In Defense of Gentrification, Vegans Becoming Butchers, and Sparta Reconsidered

I have been ambivalent about Trump’s proposed tariffs . . . until now. It seems that the price of Gruyère may go up by 100% if tariffs against the EU are put into place. Let’s hope that doesn’t include Gruyère from Switzerland—that is, the real Gruyère that everyone loves, not the holey French stuff. Switzerland isn’t part of the EU and buys plenty of Boeing jets. It should in no way be punished.

In other food news, these vegetarians became butchers after they started eating meat from grass-fed animals and saw their health improve: “‘As soon as I started eating meat, my health improved,’ she said. ‘My mental acuity stepped up, I lost weight, my acne cleared up, my hair got better. I felt like a fog lifted.’ All of the meat was from healthy, grass-fed animals reared on the farms where she worked. Other former vegetarians reported that they, too, felt better after introducing grass-fed meat into their diets: Ms. Kavanaugh said eating meat again helped with her depression. Mr. Applestone said he felt far more energetic . . . Grass-fed and -finished meat has been shown to be more healthful to humans than that from animals fed on soy and corn, containing higher levels of omega-3 fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid, beta carotene and other nutrients. Cows that are fed predominantly grass and forage also have better health themselves, requiring less use of antibiotics. ‘There’s one health for animals and humans,’ Ms. Fernald said. ‘You can’t be healthy unless the animals you eat are healthy.’”

The example of Rome: “At various points in American history, various reasons have been advanced to explain why the United States is bound to join the Roman Empire in oblivion.” The problem is, Tom Holland writes, America is not Rome: “History serves as only the blindest and most stumbling guide to the future. America is not Rome. Donald Trump is not Commodus. There is nothing written into the DNA of a superpower that says that it must inevitably decline and fall. This is not an argument for complacency; it is an argument against despair. Americans have been worrying about the future of their republic for centuries now. There is every prospect that they will be worrying about it for centuries more.”

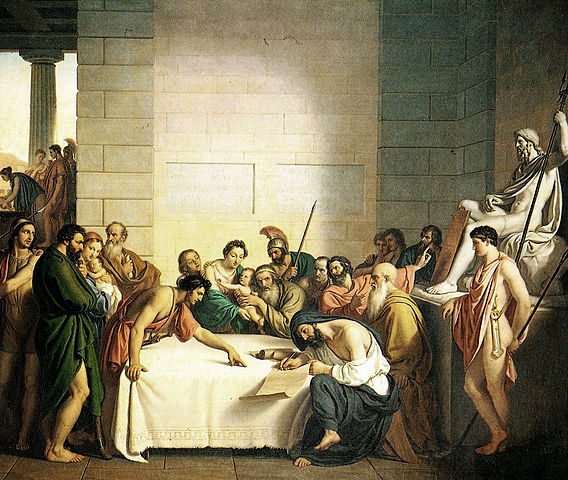

Also from the ancient civilization desk, there’s this defense of Sparta from Nick Burns: “These latter-day laconophiles (lovers of Sparta, that is) tend to exalt the cruellest, grittiest, and most violent aspects of Spartan life. They make virtues of the brutal training regimen forced upon young Spartans, of the city’s merciless repression of its surrounding population, of its anti-intellectual and hyper-martial mores. It’s also true that we can find in Sparta’s history starker versions of the darker tendencies of our own society: militarism, intolerance of outsiders, indifference toward the value of human life. At the same time, today’s laconophiles overlook characteristics of Spartan society that many of them would object to, including relative economic equality, cultural egalitarianism, and military restraint.”

Quoting Plutarch, Burns argues (or seems to argue) that “in Sparta, those who were free—that is, the citizens—were freer than people anywhere else in the world” and cites Benjamin Constant’s distinction between individual and communal freedom: “Ancient liberty . . . was unabashedly majoritarian. It was not individual but communal. To be free in an ancient sense was to participate in the life of the city on equal terms with others, and have a say in public debates on domestic and foreign affairs, the results of which would bind everyone. This Spartan kind of freedom was active, not passive. It made no promises about religious freedom. It had no concept of a private sphere of rights—but it was freedom nonetheless.”

It was a kind of freedom, no doubt, but characterizing Sparta as a great example of “communal” freedom (again, if that’s what Burns is saying here) is a bit of stretch. Sparta simply elevated one kind of community (the city) above all others (particularly the family), unlike Athens, which left the family largely untouched and tried to maintain a more complex relationship between the two.

But I agree with Burns’s kicker: “Something in human nature craves more than a sphere of rights, more than promises of nice things and free association. One need neither equate nor endorse the rise of democratic socialism on the left and of nationalism on the right to observe that each demonstrates, once again, that people crave more than individual liberty, full stop.” Give the whole thing a read and decide what you think for yourself.

Planning on going to the Louvre on your next trip to Paris? You will likely need a reservation.

Toni Morrison has died. She was 88.

Does gentrification hurt low-income residents in a neighborhood? A new study says no. Gentrification’s status “as a great urban evil, a ravager of lives and destroyer of communities, is based as much on faith as on fact. Most scholarly research on the topic compares snapshots of cities and neighborhoods at different times but loses track of what happens to the actual people who live there. Now, a pair of studies has used Census micro-data and Medicaid records to track specific residents of both gentrifying and non-gentrifying neighborhoods — where they live, where their children go to school, when they move, and where they go. The researchers come up with some startling findings. In a paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Quentin Brummet and Davin Reed say that urbanites move all the time, for countless reasons, and that gentrification has scant impact on that constant flow. Those who stay put as a neighborhood grows more affluent often see their quality of life rise and their children enjoy more opportunities. Those who leave rarely do worse.”

Essay of the Day:

In Standpoint, Patrick Heren writes about hitchhiking from Laredo to New York in 1980. He contracted polio when he was three and has walked with crutches ever since:

“My parents sensibly decided that I should approach life as if I were entirely able-bodied, sending me to school with able-bodied children and generally expecting me to be self-reliant. There was a certain doublethink involved, of course: I regarded myself as a tough guy who could take care of himself and join in the sorts of activities my friends enjoyed, despite the fact that my participation was necessarily restricted: when playing soldiers I could be a sniper, or man a machine-gun nest, while in football I would play in goal.

“Psychologically this was reasonably effective, and at university I was flattered when friends—especially girls—said they did not think of me as disabled. It also led to a certain lack of realism on my part, culminating in a frankly insane US road trip in the summer of 1980.”

Photo: Lavender

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments