Remembering Neville Marriner

Few conductors are loved. It could be as well, for music’s sake, that most conductors are loathed. Any impressive level of attendance at their obsequies readily calls to mind the witticism—attributed both to George Jessel and to Red Skelton—regarding the crowds at a universally abhorred Hollywood tycoon’s funeral: “Well, it proves what they always say. Give the people what they want, and they’ll come out for it.”

So how do we explain not merely the respect but the sincere affection that greeted the death, earlier this month, of the 92-year-old Neville Marriner (Sir Neville from 1985)? Mere British chauvinism cannot be a factor. After all, the obituary tributes on the radio networks of Paris, Rome, and Berlin (to say nothing of major American cities) appear to have been as kindly as anything broadcast or printed in London.

It cannot have been Marriner’s Guinness World Records achievement in having made more classical recordings—600 or so—than any other conductor, with the sole exception of Herbert von Karajan. No such sense of public bereavement marked Karajan’s 1989 demise. Nor can any particular media panache on Marriner’s part have been operating. He gave no more interviews than any other world-famous podium figure, and far fewer than most.

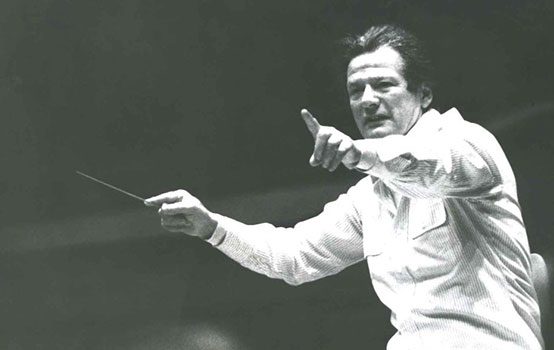

An instructive datum: one could have read every single issue of every single English-language music periodical during the 1960s and 70s—Marriner’s commercial apex—and still not have known, unless one had seen him in concert, what he looked like. Whereas Karajan’s aquiline profile and shock of white hair would have made him distinctive in any context, even if he had not possessed a particle of musical ability, Marriner’s bland visage might have belonged to any middle-ranking civil servant or any regional bank manager.

Doubtless the sheer length of Marriner’s performing life (he started as a violinist, joined a string quartet in 1948, and continued to conduct as recently as last September) helps to explain something of the personal loss which so many music-lovers clearly felt at the news that Marriner has gone. Something, but not, surely, all that much, amid a Britain that—despite the welcome absence of Tony Blair from 10 Downing Street—remains hopelessly in cultural thrall to youth-worship and, specifically, to Blairite drivel about “Cool Britannia.” No, there has to be some other reason for the voicing of genuine grief.

♦♦♦

It hardly needs saying that Marriner’s name will be associated for all time with his own chamber orchestra, the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, which he founded in 1958. (Anybody familiar with London knows that St. Martin in the Fields is an Anglican church on Trafalgar Square’s northeastern corner. As it happens, those buried there include Charles II’s orange-selling mistress-in-chief, Nell Gwynn. Yet one geographically challenged pundit—from San Francisco, be it stressed, not from Biloxi or Oshkosh—assumed from the group’s name that the Academy automatically performed outdoors. “In the fields?,” the pundit raged. “What kind of sadist is this Neville Marriner? Dragging those kids and their heavy instruments outside in that God-awful English weather …”)

Though one tends to assume that Marriner’s partnership with the Academy must have lasted almost as long as Elizabeth II’s with the Duke of Edinburgh, it actually endured for a surprisingly short time: 16 years. In 1974 Marriner handed over the formal leadership to Iona Brown, one of the group’s leading violinists, though he often enough appeared with the ensemble after that. (Asked in 1978 to explain the circumstances of her succession, Ms. Brown told British interviewer Geoffrey Crankshaw: “I did not apply. The orchestra asked me.”)

It was during those 16 years that Marriner established his reputation and raked up his liveliest sales, specializing in the 18th century, and reaching best-seller status when he, the Academy, and New-Zealand-born soloist Alan Loveday committed to disc—for Argo, a subsidiary of Decca—the first globally successful LP of The Four Seasons. There had of course been other recordings of Vivaldi’s quadripartite hit before, and there seem to have been approximately four billion of them since. Nevertheless, none had ever captured the public’s fancy like the Marriner / Loveday one. (Loveday, whom alcoholism later deprived of the sustained renown which should have been his, predeceased Marriner by only six months.) And no earlier Four Seasons recording, it needs to be said, had ever been so efficiently marketed.

Luck played an undeniable role in Marriner’s triumph. The ease with which so many long-forgotten LPs from mostly obscure sources can today be appreciated via outlets like YouTube confirms what any serious historian of classical recordings swiftly perceives: the crucial difference to careers, particularly during the Cold War, of being on a major label versus not being on a major label. (Likewise, it obviously helped to be in Western Europe rather than moldering behind the Iron Curtain.)

Marriner’s overall approach—felicitously described by American Record Guide editor Donald R. Vroon as “1960s baroque”, free alike from old-fashioned Otto-Klemperer-style heaviness and from the 1980s’ characteristic scratch-and-scrape frivolity—was not unique to him. It cropped up in the recordings of several other gifted conductors who emerged at much the same time: Fritz Werner, Günter Kehr and Jörg Faerber in (the former West) Germany; Claudio Scimone in Italy; Jean-François Paillard and Louis Auriacombe in France; Géry Lemaire in Belgium. Of these, Paillard alone achieved bestseller status (thanks to having scored a hit with the Pachelbel Canon, largely unheard before his 1968 recording, this recording having soared up the charts all over again when it adorned the Ordinary People soundtrack). Yet events confined Paillard mostly to the boutique Erato label, as they did Scimone. (Besides, major-label status did not prevent two other early-music specialists of Marriner’s generation—Raymond Leppard and Karl Richter—from incurring remarkably hostile critical coverage in Britain.) Whilst no-one is accusing Marriner of having been overrated, there can be no doubt that other maestri, lacking his influence in the UK’s artists-and-repertoire sector, were underrated.

In some ways, then, the world was waiting for someone like Marriner. As New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg noted, recollecting in tranquility the emotion generated by the long-playing record’s 1948 advent:

The baroque explosion was one phenomenon of early LP records. Baroque music demanded small forces, was relatively inexpensive to record, and all of a sudden everybody was into Vivaldi, Corelli, [Johann Friedrich] Fasch, [Tommaso] Albinoni, and dozens of names nobody had ever heard of.

Schonberg’s lack of enthusiasm for the results is obvious from the above. (Haydn’s chief biographer, H. C. Robbins Landon, grew so annoyed by the wholesale revival of not always thrilling baroque journeymen that he called one of his best-known magazine articles “A Pox on [Francesco] Manfredini.”) Umpteen record collectors disagreed. Many of us acquired our first phonographic experience of numerous works by Vivaldi (quite apart from The Four Seasons), Bach, Handel, Telemann, Haydn, and Mozart from exposure to Marriner’s Academy. Some of us retain a particular fondness for Marriner’s contribution to Pergolesi’s Magnificat, coupled with Vivaldi’s Gloria on a 1966 Argo collaboration starring King’s College Choir, Cambridge, and its usual conductor Sir David Willcocks.

Such a legacy makes all the more curious the shortage of permanent written material about Marriner’s doings. You would have thought that any musician of his celebrity would inspire book after book. Not so. The State Library of Victoria, on most subjects a commendably well-stocked institution, contains precisely one relevant volume: a 1981 guide, The Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, by two British journalists, Meirion and Susie Harries. Although a useful publication, this suffers from the disadvantages inevitable with the “authorized biography” format. High time for some ambitious young academic to redo the job with proper scholarly etiquette.

♦♦♦

In 1972, referring to the recent death of scholar-performer Thurston Dart, a critic for the (long-defunct) monthly magazine Records and Recording proclaimed that Dart’s mantle “had fallen on Neville Marriner and David Munrow.” The latter name will mean nothing to almost all readers under 50, but Munrow was an extraordinarily prolific broadcaster and recording artist who— usually with his Early Music Consort of London—produced more than two dozen LPs between 1966 and his suicide a decade later. (In photos the baby-faced Munrow bears a marked resemblance to his slightly younger and still shorter-lived contemporary, Marc Bolan, who enjoyed evanescent glam-rock fame with T. Rex.)

It goes to show Marriner’s star-power that during the 1970s, where exclusive recording contracts with particular companies were usually as inviolable as they had been 20 years before, Marriner managed to appear simultaneously on three labels: Argo, Philips, and EMI. Only Karajan showed similar skill in playing off rival recording executives against one another, and even he stuck with Deutsche Grammophon more often than not, especially in his old age.

♦♦♦

After the early 1980s the Academy found itself rendered unfashionable to a large extent by the whole original-instrument phenomenon. (“The period-instrument Taliban,” as it was surreptitiously known before the brilliant maverick musicologist Richard Taruskin demolished the movement’s unexamined artistic assumptions in his scathing 1995 polemic Text and Act, whereupon the movement’s critics grew bolder in the open.) Meanwhile Iona Brown, for all her formidable talents—notably a harder edge to her Vivaldi concerto recordings than Marriner had sought, and an eloquence in Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending at least as full-throated as Marriner’s—lacked her predecessor’s box-office allure. In any case, she had never enjoyed good health, and had been largely sidelined by arthritis and cancer well before she died in 2004.

Marriner himself continued to do admirable work both in concert and in the studio, by no means all of it (or even the best of it) with the Academy. He made Minneapolis and Stuttgart his chief non-London bases, but especially valuable were the Haydn Masses that he conducted in Dresden for EMI during the CD medium’s very earliest years. Even if Wagner’s and Bruckner’s epics would have been forever beyond Marriner’s reach, one must salute the excellence which he repeatedly managed when being cast against type.

With the Minnesota Orchestra in 1985 he supplied a roof-raising account of a showpiece that mercilessly separates the men from the boys: Respighi’s Pines of Rome, with its thunderous martial finale. (More predictable was his artistic success on disc with chamber-music Respighi: Ancient Airs and Dances and, especially, The Birds.) Or consider Marriner’s 1971 version, with the Academy, of that most desolate among Richard Strauss’s late masterpieces: Metamorphosen, for strings alone. Back-to-back comparison with Karajan’s pioneering 1947 performance reveals that any passages sounding rushed and lightweight occur with the Teuton, not with the Englishman. There is, accordingly, no legitimate reason to pigeon-hole Marriner’s executant persona.

A life, then, both long and well-lived; but Marriner’s repute involved something extra. As so frequently in this modern world, one finds oneself turning to Gilbert and Sullivan for clarification; and there, as so frequently in this modern world, clarification duly emerges. Cue H.M.S. Pinafore:

He is an Englishman!

For he might have been a Russian,

A French or Turk or Prussian,

Or perhaps Eye-tal-i-an:

But in spite of all temptations

To belong to other nations,

He remains an Englishman.

Let it be emphasized in the stylistic equivalent of 72-point upper-case type: an Englishman of the spittle-flecked, rancorous, soccer-hooligan-defending, Farage-idolizing, BoJo-indulging, Brexit-championing kind is precisely what Marriner was not, and could not be. A cosmopolitan he was. But a cosmopolitan devoid of merchant-banker sleaze. In his public deportment he always gave the impression of being, dare one even use the phrase now, “an English gentleman,” such as, in conducting terms, the world has not seen since the palmy days of Sir Thomas Beecham. There are probably no English gentlemen left in 2016 except the female English gentleman—if one may call her that—whose head adorns Britain’s coinage. Small wonder that Marriner’s passing has inspired so much genuine sorrow.

R.J. Stove lives in Melbourne.

Comments