Power to the People?

Reaganland: America’s Right Turn, 1976-1980, Rick Perlstein, Simon & Schuster, 1,120 pages

The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, Thomas Frank, Metropolitan, 320 pages

The Stakes: America at the Point of No Return, Michael Anton, Regnery, 407 pages

Rick Perlstein has a rendering of history.

“It was part of a strategy to signal that Republicans intended to seriously contest the South for the first time in over a century,” he writes. “[Ronald] Reagan was fetched at the airport in Meridian by his state chairman, Congressman Trent Lott. Lott had been president of the fraternity that stockpiled a cache of weapons used to riot against the federal marshals protecting a black student seeking to enter the University of Mississippi.” Perlstein reports that it was Lott who urged the president: “If Reagan really wanted to win this crowd over, he need only fold a certain two-word phrase into his speech: states’ rights.”

Perlstein was once dismissively dubbed the “gonzo historian” by former New York Times book review editor and rival chronicler of conservatives Sam Tanenhaus. Indeed, Perlstein recalls the notorious Neshoba County Fair “states’ rights” speech and countless other anecdotes in his 1,100-page opus, Reaganland, in downright Thompsonian fashion. It is his fourth installment of mid-century, American conservative history and it is his best, besting the magisterial Nixonland. Perlstein, a hard lefty journo, might indeed take himself too seriously, but at least he usually affords the same treatment to the subjects of his histories.

Rather than a conventional denunciation of the medial event in Reagan’s use of “the Southern Strategy,” Perlstein actually does reporting. Perlstein reveals Reagan didn’t really believe in what he was saying. “The way he carried out Trent Lott’s suggestion doused the enthusiasm of a previously energetic crowd,” Perlstein says. “And it was hardly worth it. The backlash was immediate and caustic.”

But what did Reagan actually say? “I still believe the answer to any problem lies with the people,” Reagan told the crowd. “I believe in people doing as much as they can for themselves at the community level and at the private level, and I believe we’ve distorted the balance of our government today by giving powers that were never intended in the Constitution to that federal establishment.” And Reagan said: “I believe in states’ rights.” It was considered by his critics as tantamount to Morse code to white supremacists. Perlstein dresses up the story pages before with paragraphs of dispatches on the dominance of racial vigilantism in the region in the years before Reagan’s speech.

But after his address, in the inferno of an August afternoon in central Mississippi, Reagan won. Though reasonable points about black voter suppression can be raised, in November, Reagan won Neshoba County, he won Mississippi, and he won the United States Electoral College. And he did so against a Deep Southern, Democratic incumbent president, which was previously unthinkable. And the GOP hasn’t relinquished Mississippi since—not even when neighboring Arkansan Bill Clinton and Tennessean Al Gore dominated the Nineties.

Perlstein’s chronicle is about the 40th president but, of course, can’t escape the shadow of the 45th. Perlstein has called Donald Trump an heir to Reagan, only stripped of the sunny optimism. A generation of global leaders, usually liberal, championed democracy, only to see Palestine elect Hamas, Egypt elect the Muslim Brotherhood, Mississippi go to Reagan, Britain secede from Europe, and America annoit Trump.

So, snapshots like Perlstein’s belie the perhaps central anxious question of the age: Are the people always right?

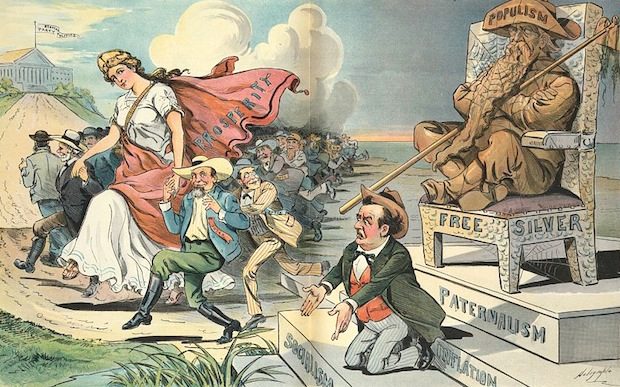

Perlstein’s friend Thomas Frank is hopeful. He thoroughly rejects Trumpism but is not uniformly unsympathetic to the elements of its success. He likes populism (correctly applied, of course). He’s comfortable that there are clear interests of the people and against the elites. “What makes populism truly dangerous, our modern-day anti-populist experts concur, is that it refuses to acknowledge the hierarchy of meritocratic achievement,” Frank writes in The People, No, his 11th book and a successor to his What’s the Matter with Kansas?, released the last time a Republican president ran for re-election, and which made Frank famous. Populism “in its deep regard for the wisdom of the common person…rejects more qualified leaders,” Frank explains, “which is to say, it rejects them, the expert class.” Only Frank says that Trump, like Reagan, is an imposter—that is, a fake populist qua fake populism, the kind perfected by Republicans over the last half-century.

Anything Frank writes is worth picking up. In particular, few others besides perhaps former TAC editor and William McKinley biographer Robert Merry write history on the early 20th century with such apparent passion. Frank’s volume is long on description and short on prescription—probably right for a journalist. But the author also writes bitter paragraphs like this: “In this moment of maximum populist possibility, our commentariat proceeds as though the true populist alternative is simply invisible or impossible. You can either have meritocracy or you can have Trumpism. Those are the choices, the punditburo proclaims. … Between them there is no middle ground and no possible alternative.” Frank harkens back to the original Progressive era and, in particular, he venerates the New Deal as a model for the future. But he also leaves the reader with the impression that the only problem with populism today, like the old line about communism, is that true populism has not yet been tried.

Michael Anton thinks true populism has been tried, though it’s still in its birthing stage. Previewing his latest in the Claremont Review of Books, the former senior White House official talks down naysaying of the current president: “If I have any criticisms of President Trump, my answer is always the same: there’s little wrong with President Trump that more Trump couldn’t solve. More populism.” Like Frank, Anton has a similarly clear understanding of the political battlefield, though the two wildly disagree where the lines are drawn. Anton was the author during last general election of the infamous “Flight 93 Election” essay, and he returns with The Stakes. He presents a country in permanent revolution. For Anton, “the people” are clear: decent, middle Americans against an elite flirting with treason.

Frank and Perlstein see the federal government as generally a force for good. But Anton is the only one of the trio to have served in the beast. While happy to fight free-market happy talkers of an earlier generation, Anton is the most skeptical of too much power amassed in Washington—or anywhere, it seems, from the corporate boardroom to California. Recently, he attracted considerable controversy by warning of a potential Democratic coup in 2020. Like many in the Trump moment—from former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, to current White House senior counselor Stephen Miller, to Tucker Carlson, to the late Andrew Breitbart and his successor, Alex Marlow—Anton is from the California diaspora.

Anton sees Golden State politics coming to a theater near you—without the nice weather. “What California cannot accomplish through regulation and two-track enforcement,” Anton warns, “it attempts to impose via stultifying conformity, backed up by public humiliation and ostracism for those who don’t fall in line.” Anton once hailed the country’s most beautiful state as a mecca for the common man: “It was cheap, safe, clean. It had space,” he told Politico while in the White House. “It couldn’t last.” Today, that putative, great encyclopedia for the common man, Wikipedia (whose first servers were housed in California) labels Anton as a figure with a “conspiracy-theory orientation,” a likely consequence of his recent “coup” talk.

The Trump years have seen conservative revolt against California and tech, a stunning turnaround from a generation ago when the gold coast was seemingly almost technolibertarian in orientation. But in 2016, the right used the tools created by mostly liberals to storm Washington. In the years since, the large technology firms have mostly concluded that the concern over the specter of hate speech outweighs the merits of total democracy in cyberspace. Perlstein writes on the 1976-1980 period, the years of the center-left Carter presidency, but nonetheless labels it “America’s right turn.” One wonders if a future historian will soon write a “left turn” history of the years 2016-2020. The atmosphere in America’s most innovative sector certainly implies a trajectory.

All three authors look back more than they look forward. As America hunkers down for a potentially hellacious winter, reflection on how we got here is certainly in order. Anton sees a point of “no return.” It allows him to wave off populist objections to Trump’s rule: that the president hasn’t exited foreign theaters, that he’s governed too conventionally economically, and that he sees the stock market as his scorecard. Others see an older, more inchoate history here. “If you just noticed that voters threw the bums out in 2006, 2008, 2010, 2014, 2016, 2018, and now likely 2020, maybe you’d realize that ads and the jibberings of DC elites don’t matter to voters,” liberal activist Matthew Stoller wrote this year of recent federal elections. “They want results and aren’t getting them.” It’s a message as optimistic as Frank’s, but without the satisfying clarity of an Anton or Perlstein. But if it’s right, it implies the “age of populism” has only just begun.

Curt Mills is senior reporter at TAC.

Comments