Poetry and the Past

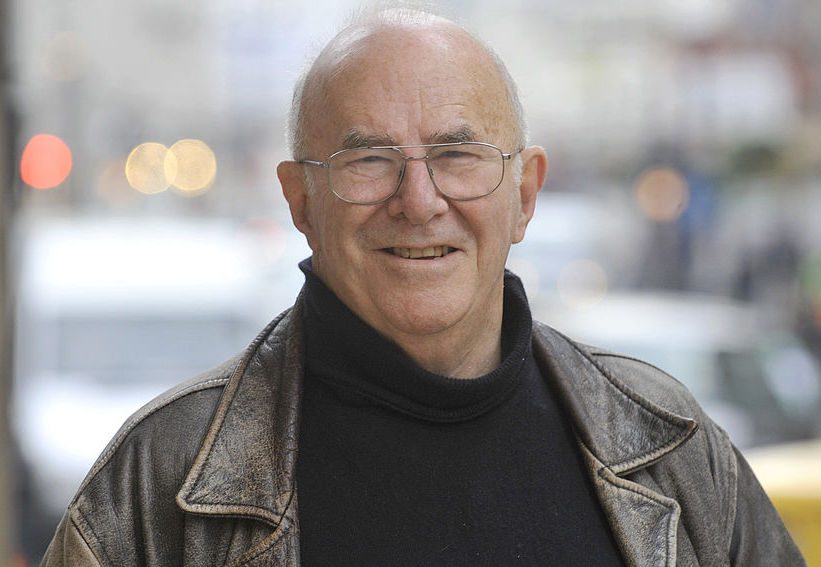

The Guardian publishes an excerpt from Clive James’s posthumous The Fire of Joy: Roughly 80 Poems to Get by Heart and Say Aloud. Lines of poetry did not simply accompany his memories, James writes. It constituted it:

My understanding of what a poem is has been formed over a lifetime by the memory of the poems I love; the poems, or fragments of poems, that got into my head seemingly of their own volition, despite all the contriving powers of my natural idleness to keep them out. I discovered early on that a scrap of language can be like a tune in that respect: it gets into your head no matter what. In fact, I believe, that is the true mark of poetry: you remember it despite yourself.

The Italians have a word for the store of poems you have in your head: a gazofilacio. To the English ear it might sound like an inadvisable amatory practice involving gasoline, but in its original language it actually means a treasure chamber of the mind. The poems I remember are the milestones marking the journey of my life. And unlike paintings, sculptures or passages of great music, they do not outstrip the scope of memory, but are the actual thing, incarnate.

In other news: A big Philip Guston retrospective has been postponed until 2024 over concerns of KKK imagery in his work. Sebastian Smee lambasts the move in The Washington Post: “The catalogue was published. The loans secured. Everything was in place. But four illustrious museums — the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Tate Modern in London — have together decided to postpone, to 2024, a major exhibition devoted to the work of one of America’s most critically acclaimed and influential artists. Why? Because they want to protect the public from having to interpret Philip Guston’s art (which includes cartoon-inspired depictions of figures wearing Ku Klux Klan hoods) for themselves.”

The appeal of Substack: “The platform appeals to some journalists partly because the news media business has been in steady decline . . . Substackers include the former ThinkProgress editor in chief Judd Legum; the climate reporter Emily Atkin; the sportswriter Joe Posnanski; and the Hollywood columnist Richard Rushfield. Two academics — the historian Heather Cox Richardson and the economist Emily Oster — have two of the platform’s most popular newsletters . . . The most popular paid Substack offering is The Dispatch. It was started last year by Steve Hayes, the former editor in chief of The Weekly Standard, along with Jonah Goldberg, a former editor at National Review, and Toby Stock, a former executive at the American Enterprise Institute. A conservative newsletter with more than a dozen employees, The Dispatch has nearly 100,000 subscribers, almost 18,000 paid, and is close to pulling in $2 million in first-year revenue, most of it derived from Substack subscriptions, Mr. Hayes said.”

Saving the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London: “On 2 December 2016, it was announced that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in the East End of London, in existence in some form since the 1570s and on the same site in Whitechapel since the 1740s, and always described as “Britain’s oldest manufacturing company”, would close. It had been sold to a local property developer, Vincent Goldstein, who had in turn sold it on to a New York venture capitalist, Bippy Siegal, who has financial interests in Soho House.”

Bill Buford turns his attention to French cooking: “You can’t say he didn’t warn us. In the final sentence of his previous book, Heat, a joyously gluttonous exploration of Italian gastronomy, Bill Buford announced that he would be crossing the Alps: ‘I have to go to France.’ And here he is, in Dirt, another rollicking, food-stuffed entertainment, determined to unearth, as it were, the secrets of haute cuisine. Lyon, being the gastronomic capital of France, is where he decides to dig in, having uprooted his family (wife, twin toddlers) to facilitate his investigations. Gourmets and gourmands will savour this account of his five-year adventure — and so will students of the author’s curious, compelling character. Famous in literary circles for having revived Granta in the 1980s, and for giving ‘dirty realism’ its name, Buford was for seven years, starting in 1995, the fiction editor of the New Yorker — but literature, it’s now abundantly clear, was just one facet of his career.”

Adam Kirsch reviews Stefano Massini’s dramatic treatment—first in a play, now in a novel—of the Lehman Brothers: “One way of thinking about the Lehmans’ 120-year run is as a lucky convergence of talent and opportunity. Abraham Lehmann, the father of Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer, was a cattle dealer in Bavaria; maybe he too had a genius for commerce, but he had nothing to trade but cows. His sons came to America just when its industrial economy was being built from scratch—largely on the backs of slaves, whose labor in Alabama’s cotton fields was the ultimate basis of the Lehman family’s fortune. (The Lehmans also owned slaves themselves, though Massini barely mentions it.) The young country had a great need for businessmen who knew how to connect producers with consumers, resources with markets, investors with entrepreneurs. For three generations, the Lehmans showed a genius for making such connections. The problem for The Lehman Trilogy is that while Massini recognizes this achievement, he also deeply disapproves of it.”

Mark Rothko’s politics: “During the 1930s and ’40s, Rothko regularly expressed himself politically—he was known to call out publications that printed pro-U.S.S.R. articles, and he has been called an “anarchist” by some historians. One of his most notable political gestures of the era was a protest against an advocacy group known as the American Artists’ Congress. Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and 15 others came to blows with the Artists’ Congress after it issued a motion in support of the U.S.S.R.’s invasion of Finland, which led to increased hostility in the region. Together, Rothko and his colleagues went on to form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, which prized independence above operating as a group.”

Photos: Rhode Island

Get Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments