No, I Won’t Check My Privilege

“Check your privilege!” It happened again last week. I was speaking about feminism to a large and vocal audience and my views were, rightly, coming under scrutiny. I was accused of criticizing #MeToo but ignoring domestic violence, using pay gap and employment data selectively, and focusing exclusively on the experiences of middle-class women. It was a robust and stimulating debate. Then, just before the end, came the now-hackneyed retort: privilege! My criticisms of feminism were, I was told, simply a reflection of my own privilege, and I should shut up and listen to those with less of it.

Privilege-checking has its roots in academia (of course) but when it first emerged three decades ago it was a minority pursuit. Back in 1988, Peggy McIntosh, professor of women’s studies, wrote a paper called “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies.” In it, she helped rehabilitate the then-unfashionable view that men and women, white people and black people, are born differently and as a result experience the world in different ways.

McIntosh’s work preempted later thinking in critical race theory and gender studies; it lent weight to the idea that people can be categorized according to gender, race, and sexuality, and that each group membership confers particular advantages or disadvantages. Intersectionality became the word of choice to describe how individuals, who might belong to several overlapping groups, faced multiple layers of interconnected discrimination.

Privilege-checking took off around 2013 when it moved from academia to social media. The idea that people gain special advantages—privilege—based on the groups they belong to rapidly became a convenient means of keeping an intersectional score card. In the minds of those keeping count, privilege is something that must, like original sin, be acknowledged and atoned for. Over the past five years, calls on anyone making an argument that challenges the intersectional orthodoxy to check their privilege have become ubiquitous. It’s the go-to response of those determined to stake a claim to the moral high ground but unable to formulate a coherent argument.

Calling on someone to check his privilege is a cheap form of ad hominem attack. It focuses on the person rather than what they are saying; it asks others to make judgments based on who an individual is rather than the strength of his argument. My response to having my apparent privilege pointed out was outrage. How dare someone with no knowledge of my personal history make such sweeping assumptions? How dare they overlook all my many wonderful arguments and focus instead on my biology, something I have no control over?

It turns out it’s not all about me. The demand for privilege-checking tells us far more about the accuser than the accused because those invoking the phrase draw attention to themselves as much as to their target. They do this by demanding that everyone pay homage to their more finely tuned morality and superior knowledge of intersectional hierarchies. As such, “check your privilege” is the perfect retort for today’s many virtue-signalers who seek to lead their chosen communities of the disadvantaged.

As privilege-checking has become mainstream it’s been interpreted more broadly and more literally. In 2014, McIntosh revisited the term and, to her original focus on gender and “whiteness,” she added: “one’s place in the birth order, or your body type, or your athletic abilities, or your relationship to written and spoken words, or your parents’ places of origin, or your parents’ relationship to education and to English, or what is projected onto your religious or ethnic background.” Elsewhere, we’re told about short person privilege and hair privilege.

Calls to check your privilege are now being promoted on campuses by diversity officers rather than academics. Posters inform students that if they can use public bathrooms without “stares, fear or anxiety,” they have “cisgender privilege.” Or that if they can expect time off from work to celebrate their religious holidays, they have “Christian privilege.” Lists with boxes to tick help students identify their own privilege ratings.

Back in 1988, the concept of privilege did little to challenge racism or sexism. It reinvented discrimination as a fixed condition rooted within the biological differences between individuals rather than a social problem. The solutions proposed were therapeutic rather than political. Dominant groups were told to shut up and listen; underrepresented groups had their suffering affirmed. As privilege comes to be understood ever more broadly, as it encompasses talents that can be honed through effort such as athletic ability or random features about a person like birth order that no one could guess unless told, the whole idea of discrimination has become trivialized.

By far the biggest determinant of privilege is social class. Intersectionalists, however, have little to say about this. Social class, far more than birth order, body shape, or sexuality, far more even than race or sex, determines a person’s life chances. Yet social class also pulls the rug on the whole intersectional framework: working-class women have far more in common with working class men than they do with their elite sisters. But for the privilege checkers, social class is just one factor among many. And as a cultural rather than economic concern, it becomes fixed and determining, never something people can aspire to leave behind.

The whole idea that privilege can be tallied and each person awarded merits and demerits based on gender, skin color, sexuality, hair type, or body shape is nonsense. It’s racist and sexist in the way it asks us to pre-judge people. It closes down debate: some are told to shut up while others are awarded compensatory speaking points. Discussion stops being about facts or even contested opinions and instead becomes a trading of competing claims to victimhood. In fact, if every view is predetermined by our inherent privilege then there is no need to discuss or debate at all. Our discussions can never move beyond the accidents of our birth.

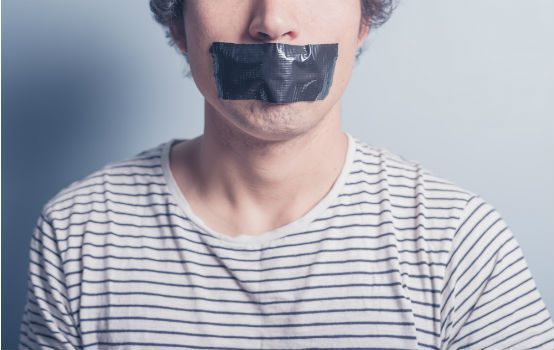

The cry of “Check your privilege!” is a well-worn rhetorical trick that manages simultaneously to undermine an argument, detract from the speaker, and shut down further discussion. It’s long past its sell-by date and should be put out of its misery entirely.

Joanna Williams is the author of Women vs Feminism: Why We All Need Liberating from the Gender Wars.