Joe Biden is Not a Nice Guy

“Joe is a nice guy.”

“Joe is a decent man.”

You have probably heard variations on these arguments put forward by friends who want you to vote for Biden. Whether they get into the grubby details or not, we know what they’re saying: he hasn’t been married three times, and he wasn’t involved with a porn actress. Even if Biden is going to bring Antifa supporters and reparations proponents and open border advocates and lots of other crazed America-haters into the White House, he’s fundamentally honorable.

The problem with this story is that it doesn’t jibe with Biden’s history. And given the stakes, it’s worth taking a moment to review that.

For the moment let’s hold off with the rape accusation that’s been leveled against him by a former aide—at least as credible as those against Brett Kavanaugh—or the questions about his declining mental condition. Instead, why don’t we examine the mostly forgotten details surrounding the reasons why Biden had to exit from his first Presidential campaign.

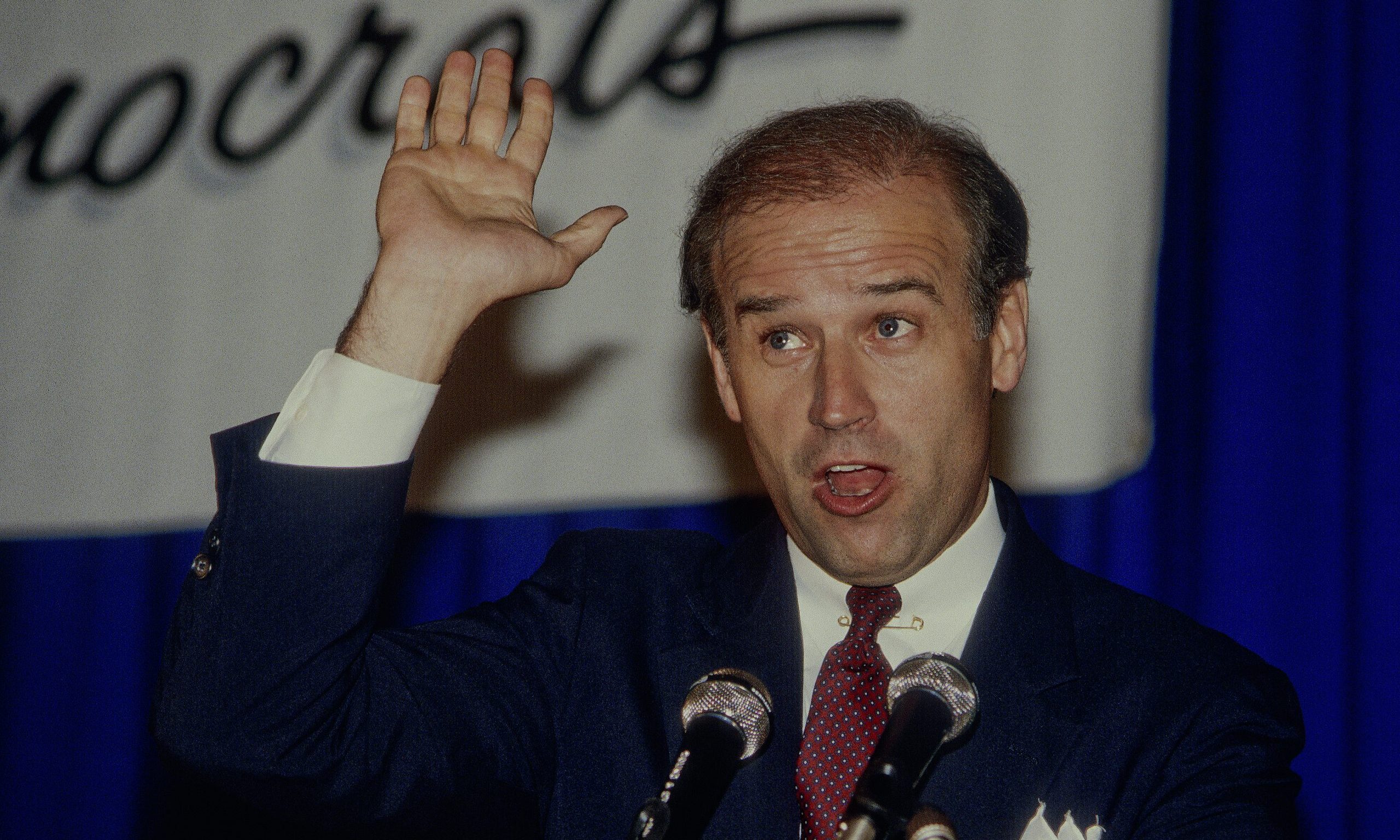

Biden will turn 78 in November, and he was first elected to the Senate in 1972. That was before the Watergate investigations and the end of the Vietnam War. So he was actually a political veteran when he announced his first Presidential run in 1987. At that point he was in his mid-40s and in the midst of his third term in the Senate. He was not a political novice, though he was already combing his hair over to hide his increasing baldness. Many people who were alive and old enough to read at the time likely remember that he had to leave that race because of a disgraceful admission: he had giv en a speech as his own which was actually an old stump address of British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock. Probably they assume that an aide had given him the speech and that he had not known that it was plagiarized.

This is false.

In fact, Biden had given the speech many times, and he had even told people on at least one occasion that it was a Kinnock speech. More remarkably, in it he had claimed that his family were ordinary coal miners, regular folk who had been unfairly disadvantaged by economic circumstances. But Biden’s background in Pennsylvania’s anthracite country was monied. His father’s family hadn’t been miners but rather oil company owners. Nonetheless, in the speech Biden suggested that his forebears had been so destitute that they had only rarely come up from underground to see the light of day and play an occasional game of football. In Kinnock’s case that had referred to soccer. While Biden had played football—American football—it was at a private Catholic school that his parents had paid to send him to. The speech was about how some people wrongly start out at the bottom, and he had used it to mislead people into thinking that he was one of them.

Nor was this the only talk from which Biden cribbed. On repeated occasions he used pieces from effective speeches he had heard given before by other Democrats he admired, including John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey.

He had commenced the race with an announcement address in which he had spoken about the importance of character and values. Attacking Reagan, he had affirmatively declared that, “We must rekindle the fire of idealism in our society, for nothing suffocates the promise of America more than unbounded cynicism and indifference.” But plagiarism and lying were not new to Biden.

During the race, reporters discovered that Biden had failed a course at Syracuse Law School because he had stolen a paper from a Fordham Law Review article. Five pages of the paper were taken word for word. Showing impressive chutzpah, Biden said that this was unintentional. Biden also claimed that he had graduated in the top half of his law school and had received a full scholarship. In fact, his scholarship was only partial, and he had graduated 76th out of a class of 85 students.

Biden also spoke frequently during the race of his experiences marching for equality during the Civil Rights era. This, too, was a fabrication. And when confronted about these lies, he challenged the reporters who asked him about them, saying that he had done his part by running for office, asking them what they had done for Civil Rights.

In addition, Biden had managed to avoid service in Vietnam by claiming that he suffered from asthma—even though he had been a star halfback and wide receiver in high school.

Nor did all of these revelations shame him into leaving the race. Instead, he held a press conference in which he insisted that he was going to continue with his campaign, and he only dropped out a week later when it became clear that his persistent lying had defined his candidacy and that it was affecting fundraising.

That was of paramount concern. While Biden was not doing well in polls or with crowds, until that point he had excelled at raising money. This was so much true that he had more funds on hand than the eventual nominee, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, and even more than Dick Gephardt, who was Chair of the House Democratic Caucus and seemingly in an ideal position to hit up lobbyists for funds. In fact, he had the most funds of any Democratic candidate.

Simply put, Biden was good at scheming and talking out of both sides of his mouth. He could tell industry reps and trade groups that he was their pal, and then go before crowds of liberal activists and rap about his non-existent days of marching for racial justice and his concern for environmental activism. He was a fraud and a phony, and his exit from the race was compelled not by any sense of shame but by the cumulative effect of reporting by journalists who bothered to dig into his background and his record.

The collapse of his Presidential campaign and the many ugly revelations necessarily affected his reputation and his popularity, and in the aftermath he was desperate for an issue that might improve his chances at re-election to the Senate and re-establish his stature nationally among Democrats.

Biden soon found a political instrument by which to revive his career in Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Bork’s nomination was in some respects surprising. Reagan had not nominated him in expectation that he would serve as a reliable conservative voice for decades afterwards. After all, Bork was already 59 and considerably overweight. Instead, he had been chosen because many regarded him as America’s foremost judicial theorist, the most influential and respected such figure since the days of Learned Hand and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Bork was then serving as a federal judge, and in that role he had displayed not only his learning but moderation. Going further back, a legal analysis had demonstrated that in his time working in the Solicitor General’s office under Richard Nixon that Bork had been as liberal as Thurgood Marshall had been on the Court in the Johnson administration.

But in helping to lead the fight against Bork, Biden would help to create a new word. We know it in its infinitive verb form: to Bork. This means to mount a misleading, intellectually dishonest campaign meant to defame a candidate. This was less than two months after Biden had left the Presidential race.

We do know that among all of these incidents we must file the accusation of rape made by his former aide Tara Reade.

I confess that I find certain aspects of her claims to be inconsistent. In any event, the specific charge of rape falls into the category of he said/she said accusation, and, as this kind of charge can be made against any public figure, it may be unfair to grant it too much credit, notwithstanding the fact that it has been made by a former staffer who appears to have no personal motive against him.

Regardless, the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s—the period of Biden’s first Presidential campaign and of Reade’s employment in his Senate office—show him to be a shabby and disreputable man. It is not an exaggeration to say that it presents the picture of a scoundrel.

The large amount of plastic surgery he’s had in recent years is hard to miss. It appears to be the reason why you can barely see his eyes now. Of course, there’s an old adage that the eyes are windows to the soul. That part of him is well and properly hidden.

Jonathan Leaf is a playwright and journalist living in New York.