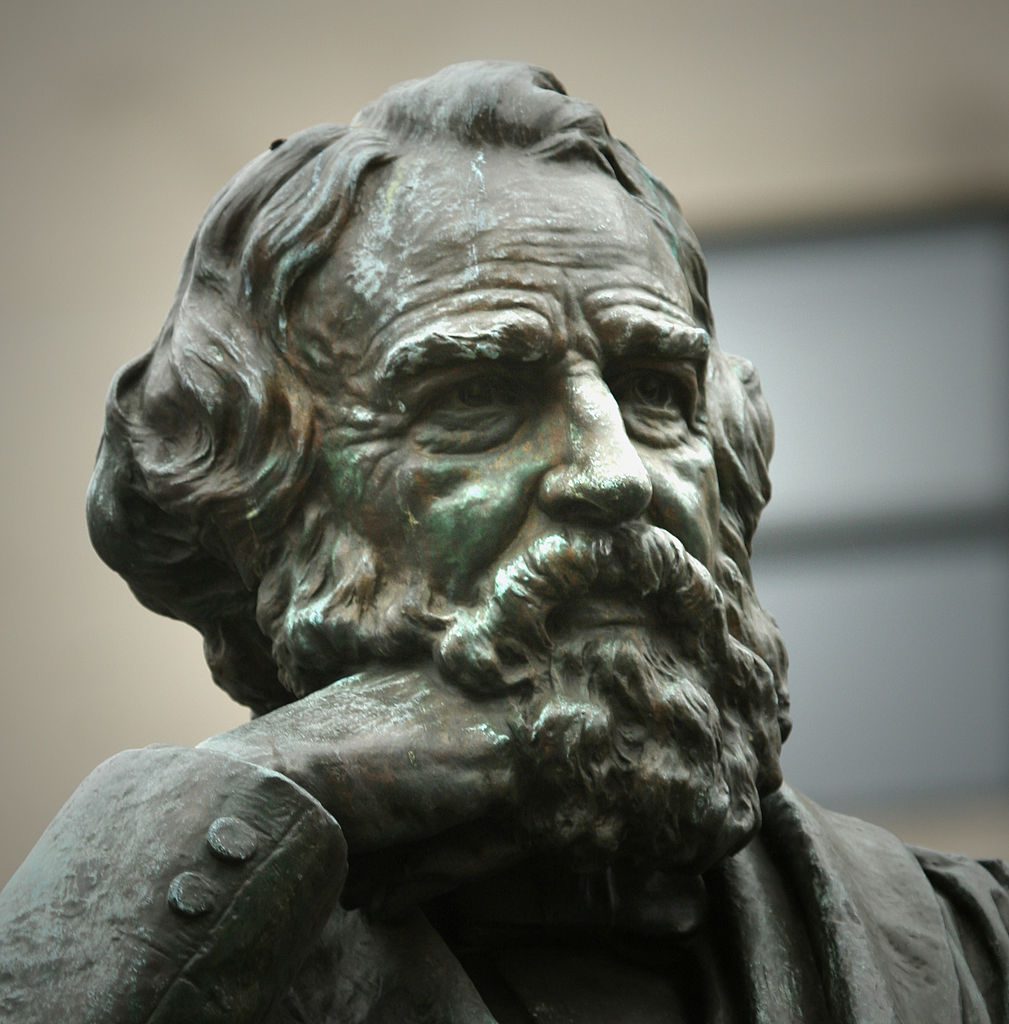

What Happened to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow?

In The New Yorker, James Marcus reviews Nicholas Basbanes’s new biography of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In his heyday, his fame rivaled the Queen of England:

On March 26, 1882, Ralph Waldo Emerson went to a funeral. As the elderly writer stared into the open casket, he grew perplexed. He could not identify the body. He seemed to know that the man had been a friend—indeed, he felt sad that the bearded stranger in the casket had predeceased him—but Emerson had no idea who he was. ‘Who is the sleeper?’ he finally asked his daughter. The answer was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Emerson was in the throes of dementia. Even so, the story seems like a small allegory of Longfellow’s disappearance from American culture. He was, in his heyday, the most famous poet in the English-speaking world. Perhaps T. S. Eliot, in his sports-arena-filling prime, would be a comparable figure. But Eliot was lionized by many people who didn’t read his poetry, whereas Longfellow’s books were devoured not only by the literati but by ordinary readers. When Longfellow was received by Queen Victoria, in 1868, she noticed the servants scuffling to get a glimpse of him. To her amazement, they all knew his poetry. No other visitor had provoked ‘so peculiar an interest,’ she noted. ‘Such poets wear a crown that is imperishable.’

Yet Longfellow’s fame proved to be more perishable than expected. How did he reach the summit, and what explains the century-old collapse of his literary reputation, which now shows some flickering signs of revival? Nicholas Basbanes tells the tale with diligence, affection, and an occasional note of special pleading in Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Knopf).

Basbanes alleges something nefarious in Longfellow’s sudden unpopularity, but Marcus doesn’t buy it: “Not surprisingly, it was the modernists who ejected Longfellow from the pantheon, viewing his metrical sleekness and front-parlor gentility as the worst kind of Victorian dross. The critic Van Wyck Brooks delivered the death blow in 1915. ‘Longfellow is to poetry,’ he declared, ‘what the barrel-organ is to music.’ Reputations rise and fall and rise again, and many writers retreat into a kind of hibernation when they die, waiting for the warmth of renewed acclaim to bring them back to life. Yet Basbanes seems to take Longfellow’s banishment rather personally. In fact, he alleges a hit job. Longfellow, he insists, ‘was the victim of an orchestrated dismissal that may well be unique in American literary history—widely revered in one century, methodically excommunicated from the ranks of the worthy in the next.’”

Rather, Marcus, who only read Longfellow after reading Basbanes’s biography—which makes Marcus an odd candidate for the task of evaluating Longfellow’s work—blames the poetry itself: “I snapped up the Library of America edition of Poems and Other Writings with a thrill of anticipation, fully hoping to encounter the Promethean figure of Basbanes’s biography. Reader, I tried. I thumbed through several hundred tissue-thin pages, added my wobbly midrash in mechanical pencil, chanted long passages aloud. I encountered the gems I have mentioned above, and many more. I was also won over by the sheer decency of the man, which seems somehow inextricable from his creations. As Oscar Wilde noted, perhaps with double-edged irony, ‘Longfellow was himself a beautiful poem, more beautiful than anything he ever wrote.’ Still, the vagaries of taste have performed their dismal magic. So much of his work seems dull, shopworn, generic. The Victorian music is there, sometimes gloriously, but just as often on the best toy piano you ever heard. It was Robert Lowell who characterized Longfellow as ‘Tennyson without gin.’ That’s about right—he is, except in his very best work, only mildly intoxicating, the equivalent of near beer.”

Thoughts? Is Marcus right? Or is Longfellow the sort of poet it takes time to digest and appreciate?

In other news: Dominic Green revisits the life and work of the jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker at 100: “As with John Keats, you wonder what Charlie Parker might have achieved had he really got going. Parker, who died in 1955, would have been 100 years old this year. The idea of Parker the centenarian is almost as preposterous as the idea that Parker would, on the occasions when both he and his alto turned up at a club at the same time, rewrite the vocabulary of American popular music, transform jazz into a modern art, become both famous and penniless, and die in the New York apartment of a jazz-fancying Hungarian baroness with the attending doctor, unaware that the corpse before him had combined the facility of Paganini with the harmonic intelligence of Beethoven, guessing that the deceased was 65 years old. He was in fact 35, and already immortal.”

P.J. O’Rourke reviews—well, maybe review is not the right word, but let’s use it anyway—Rachel Johnson’s Rake’s Progress: My Political Midlife Crisis: “Oh, to hell with the Olympian book review, that distanced and disinterested critique pronounced from on high. Our muses may dwell on a mountaintop, but we writers live on the molehill of our trade. An ant heap, actually, where every trifling insect in the little colony is kin. We’re constantly caressing each other with our feelers, trading morsels of wit with our mandibles and pushing each other under the passing shoes of the reading public. There’s no such thing as a book review without an agenda, any more than there’s such a thing as an ant that will leave your picnic lunch alone. My agenda here is to lavishly praise Rake’s Progress by Rachel Johnson.”

What happened to fiction in America? The line between journalism and fiction has become obscured, Robert McDowell writes in his quarterly column at The Hudson Review: “In the last few years of writing fiction chronicles for this quarterly, I’ve wandered into more than a hundred new collections of long and short fiction from all over the world, and just in that short time I’ve witnessed the lines blurring between novels and short stories, fiction and nonfiction. I’ve also noticed that laughter in fiction is practically dead. Everyone is so serious, even when attempting humor. In fiction, at least, it may be harder now than ever to be funny! The acceleration of this difference is almost dizzying. It’s not just the internet, or food, water, air, soil and weather pollution; it’s not just mass media sloppiness or downright dishonesty or political leaders who do nothing but run for reelection and lie, lie and lie some more; it’s not just the collapse of education, especially in the U.S. or the wispy qualifications of a new generation of musical chairs agents and editors in publishing. It’s all of these factors juiced together, and most certainly more.”

Working from home is here to stay, Matt S. Clancy writes in City Journal: “These trends suggest that it may be time to take another look at the ‘death of distance’—the notion, influential during the 1990s, that the Internet renders geographical location increasingly irrelevant. This idea lost traction during the 2000s, as it became obvious that the productivity benefits of cities were growing instead of declining. Innovation and other ‘knowledge’ work are collaborative phenomena, drawing on social dynamics that have benefited from physical proximity. As the value of knowledge work rose, so, too, did the importance of being near one’s current and potential collaborators; hence, we see the flourishing of big American cities like New York. But that development now seems to be flagging. While the share of Americans living in cities of more than 50,000 people has continued to rise—from 68 percent in 2000 to 71 percent in 2016—America’s largest cities (New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago) have started to lose population over the last few years. What’s driving the long-delayed emergence of remote work? Most obviously, the technology supporting it has improved. Perhaps equally important: we’re getting better at using the Internet, inventing new social and cultural methods of interacting on it. Comfort with working online is, unsurprisingly, strongest among the young. An Upwork survey found that 40 percent of 18- to 34-year-old small-business principals planned to hire full-time remote workers, compared with just 10 percent of principals aged 50 and older. Younger workers are also more likely to express interest in remote work. As Ozimek observes, even without further technological advances, remote work seems set to expand, simply for demographic reasons.”

Speaking of the Internet, L. M. Sacasas writes about how digital communities are replacing physical ones and what this means for politics: “The Internet is not simply a tool with which we do politics well or badly; it has created a new environment that yields a different set of assumptions, principles, and habits from those that ordered American politics in the pre-digital age. We are caught between two ages, as it were, and we are experiencing all of the attendant confusion, frustration, and exhaustion that such a liminal state involves. To borrow a line from the Marxist thinker Antonio Gramsci, ‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’ Although it’s not hard to see how the Internet, given its scope, ubiquity, and closeness to human life, radically reshapes human consciousness and social structures, that does not mean that the nature of that reshaping is altogether preordained or that it will unfold predictably and neatly.”

Photos: The works of Christo

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments