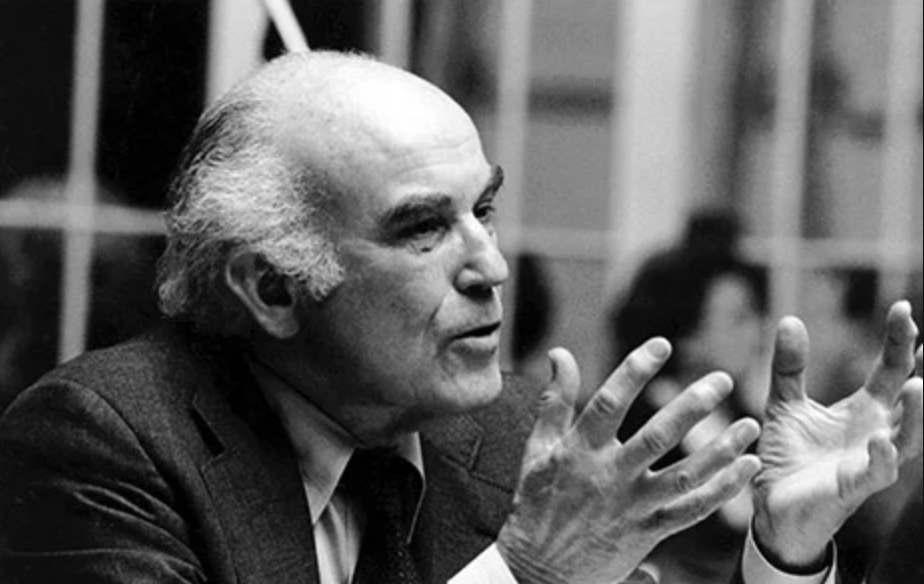

Robert Nisbet: TAC's Man

Nisbet’s political views consistently aligned with those animating The American Conservative.

Robert Nisbet must be the only man ever to have written for both Reason and Commentary, which is rather like James Dean being the only man ever to have slept with both Natalie Wood and Rock Hudson.

I like that ambidexterity—Nisbet’s, not Dean’s—but then I once cheerfully voted for Jesse Jackson and Ron Paul within a few months of each other.

Of all the pillars in the TAC pantheon, and they range from Robert Taft to Wendell Berry, from Christopher Lasch to Russell Kirk, from Pat Buchanan to Jane Jacobs, the late Robert Nisbet is the one whose political views most consistently align with those animating this magazine over its first two decades.

If anniversaries, even vicennial ones, are a time for looking back, then Nisbet’s Quest for Community, Twilight of Authority, The Present Age, and Conservatism: Dream and Reality ought to light our way.

Robert Nisbet grew up in a Christian Science household. I’m no follower of Mary Baker Eddy, yet I marvel at the quality of those raised Christian Scientist: Nisbet, Horton Foote, Robert Duvall, and the FDR-hating Ginger Rogers, among other great Americans. (We'll skip Nixon’s Cerberean guardians Haldeman and Ehrlichman.)

It’s that weird old America that I love and feel in my bones. I remember the day they knocked down the Christian Science church in Batavia. The Christian Scientists met in a once-grand columned manse built in 1812. It was razed because, our daily newspaper editorialized, it impeded “the rush into the future.”

To which we might quote Minor Threat, the greatest band ever to come out of Washington, D.C.: “Why is everybody in such a f—g rush?”

This question has been asked if not answered by Americans from Henry David Thoreau to Glenn Frey.

Sociologist Nisbet was a gentle contrarian, a Californian who had been much affected by his reading of the Southern Agrarian manifesto I'll Take My Stand while a student at Berkeley. Ah, Berkeley, hotbed of Southern agrarianism!

Nisbet had guts. When he delivered the National Endowment for the Humanities' Jefferson Lecture during the final year of the Reagan octennium, he arraigned Woodrow Wilson for imposing a “total state” on the U.S. during the First World War and trashing “the historic values of localism, regionalism, and decentralization.”

Those historic values, oft trampled by left, right, and center, offer the most practical and humane path out of our present mess. Their antithesis, assertive nationalism, weakens these smaller patriotisms, substituting fake community and, too often, bombast and belligerence.

Robert Nisbet spent part of his post-academic career at the American Enterprise Institute, which deserves credit for sheltering a man with his independent cast of mind. Imagine him in his office, ignoring the sounds outside, say, Michael Novak screaming at a research assistant, while Nisbet, who scorned what he called “briefcase veterans,” types such sentiments as:

- “War is the salvation of the state, just as it is the kinship community's nemesis.”

- “The family is the sworn enemy of the state.”

- “War and the military are, without question, among the very worst of the earth’s afflictions.”

Would that AEI’s Dick Cheney had absorbed this wisdom.

Late in life Nisbet consorted with libertarians. You’d never guess that from some of his earlier writings. He was attracted by the antimilitarist strain in libertarian thought, as well as its contempt for Big Brother. (Nisbet had written at length about Orwell’s 1984.) He was also appalled by the Moral Majority and elements of the early ’80s religious right, not because he advocated libertinism but because the New Right was blind to the inescapable enmity between militarism and family. It also rivaled TrumpWorld for scam artists per square inch.

To gauge the enfeebling of the American family, Nisbet proposed to examine trends in the intergenerational transfer of property rather than divorce rates. (He’d been divorced and maybe was sensitive about it. We all have our private embarrassments: I’m a sucker for gas-station cappuccino.)

War, the great scatterer, snaps generational ties. As John P. Marquand, novelist of the midcentury American upper-middle class, wrote in So Little Time, his 1943 requiem for pre-war America, “there was no use thinking any longer that someone who belonged to you might live in your house after you were through with it.”

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

I’d like to think that after we shuffle off this mortal coil the house of TAC will be filled with men and women we would recognize as our descendants, keeping lit the flame of home, family, and liberty, passing it on to those who come after.

Robert Nisbet loved to quote Edmund Burke that society is a partnership “between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are yet to be born.”

We are the link between Nisbet and the homemakers, peacemakers, and placemakers of tomorrow. Happy 20th.