Robespierre And Auden, Autists

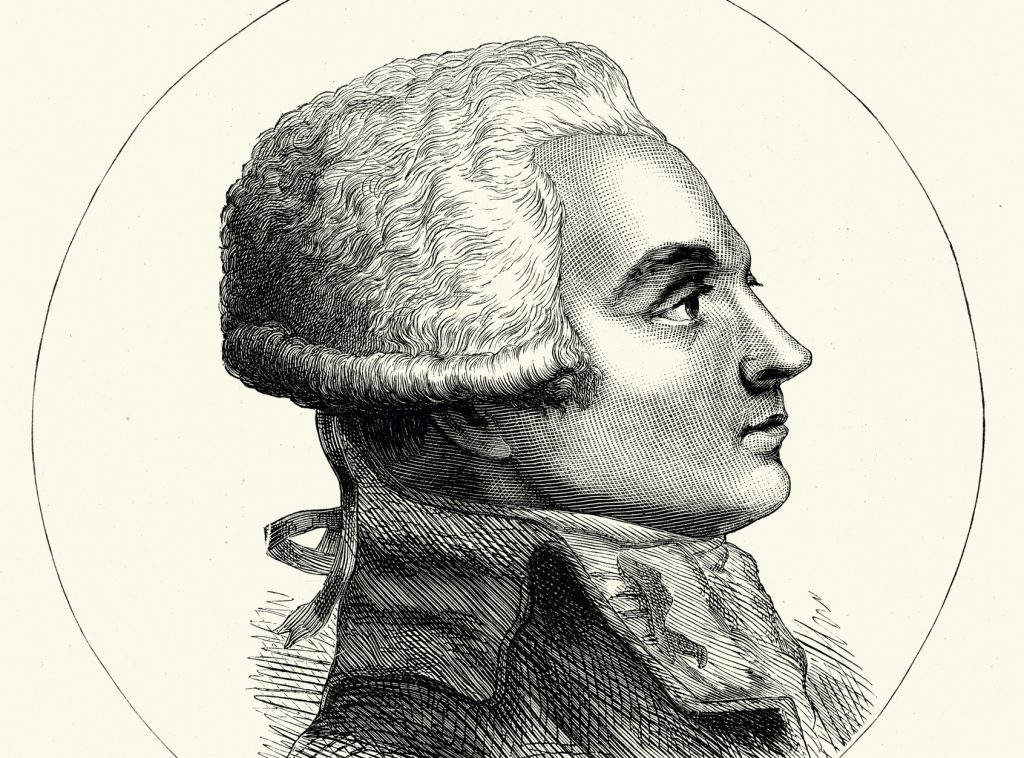

Some years ago, in Paris, my son and I read Christopher Hibbert’s history of the French Revolution. When we were done, we talked about how the book had inadvertently convinced us that Maximilien Robespierre was on the autism spectrum. (This, because both of us slightly are, and we recognized the signs.) I wrote this back in 2012 on this blog, but I’m re-upping it because the blog has many more readers today. (I also later read Ruth Scurr’s great book on Robespierre, Fatal Purity.)

We made our case that Robespierre was a high-functioning autist from what we know of Robespierre’s manner. All quotes below are taken from Hibbert’s book. For example:

1. Robespierre was extremely nervous and high strung.

2. He was very fastidious about his appearance.

3. “He rarely laughed, and when he did, the sound seemed forced from him, hollow and dry.” Some people who are more intensely on the spectrum do sound forced in their laughter, because they have trouble gauging emotion and its proper expression.

4. “He appeared to be unremittingly conscious of his own virtues.” This is key, because many spectrum folks are rather severe in their sense of order, and intolerant of anyone who doesn’t think and behave in what they consider to be the “correct” way.

5. “But if [young Robespierre] joined in [his sisters’] games, it was usually to tell them how they ought to be played.” Standard behavior. My late father, who was the coach of my Little League team, told me that he always felt so sorry for me as a player, because the game was nothing but a source of stress for me. He said that he could always tell that I had worked out in my mind, before every pitch, where the correct play would be, no matter where the ball would be hit. But I could not enjoy myself, because none of the other boys, being little kids who just wanted to have fun, would focus on the mechanics of the game, to my satisfaction.

6. “… and when they asked [young Robespierre] for one of his pet pigeons he refused to give it to them for fear that they might not look after it properly.” Again, standard behavior.

7. At university, “He seems to have been a solitary student who made no intimate friends and was apparently content to spend most of his time alone in the private room with which his scholarship provided him.” Spectrum folks tend to be loners.

8. According to his sister, the adult Robespierre “was almost completely uninterested in food, living mainly off of bread, fruit, and coffee.” Autists tend to eat simple diets, in part because of the predictability of a simple diet, and in part because sensory variety is unpleasant to them.

9. He would lose himself in his work, sometimes forgetting that there were other people around him, or what had been going on around him. Autists are characterized by their intense focus on their work, or whatever occupies their attention at a given moment. This, by the way, is one thing that my son and I share. Just the other day, my daughter stood next to me saying, “Dad. Dad!” five times before I heard her. I was laser-focused on a book I was reading. It’s kind of a super-power, but it also gets you into a world of trouble under certain conditions.

10. He was not a carnal man, nor was he interested in ordinary pleasures. Even when he was the most powerful man in France, he kept his same spare rented rooms in the rue Saint-Honore, and didn’t use his position to make his life more lively or comfortable. The work, and living by virtue, was the thing.

The called Robespierre “L’Incorruptible,” and I believe it. But I don’t think it was a matter of virtue, as people believed at the time, as much as it was neurological. He believed in a severe code of behavior, and followed it because that’s what made him feel at home in the world. He was incorruptible for the same reason that someone who has sensory processing disorder (a syndrome associated with autism) can’t wear a shirt with a tag in the back: it is extremely irritating.

The problem is that when Robespierre came into a position of supreme power, he tried to force all of France to do what he believed needed to be done. He saw the people as a problem to be solved. He saw governing as a game to be played strictly according to his rules. That did not work out well for all the people he sent to the guillotine. Eventually, he was made to join their number. He no doubt went to his death genuinely not understanding what he had done wrong.

Do I really need to say that I don’t believe people on the spectrum are all bloody-minded dictators in waiting? Yes, I probably do. In fact, people on the spectrum really do have gifts. I used to work for the philanthropy founded by the late Sir John Templeton, a legendary stock-picker. He died before I joined the foundation, but the more I talked to people who had known him, the more I picked up clues that the cheerful investor might have been on the spectrum. Once I visited his old office in the Bahamas. Someone who had been there with him told me that it was amazing to watch him work. They told me he would spread the stock pages out in front of him at his desk, and go into a kind of fugue state, deeply concentrating on the data. And then he would come out of it, and make his stock buys. This is how he became a billionaire.

I heard that and thought, “Of course! If he was on the spectrum, then he was able to perceive patterns in the stock data that nobody else could.” This, you might know, is how Michael Burry, the investor profiled in Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, became a billionaire. He saw stock market patterns leading up to the 2008 crash that nobody else could see.

There’s a blogsite called Autism-Advantage.com that talks about how autism really does help one think through certain problems. For example:

In an interview on MBUR, Michael Lewis commented about Michael Burry and Asperger’s Syndrome:

“ … it’s not an accident that these people are the ones who saw what the system failed to see and was blind to. They had qualities in them that enabled them to see. And in his case, it was a total resistance to the propaganda coming out of Wall Street coupled with an insistence on seeing what the numbers were.”

In reality, people on the spectrum are not seeing anything differently to what everyone else sees. Autists are not better at looking per se. But what they are better at is removing the obstacles that obstruct the view. The “unique insights” or “creative solutions” that are often cited in regards to autistic employees are often not much more than being able to see what’s staring us in the face, of being able to “cut through the crap” (excuse the French). When solutions are hard to find, even when they shouldn’t be, it can often be because we’re misled by “this is how we did it last time”, “we always do it like this” or “everyone feels that this is the best approach”. None of which cut any ice for an autist and none of which will necessarily help find a solution.

A Vancouver-based consultancy, Focus Professional Services, speak of their autistic consultants as having “unique ways of filtering information”. This goes to the heart of the autistic advantage: being able to eliminate unnecessary and confusing data by rejecting information noise.

If you’re searching for a needle in a haystack, the first thing you want to do is reduce the size of the haystack. And autists are very good at removing hay.

A reader wrote to me this week that I remind her of a roommate she once had, a woman who was on the spectrum. My correspondent said that her friend had a PhD in the hard sciences, and always had

this annoying habit of always darkly prognosticating about trends in society and science. I used to inwardly pooh-pooh her ideas about many things, or argue with her that her views were too dark. But, dang! She was nearly always right! The thing I realized is that she did not let her emotions cloud her judgment with a desire for things to be a certain way. I think this allowed her the ability to clearly see patterns in society that led her to crucial and unpopular but logical conclusions. It was as if she could just turn off her emotions with a switch — what a gift!

And yes, the friend had been diagnosed as on the spectrum. Anyway, the correspondent said she has wondered if this expresses itself in me with regard to seeing the logic of underlying patterns and forces in society and culture. I have thought that too — the extent to which my cultural pessimism is based on the perception of deep patterns in cultural life that elude most people’s vision.

Just yesterday, I mentioned to my wife that a friend of ours reacted badly when I sent the friend a news article about how an event in the friend’s city might be shut down in 2021. “How strange that she would react that way,” I said to my wife. My wife said that it’s not strange at all. “One thing that makes you good at your job,” my wife said, “is how you can separate your emotions from things you read. But most of us can’t do that. Most of us don’t find it easy to read bad news.”

Well, she has a point. My wife has always wondered how on earth I can lie in bed at night, read a history of the gulags, or the Holocaust, then turn the light off and go right to sleep. Come to think of it, that’s why so many people who only know me from my writing perceive me as much gloomier than I actually am in real life. I really can turn this stuff off. For me, doing this blog is like the old Warner Bros. cartoon about the sheepdog and the coyote, both clocking in to play their roles:

I’m not “playing a role” to be fake; I’m just saying that I can switch easily from the intensity of writing about the news, and decline-and-fall, to ordinary life. Cheerful life, believe it or not. It’s just business. Serious business, but just business. I am often surprised when others can’t do that. That’s a fault of empathy on my part — though when I do find empathy for someone, boy, does it ever take off like a rocket.

The weird thing is that I can focus like a laser on certain things, but others fall by the wayside, sometimes in big and consequential ways. I was once editor of a newspaper section. I can say with no false modesty that I was superb in finding essays to publish, and composing a balanced, interesting section, week after week. But I was terrible at doing the non-idea-related detail work necessary to be an editor — things like making sure writers got paid on time. Eventually I had to step down. Thinking back on it, whatever very mild autism I have made me exceptionally good at finding unusually interesting essays and editing them for publication. But it also made me a disaster at the important managerial work that needed doing for the section to function. I genuinely could not focus on that stuff; I was thinking constantly about the Big Ideas.

I was like this in college. My grades were not great. Maybe I graduated with a 3.2 GPA. Straight As in history, English, humanities; abysmal grades in math and science. I don’t actually believe I was as bad as all that in math and science. I believe that I could not bring myself to hold the focus I needed to do to succeed. I don’t know where the line was between laziness (a moral fault) and neurological incapacity. I used to think it was 100 laziness, but having learned more about the autism phenomenon through my family’s experience with it, I think the explanation is more complicated.

My desk, and my bedroom, have always been a huge mess. At some point my wife gave up on me. If you go into our bedroom now, it looks like Goofus and Gallant share a bed. Her side of the room is neat and clean. My side, full of books and papers stacked everywhere. I read the other day in a Clive James essay that W.H. Auden, who wrote the most crystalline, well-constructed poetry, was a world-class slob. I mean, off the charts messy. Just now, as I was writing this blog entry, I thought, “I bet he was on the spectrum.” Lo, I did a bit of online research, and indeed Auden diagnosed himself as on the spectrum. Not surprised. Not surprised at all.

Well, sorry for that digression. Because of my own, and my own family’s, experience with neuro-atypicality, I am fascinated by the way this phenomenon manifests itself in different lives and contexts. Robespierre is obviously a great outlier. Still, it’s fascinating to think about how the arc of his extremely consequential life might have been shaped by autism. Robespierre started out as a provincial lawyer who fought for justice for the poor. He was, no kidding, a social justice warrior — and I mean that in a complimentary sense. Can you imagine the courage it must have taken to fight for the poor under the French monarchy at the time? Well, Robespierre did. He hated injustice. Couldn’t live with it.

And then, years later, when he had become the most powerful man in France, his white-hot passion for justice, untempered by mercy and the capacity for empathy, became extreme cruelty.

It is easy to discriminate against autists, even those with high-functioning autism. They can be difficult to deal with. But they often have real gifts — somewhat unique gifts — that can serve the community if they are allowed to flourish. What they need (and I’m talking here about myself, though again, I’m probably not diagnosable) is the freedom to do what they’re good at, but also the limitations to keep them from attempting what they’re not suited for. You need Mr. Spock on the bridge of the Enterprise, but you don’t really want Spock to be the captain.

UPDATE: Auden once wrote:

Between the ages of six and twelve I spent a great many of my waking hours in the fabrication of a private secondary sacred world, the basic elements of which were (a) a limestone landscape mainly derived from the Pennine Moors in the North of England, and (b) an industry — lead mining.

It is no doubt psychologically significant that my sacred world was autistic, that is to say, I had no wish to share it with others nor could I have done so. However, though constructed for and inhabited by myself alone, I needed the help of others, my parents in particular, in collecting its materials; others had to procure for me the necessary textbooks on geology, machinery, maps, catalogues, guidebooks, and photographs, and, when occasion offered, to take me down real mines, tasks which they performed with unfailing patience and generosity.

From this activity, I learned certain principles which I was later to find applied to all artistic fabrication. Firstly, whatever other elements it may include, the initial impulse to create a secondary world is a feeling of awe aroused by encounters, in the primary world, with sacred beings or events. Though every work of art is a secondary world, such a world cannot be constructed ex nihilo, but is a selection and recombination of encounters of the primary world…

Secondly, in constructing my private world, I discovered that, though this was a game, that is to say, something I was free to do or not as I chose, not a necessity like eating or sleeping, no game can be played without rules. A secondary world must be as much a world of law as the primary. One may be free to decide what these laws shall be, but laws there must be.