From Hell’s Ashes, Redemption

In my book Live Not By Lies, I talk about the worst prison of all in the Communist world: Pitesti, in Romania. From the book:

In his life as a political prisoner in communist Romania, the late Lutheran pastor Richard Wurmbrand testified to both truths. The Romania that Soviet troops occupied at the end of World War II was a deeply religious country. After Romanian Stalinists seized dictatorial control in 1947, among the most vicious anti-Christian persecution in the history of Soviet-style communism began.

From 1949 to 1951, the state conducted the “Piteşti Experiment.” The Piteşti prison was established as a factory to reengineer the human soul. Its masters subjected political prisoners, including clergy, to insane methods of torture to utterly destroy them psychologically so they could be remade as fully obedient citizens of the People’s Republic.

Wurmbrand, held captive from 1948 until he was ransomed into Western exile in 1964, was an inmate at Piteşti. In 1966 testimony before a US Senate committee, Wurmbrand spoke of how the communists broke bones, used red-hot irons, and all manner of physical torture. They were also spiritually and psychologically sadistic, almost beyond comprehension. Wurmbrand told the story of a young Christian prisoner in Piteşti who was tied to a cross for days. Twice daily, the cross bearing the man was laid flat on the floor, and one hundred other inmates were forced by guards to urinate and defecate on him.

Then the cross was erected again and the Communists, swearing and mocking, “Look your Christ, look your Christ, how beautiful he is, adore him, kneel before him, how fine he smells, your Christ.” And then the Sunday morning came and a Catholic priest, an acquaintance of mine, has been put to the belt, in the dirt of a cell with 100 prisoners, a plate with excrements, and one with urine was given to him and he was obliged to say the holy mass upon these elements, and he did it.

Wurmbrand asked the priest how he could consent to commit such sacrilege. The Catholic priest was “half-mad,” Wurmbrand recalled, and begged him to show mercy. All the other prisoners were beaten until they accepted this profane communion while the communist prison guards taunted them.

Wurmbrand told the American lawmakers:

I am a very insignificant and a very little man. I have been in prison among the weak ones and the little ones, but I speak for a suffering country and for a suffering church and for the heroes and the saints of the 20th century; we have had such saints in our prison to which I did not dare to lift my eyes.

After his release, Pastor Wurmbrand, who died in 2001, devoted the rest of his life to speaking out for persecuted Christians. “Not all of us are called to die a martyr’s death,” he wrote, “but all of us are called to have the same spirit of self-sacrifice and love to the very end as these martyrs had.”

Accompanying other persecuted people in their suffering can lead us to deep repentance and spiritual strength. One of Wurmbrand’s fellow Piteşti prisoners was George Calciu, an Orthodox Christian medical student who was eventually ordained a priest. In 1985, he was sent into exile in the United States, where he served at a northern Virginia parish until his death in 2006.

In a lengthy 1996 interview, Father George told about his encounter with a fellow prisoner named Constantine Oprisan. They met when Calciu was transferred from Piteşti to Jilava, a prison that was built entirely underground. The communists put four prisoners in each cell. In his cell was a man named Constantine Oprisan, who was deathly ill with tuberculosis. From their first day in captivity there, Oprisan coughed up fluid in his lungs.

The man was suffocating. Perhaps a whole liter of phlegm and blood came up, and my stomach became upset. I was ready to vomit. Constantine Oprisan noticed this and said to me, “Forgive me.” I was so ashamed! Since I was a student in medicine, I decided then to take care of him . . . and told the others that I would take care of Constantine Oprisan. He was not able to move, and I did everything for him. I put him on the bucket to urinate. I washed his body. I fed him. We had a bowl for food. I took this bowl and put it in front of his mouth.

Constantine Oprisan—“he was like a saint,” Father George said—was so weak that he could barely talk. But every word he said to his cellmates was about Christ. Hearing him say his daily prayers had a profound effect on the other three men, as did simply looking at the “flood of love in his face.”

Constantine Oprisan was a physical wreck because he had been so badly tortured in Piteşti for three years, reported Father George. Yet he would not curse his torturers and spent his days in prayer.

All the while, we did not realize how important Constantine Oprisan was for us. He was the justification of our life in this cell. Over the course of a year, he became weaker and weaker. We felt that he had finished his time here and would die.

After he died every one of us felt that something in us had died. We understood that, sick as he was and in our care like a child, he had been the pillar of our life in the cell.

After the cellmates washed his body and prepared it for burial, they alerted the guards that Constantine Oprisan was dead. The guards led the men out of the windowless cell for the first time in a year. Then the guard ordered Calciu and another man to take the body outside and bury it. Constantine Oprisan was nothing but skin and bones; his muscle tissue had wasted away. For some reason, the skin pulled tight over his emaciated skeleton had turned yellow.

My friend took a flower and put it on his chest—a blue flower. The guard started to cry out to us and forced us to go back into the cell. Before we went into the cell, we turned around and looked at Constantine Oprisan—his yellow body and this blue flower. This is the image that I have kept in my memory—the body of Constantine Oprisan completely emaciated and the blue flower on his chest.

Looking back on that drama nearly a half century later, Father George said that nursing the helpless Constantine Oprisan in the final year of his life revealed to him “the light of God.”

When I took care of Constantine Oprisan in the cell, I was very happy. I was very happy because I felt his spirituality penetrating my soul. I learned from him to be good, to forgive, not to curse your torturer, not to consider anything of this world to be a treasure for you. In fact, he was living on another level. Only his body was with us—and his love. Can you imagine? We were in a cell without windows, without air, humid, filthy—yet we had moments of happiness that we never reached in freedom. I cannot explain it.

In terms of sacramental theology, a mystery is a truth that cannot be explained, only accepted. The long death of Constantine Oprisan, which gave spiritual life to those who helped him bear his suffering, is just such a mystery. The stricken prisoner was dying, but because he had already died to himself for Christ’s sake, he was able to be an icon to the others—a window into eternity through which the divine light passed to illuminate the other men in that dark, filthy cell.

When I give talks about the book — like I did today to a luncheon group at the Greek Orthodox cathedral in Birmingham, Alabama — I talk about how as Christians, we know that if we suffer faithfully, uniting our agonies to Christ’s, that God will use them for our redemption, and the redemption of the world, even if we do not live to see it.

I was able to share with my lunch audience this news from Romania, sent to me this morning by Frederica Mathewes-Green:

Piteşti Prison of communist Romania was home to unspeakable horrors, where thousands suffered for their faith in Christ and political dissension.

Now, the former penal facility is set to become the site of a future Orthodox church in honor of all who suffered there.

The foundation stone for the future church was placed and consecrated on Monday by His Eminence Archbishop Calinic of Argeș and Muscel. The necessary arrangements for building a new church were worked out by Fr. Cozmin Ionuț Miloiu, who currently serves in the chapel at the prison building, reports the Basilica News Agency.

Glory to God! The Communists made that piece of earth into Hell, but now they are dead, and a church will rise on the site! There is reason to hope!

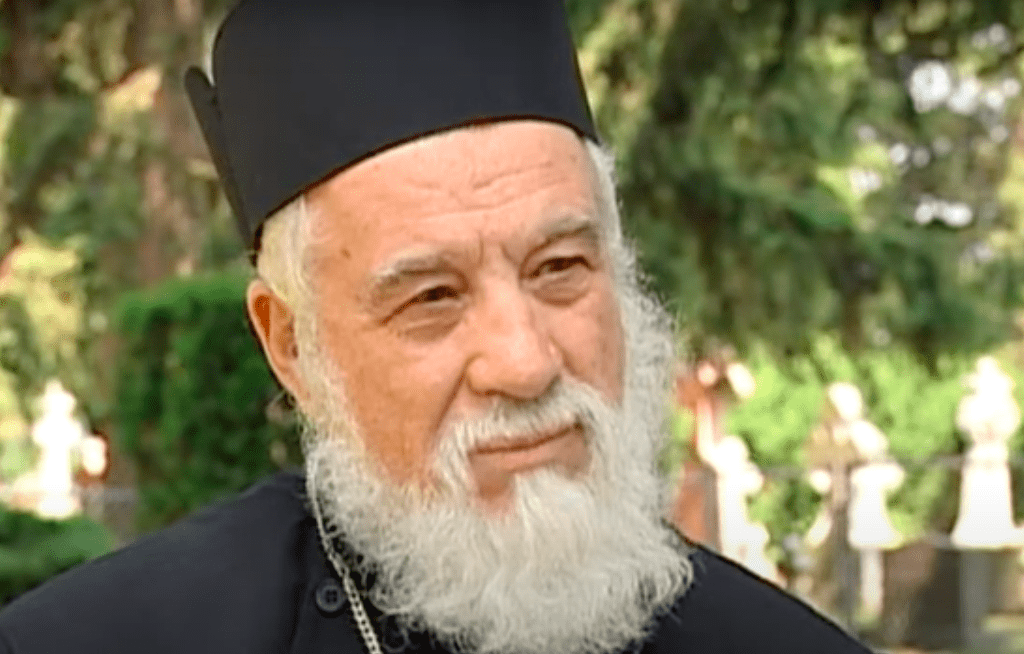

Watch the 34-minute documentary about Pitesti, featuring the late Fathers Roman Braga and George Calciu, Orthodox priests who suffered there:

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.