Let’s Get Ready To Read Dante’s Paradiso

I’ll start blogging Dante’s Paradiso on May 1 — the anniversary of the date that child Dante met child Beatrice at a May Day party at her father’s house. I’m going to do the blogging a bit differently this time. For Purgatorio, I blogged on one canto per day, to make sure we got through it during Lent. It was a rigorous schedule to keep, both for me as a writer and many of you as readers. Paradiso is an even denser work, so I don’t want to push myself or you too fast. So, I’m not going to stick to a fixed schedule. And this time, I will publish at the end of each day’s reflection links to everything that came before, so you can jump right in easily, even if you’ve missed a day or two.

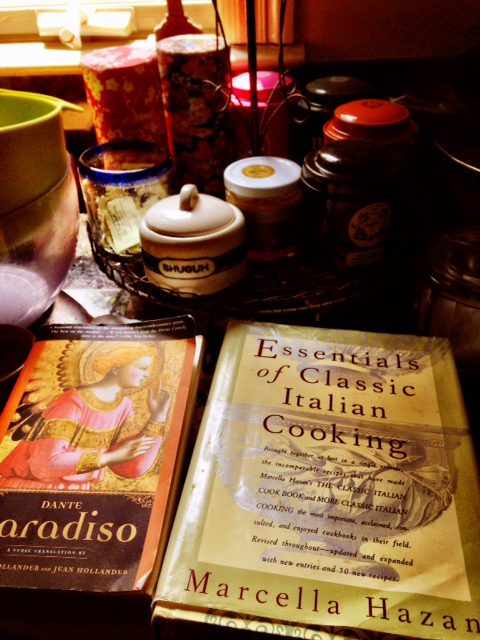

Now is a good time to buy your copy of Paradiso, if you haven’t already. As ever, I recommend the Hollanders’ translation, or Mark Musa’s, in the Penguin Classics edition (not The Portable Dante; it has few notes). Anthony Esolen’s is also quite good, but more poetic and less literal than the others. Here’s a link to a page on Amazon.com, in which a reader, Jordan Poss, compares translations; it may be helpful to you. His favorite is Esolen’s, but he’s also quite fond of the Hollanders’ version, and has good things to say about Musa’s as well.

Here’s a review essay in The New Yorker from 2007, in which Joan Acocella assessed the new (back then) Robert and Jean Hollander translation of Paradiso. Acocella rightly says that Paradiso is the most straightforwardly theological of the Commedia‘s three canticles, and is for the modern reader the most difficult. Plus, there’s a basic storytelling problem Dante must face: in the Inferno and the Purgatorio, the characters Dante meets all exist in tension. The damned are raging against their fates, and the penitents suffer, but they endure their suffering because it is changing them, and they know they are going to be reunited eventually with God. In Paradise, though, the characters are fulfilled and complete. There is no contradiction within them, so the dramatic tension is all but non-existent. Ergo, Paradiso is the most straightforwardly catechetical of the canticles, and it poses the greatest challenge for Dante the poet: how on earth does he keep us interested all the way to the end?

He does do this, but it requires more work on our part than the previous two canticles. I’ll be going through this work with you. You mustn’t be under the impression, though, that this is going to be homework, or an eat-your-spinach experience. Acocella writes:

Nevertheless, people should read the Paradiso. How can they read the first two-thirds of the story and not the end? Furthermore, it is not a waste of time, whatever our religious inclinations, to learn something about Christianity at its most systematized. For many centuries, European culture was rooted in the Scholastic synthesis. No one can understand Europe’s past without it.

There are literary reasons, too, for reading the Paradiso. Of the bliss that is Heaven, Dante makes sublime images: flames and roses, rivers and rainbows. Heaven’s light is seen “sparking everywhere, / like liquid iron flowing from the fire.” Created things move “toward different harbors / upon the vastness of the sea of being.” What most modern readers love Dante for, however, is not his sublimity but its opposite—terseness, earthiness, vigor, the qualities Croce praised him for—and in Paradise we still see this side of him. At one point, Dante says that Beatrice’s smile would make a man happy even if he were on fire. Elsewhere, a soul counsels the pilgrim always to tell the truth, and if people don’t like it, “let him who itches scratch.”

The major source of concreteness, however, is the metaphors, and the best example is the most celebrated one. When he wrote the Divine Comedy, Dante, because his political party had been routed, was in exile from his native city, Florence, and was living with friends, sometimes in Verona, sometimes in Romagna or Ravenna. The Comedy takes place in 1300, two years before he was expelled from Florence, but in Heaven his great-great-grandfather Cacciaguida predicts his banishment: he will learn how salty is another man’s bread, Cacciaguida says, and how hard it is to go up and down another man’s staircase. What could be simpler or more concrete than this—a staircase that seems long, bread that tastes peculiar? (Hollander informs us that, to this day, Florentine bakers make their bread without salt.) Critics exclaim over how much of our world there is in the supposedly otherworldly Comedy. In Paradise, there’s less of it, but it’s still there. Snow falls; the sun burns off the morning mist. Clocks chime (the first reference in European literature to mechanical timepieces). Babies nurse; pigs and dogs do what they do. A pilgrim arrives at a shrine—the place he has vowed to travel to—and greedily stares here and there in the church, knowing that the minute he gets home his neighbors are going to want to know everything. This last is more than an image; it’s a little story.

You know what I’m going to do to celebrate May Day, the anniversary of Dante’s and Beatrice’s meeting, and the start of our pilgrimage, yours and mine, through Paradiso? I’m going to make a little Tuscan meal of some sort, and open a bottle of Tuscan wine. If any of you care to join me, virtually, please send in views from your Dante and Beatrice table.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.