The Meaning of Harmony, Shakespeare’s Marriage, and the Best Bio of The Beatles

If you follow the critic Terry Teachout on Twitter, you already know that his wife, Hilary Teachout, died yesterday. “Loss is the price of love,” he writes. Sincere condolences, Mr. Teachout.

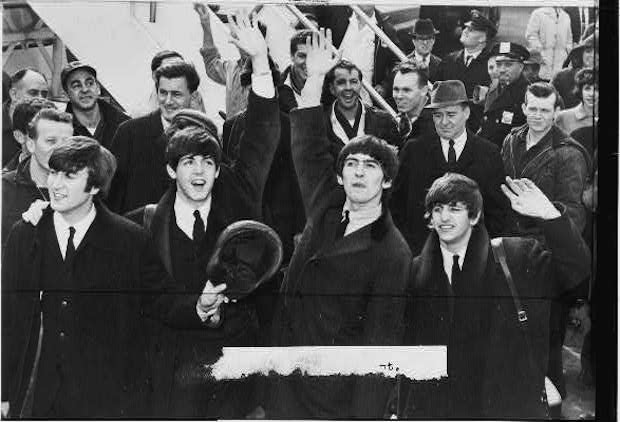

Dominic Green reviews “the best book anyone has written” about The Beatles, and there have been a few: “Explaining The Beatles is the West’s last act of theogony. All the episodes of the sacred biography are here, and most are devastated by Brown’s expert shuffling of perspectives. The heart of the Beatles mystery is exposed not through the usual catalogue of songwriting sessions and studio techniques, but through alternate histories, passing encounters and the biographies of the massed ranks of Fifth Beatles – the helpers, disciples, witnesses and nearly men whose memories are like apocryphal gospels. If a German raid had not compelled Jim McCartney and Mary Mohin to get to know each other better, would Paul McCartney have been born? If Paul had passed his Latin O level, he wouldn’t have stayed down a year, befriended George Harrison and introduced him to John Lennon. Would any of us be the same if Ringo had never emerged from a ten-week coma as a child, or if his grandmother hadn’t then forced him to write with his right hand instead of naturally with his left, which gave his drumming ‘the idiosyncratic style that countless Beatles tribute acts still find hard to duplicate’?”

More: “After Brian Epstein’s death from an overdose of sleeping pills in August 1967, they become easy prey for con artists: Magic Alex, the electrician who can’t wire a plug, the sinister Maharishi, the crooked Allen Klein. Yoko Ono first makes a play for Ringo, but he ‘couldn’t decipher a word she was saying, and exited as fast as his legs could carry him’, so she settles for John, the middle-class Beatle who wrote ‘Working-Class Hero’. Nothing is real. The worse it gets, the funnier it becomes. Paul and Ringo somehow keep their heads, Ringo taking baked beans to Rishikesh and Paul working up a passable impersonation of normality, but John and George blow their minds with LSD. John tries to convince Paul that they should both elevate their consciousnesses by having their skulls trepanned. ‘You have it done, and if it’s fine we’ll all have it done as well,” Paul says.’ Read the whole thing.

In other news: Instagram gives medieval art new life.

A spot-on portrayal of life as a jewelry hustler: “We were called hip-pocketers, because we lived from one deal to the next: Your business could fit in the wallet in your pocket. You bought a used Rolex at a pawnshop for a thousand bucks from the kid who’s just paid five hundred for it, hurried it over to your watch guy to hit it on the wheel and make it look new, replaced the old worn buckle with a South American counterfeit for fifty bucks, and resold it to your friend who owned the jewelry store a few blocks over for twenty-two hundred, twenty-two seventy-five if she wanted a counterfeit leather box. She could retail it the same day for thirty-five hundred . . . What I most loved about the movie Uncut Gems was how the directors Josh and Benny Safdie managed to capture the frenetic pace, the desperation of the hustle in motion, when you have too many balls in the air and one deal is leveraged against another. The whole shady thing might actually work if jeweler Howard Ratner, played by Adam Sandler in a ferocious performance, could just apply enough will, imagination, and sheer wild focused panic to the solution. But if one thing goes wrong—like, in the movie, when the celebrity basketball player won’t return a gem he has borrowed as quickly as he promised—it could, and naturally wants to, all come crashing down.”

Miranda France reviews a skillful but at times overwrought historical novel imagining Shakespeare’s courtship and marriage to Anne Hathaway: “He was eighteen when they married; she was twenty-six and pregnant with their first child, Susanna. Twins Judith and Hamnet followed, and at the heart of this story is Hamnet’s death from the plague at the age of eleven.”

Essay of the Day:

In First Things, John Ahern writes about the meaning of harmony:

“Around the start of the seventeenth century, a new sense of the word ‘harmony’ emerged. To that point, harmony in music had been produced by the pleasing opposition of two melodies according to the principles of counterpoint. In the 1600s, ‘harmony’ began to denote the non-melodic accompaniment to a line of melody. This sense remains colloquial today. If I say, ‘Here is a melody, let’s add some harmony,’ I mean that there is a tune and it is getting some additional, subordinate music to accompany it. It is basically synonymous with chords. We would describe Taylor Swift as the melody, and her back-up band—its guitars and piano and bass—as the harmony.

“But what is ‘harmony’ in the older sense of the word, captured particularly in Bach’s counterpoint? Counterpoint is the accumulation of multiple melodies. It is like Louis Armstrong playing an improvised tune on his trumpet at the same time as Ella Fitzgerald sings ‘La Vie en Rose’—two different melodies simultaneously. Neither is subordinate to the other, or, if there is subordination (perhaps we listen a little more to Ella’s voice than the trumpet), they are both melodies, a status that the piano, plunking out chords in the background, does not share. In true counterpoint, all the sound created is produced by people singing or playing melodies. If we lived several hundred years ago, we would say that ‘harmony’ is what joins and holds together those melodies, their counterpoint, in a pleasing fashion.

“And though this older sense of ‘harmony’ is no longer dominant, idiomatic English retains it alongside the modern sense. If I were to say, for instance, ‘In marriage, the husband plays the melody and the wife plays the harmony,’ I would be expressing both a bad view of marriage and a modern view of harmony. Harmony here is a discrete entity supporting the melody, existing beneath and for it. But if I said, ‘The husband and wife, though they disagreed, finished the conversation in harmony,’ I am using ‘harmony’ in a different, but recognizable, sense. It is no longer a distinct line, no longer a role one of the two parties plays; it is instead a relation between the two, both of whom are human subjects existing in the same plane.

“Very often, ‘harmony’ serves as a synonym for perfect agreement: A harmonious marriage or society is one in which all members are in perfect accord. But the contrapuntal idea of harmony implies a different vision of social concord, one in which the various parts retain autonomy but find their fullness in relation to each other and to a certain order that arises from their life in common. ’Implicit in the term contrapuntal,’ says Walter Piston, ‘is the idea of disagreement. The interplay of agreement and disagreement between the various factors of the musical texture constitutes the contrapuntal element in music.’ This account mirrors the almost mystical formulation of Franchino Gaffurio, the fifteenth-century music theorist, for whom harmony could be defined as discordia concors, ‘agreeing disagreement’ or ‘concordant discord.’ Contrapuntal harmony is an almost miraculous occurrence, a sonic solution to the problem of the one and the many.”

Photo: Trakai Island Castle

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments