colonies in Florida. In 1526, Lucas Vasquez de Ayllon started a settlement with 500 whites and 100 slaves. Hernando de Soto brought Cuban slaves along with him when he landed at Tampa Bay in 1539. And St. Augustine, Florida—the longest continuously inhabited European settlement in the contiguous United States —employed slave labor from the very day it was founded, in 1565.

So why all the fuss about 1619? Convenience undoubtedly played a part. When the Times decided to launch their series, a 400-year anniversary probably sounded a lot catchier than a 493-year anniversary. Nonetheless, it’s hard not to suspect that polemicism played a part, too. Modern American language, law, and government largely descend from the practices of British colonists, not Spanish conquistadors. If one wants show how the legacy of slavery still poisons American society, it’s best to begin at the root of that society, rather than the offshoot of another.

The irony is that the British colonies in North America were, in fact, some of the least dependent on slave labor in the New World. According to a recent estimate, of all the African slaves shipped to the Americas between 1500 and 1870, 48 percent were taken to the islands of the Caribbean; 41 percent to Brazil; 4.4 percent to Spanish settlements in South America; and roughly 5 to 6 percent to the British colonies in North America.

There were all sorts of reasons for this. Since sugarcane and cotton grow poorly in cold climates, northern colonies like Massachusetts and Connecticut didn’t have the same demand for workers that their contemporaries in the south did. Also, because the thirteen colonies offered an unusual amount of religious liberty for the period, they attracted a sizeable amount of free white labor. Ten times as many Europeans settled in British colonies as settled in French.

And, finally, although Anglo-American colonists were (obviously) not opposed to slavery on the whole, they’d already begun, by the 18th century, to develop what historian Seymour Drescher calls a “presumption of personal rights.” Though nominally still ruled by a king, ordinary, untitled Britons had a much greater say in the workings of their government than did their contemporaries in France, Holland, Spain, and Portugal.

“It was during the seventeenth century that the English tradition of invoking ‘ancient native liberties’ and ‘rights of the freeborn’ first became an important feature of the Anglo-American political landscape,” Robert J. Steinfeld writes in The Invention of Free Labor. “By century’s end, the ‘freeborn’ Englishman had triumphed so completely in language that he began to define for the English what was unique about their culture.”

In retrospect, it’s not at all remarkable that slavery once existed in the United States. As Drescher points out in his book Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery, “By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, slavery was established at every latitude in the Americas settled by Europeans.” What is genuinely remarkable is that at the height of the slave trade, while enormous profits were still being made, some states began to abolish the practice of their own accord.

First was Pennsylvania in 1780, then Massachusetts in 1783. Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island followed soon thereafter. New Jersey was next (in 1804) and then New York (in 1817). And that’s to say nothing of the measures taken to keep slavery out of new territories as they were acquired. The opposite is true, too, of course. Southerners like John C. Calhoun did their utmost to protect and preserve America’s slavocracy. But because the First Amendment protected free speech, and because the country had a thriving fourth estate, with a plethora of local presses, abolitionists were able to fight back. At the same time that Calhoun was spewing his bigoted bile, an escaped slave named Frederick Douglass was becoming a bestselling author and celebrity speaker.

These seeds of antislavery sentiment didn’t just spread across the United States; they spread across the globe. In 1788, the year that the U.S. Constitution was ratified, there was hardly a place on the planet, from Calcutta to the Congo, from the Amazon rainforest to the Arabian desert, where the trading of human flesh wasn’t accepted. But little more than a century later, it had been officially banned in a growing list of countries—not only the United States but in dozens of nations across the globe, from Mexico (1829) to India (1843), from Bulgaria (1879) to Brazil (1888). It was during this same period that Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Poland freed their serfs, as well.

A century may seem like a long time, and it is for a single person, but it’s barely a blink in human history. Yet within such a blink of time—roughly from the end of the 18th century to the end of the 19th century—an institution (slavery) that had spread virtually unchecked for more than 10,000 years was thrown into precipitate retreat all around the globe.

Not that slavery didn’t go down without a fight. (Just ask the Haitians who died fighting at Cap-Français or the Union troops who died at Cold Harbor.) In truth, it never really went down, at all. According to a recent estimate by the United Nations, there are roughly 40 million slaves in the world today. That’s more than three times the number taken during the entire 400 of the triangle trade. The difference is that today slavery hides in the shadows, whereas in centuries past it gamboled in the open air. The majority of modern slaves live under authoritarian political regimes, like the ones in Eritrea and North Korea, or in poor, developing nations, like Burundi and the Central African Republic. If this fact proves anything, it’s that Hannah-Jones isn’t entirely wrong when she says that slavery is part of our collective DNA. Her mistake is to assume that the our in that sentence refers only to Americans, whereas, in fact, it’s sewn into the DNA of everyone on the globe.

The main problem with the 1619 Project isn’t that it gets its history wrong—although, obviously, it does at times—but that it tries to implicate all of American history and culture in the sin of slavery. On occasion, this produces unintentionally comic effects.

In one piece, on how slavery infects modern capitalism, Matthew Desmond casts his gaze upon what he clearly considers to be a  modern abomination: Microsoft Excel. Some might wonder what’s so wrong with the app, other than its propensity for copy-and-paste errors. Desmond, though, sees the darker side of the software: double-entry bookkeeping. By using this accounting method, he explains, 21st century corporate executives “are repeating business procedures whose roots twist back to slave-labor camps.” True, but so is anyone who’s ever carried a wallet or signed a sales receipt. Doing so doesn’t make them aspiring slave owners.

modern abomination: Microsoft Excel. Some might wonder what’s so wrong with the app, other than its propensity for copy-and-paste errors. Desmond, though, sees the darker side of the software: double-entry bookkeeping. By using this accounting method, he explains, 21st century corporate executives “are repeating business procedures whose roots twist back to slave-labor camps.” True, but so is anyone who’s ever carried a wallet or signed a sales receipt. Doing so doesn’t make them aspiring slave owners.

Desmond’s Excel example, perhaps because it’s so silly, exposes the folly at the heart of the 1619 Project. Any modern phenomenon can be linked to slavery if you’re willing to work backwards from your conclusion. But that doesn’t mean the linkage is apt. As the essayist Adam Gopnik recently observed, “To live at all is to be implicated in the world’s cruelty.”

For this reason, it’s inevitable that the sins of our ancestors weigh on our minds: our lives, for better and worse, are contingent upon those sins. But contingency and responsibility are not the same thing. We are not responsible for our forebears’ sins, any more than our children will one day be responsible for ours. We are all born with a clean slate, morally speaking. Accepting that fact is part and parcel with accepting that we’re all created equal.

This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t try to right the wrongs of the past; we just shouldn’t blame ourselves for them. The best thing that we can do, both for ourselves and for future generations, is simply to try to improve the planet we’ve been given, learning from past mistakes, and reducing and rectifying our own sins, however original or unoriginal they may be.

Graham Daseler is a film editor and writer living in Los Angeles.