Wokeness As Bourgeois Bolshevism

I don’t know what you’ll be doing tonight, but I’ll be watching Mr. Jones, a new film out on Netflix after its theatrical release was botched by Covid-19. It’s about a brave Welsh journalist in the 1930s Soviet Union who faced down Stalin and his lackey Walter Duranty, the New York Times‘s Moscow correspondent, and reported honestly on the Holodomor — the massive famine that Stalin engineered during the Great Depression. It cost the lives up to twelve million Ukrainians, whose grain was stolen from them and sold abroad.

In this powerful endorsement of the movie by Fran X. Maier in First Things, we learn who Mr. Jones was:

Welshman Gareth Jones was a young Russian Studies graduate of Cambridge and a former secretary to British Prime Minister Lloyd George. Stringing for the same Manchester Guardian as Muggeridge, he eluded Soviet press controls and spent three weeks on his own, walking through the hellish conditions of a starvation-ravaged Ukraine. Then he wrote about it in the spring of 1933, confirming and compounding the impact of Muggeridge’s recent work. Walter Duranty led the ferocious, Soviet-prodded attack on Jones’s credibility. He also bullied most other Moscow-based Western journalists—to their enduring disgrace—into doing the same, lest they lose their visas. Jones, however, had a spine. He did not back off. He continued writing and speaking about the famine in Ukraine with lasting effect, until his death under suspicious circumstances two years later.

All of which is interesting history. But why return to it now?

Last month, on June 19, Samuel Goldwyn Films released to an American audience the British/Polish/Ukrainian production Mr. Jones, loosely based on the story of Gareth Jones and his coverage of the Holodomor. The words “must see” are grotesquely overused in movie reviews, but in this case, they are apt. From a compelling James Norton in the title role, to the superb period atmosphere created by Andrea Chalupa (writer) and Agnieszka Holland (director), to a brilliant, understated performance by Peter Sarsgaard as Duranty, Mr. Jones is a riveting experience. And a relevant one. At a time when lying, bullying, and violence seem to be making a comeback in the vestments of progress, equality, and justice, Mr. Jones is a useful lesson in consequences. It’s an opportunity to watch and learn.

Read it all. As Maier points out, Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize was never rescinded. The Pulitzer board, as you know, awarded another Times writer, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Pulitzer this year for her falsification of history in the service of leftist ideology. It’s comforting, perhaps, to learn that some things never change, either with the Times, or with the Pulitzer board.

Meanwhile, English political philosopher and columnist John Gray also weighs in powerfully on the side of Mr. Jones. He writes that the film illuminates what the woke movement shares with Communism. Excerpts:

Gareth Jones’s achievement, which is well captured in James Norton’s powerfully expressive performance, was to discover the answer to a question that hardly anyone wanted to ask. Western resistance to his inquiry, which cost Jones his job and possibly his life, was partly a result of the belief among western intellectuals that the Soviet state was the last best hope of humankind, which must be defended at any cost.

Many will argue that in a time when fascism was on the rise, this was an understandable response. But Jones had no illusions about the dangers of Nazism; he was one of the first western journalists to fly with Hitler after he came to power, and secured an interview with Goebbels that left him in no doubt of the deadly threat posed by the Nazi regime. Even so, he refused to condone or pass over in silence the crimes of the Soviet state.

At this point we reach the nub of the film. A scene features Jones in conversation with George Orwell, arguing that the truth must be told. Orwell responds with a question of his own: if the Soviet regime is as bad as Jones claims, what hope is there? There is no evidence that any such encounter ever occurred, but in the context of the film it is an effective device. The choice Jones faced was between hope and truth, and Jones — like Orwell himself in Animal Farm, published in August 1945 — chose truth.

More:

Yet it is doubtful whether this or any similar film will have much impact in the current climate of opinion. In the 1930s the western Left resisted the facts regarding Soviet crimes because it undermined the hopes of a new society. Today the woke movement questions the very idea of truth. Intermixed with millenarian frenzy and American Puritanism, Maoist mob rule and hyper-liberal culture war, there is a strand that echoes Duranty’s crypto-Nietzschean philosophy.

Read it all, especially Gray’s conclusion. I’m not going to reveal it — read the piece for yourself — but I will say that I agree with it, with the qualification that a hell of a lot of real destruction can take place before everybody else discovers what Gray already knows. It is for the cause of helping good and decent people to endure this coming destruction, and to suffer for truth, no matter what the totalitarians throw at them, that I have written Live Not By Lies. A passage that you have not yet seen:

Mária Komáromi teaches in a Catholic school in Budapest. She and her late husband, János, were religious dissidents under the communist regime, and bore many burdens to keep the faith alive.

“You have to suffer for the truth because that’s what makes you authentic. That’s what makes that truth credible. If I’m not willing to suffer, my truth might as well be nothing more than an ideology,” she tells me.

Komáromi elaborates further:

Suffering is a part of every human’s life. We don’t know why we suffer. But your suffering is like a seal. If you put that seal on your actions, interestingly enough, people start to wonder about your truth—that maybe you are right about God. In one sense, it’s a mystery, because the Evil One wants to persuade us that there is a life without suffering. First you have to live through it, and then you try to pass on the value of suffering, because suffering has a value.

Suffering for truth has dignity and weight; accepting lies because they make you more comfortable is contemptible. The fact that public intellectuals like Fran Maier and John Gray recognize the totalitarianism within wokeness, and how wokeness in power compels everyone to affirm lies, tells me that neither I, nor the survivors of Soviet communism who talked to me for the book, are being alarmist.

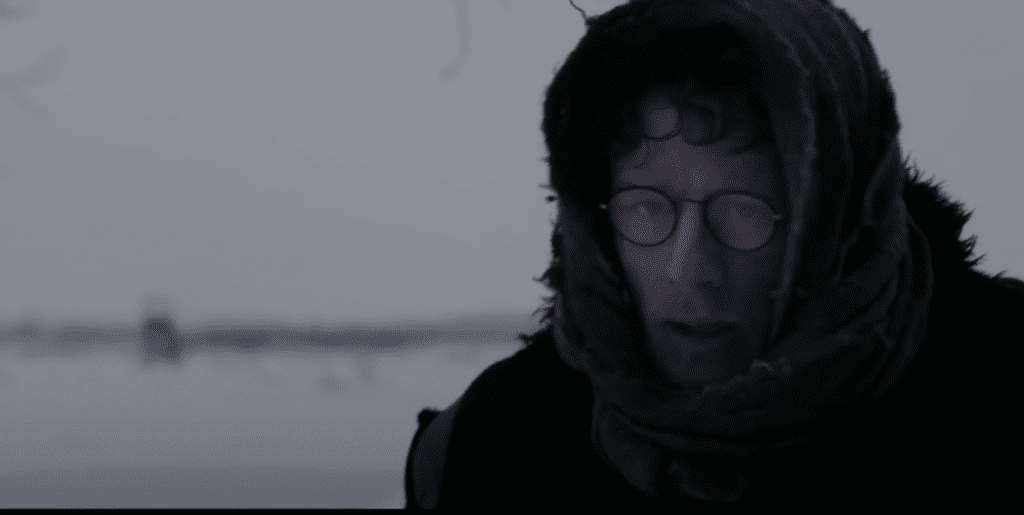

Here’s the trailer for Mr. Jones. You know, I might not get to it tonight, if my kids can’t watch it with me. I want them to see Gareth Jones, and to understand that they are called to be like him.

UPDATE: Ah, rats, it appears not to be on Netflix in the US, but in the UK. But you can rent it in the US for $4.99 on Amazon streaming. I will!

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.